Published on April 5, 2013

The challenges of rebuilding an early era aircraft are extraordinary. The few that remain in flying condition today are rarely flown at all. Some builders have built “new” copies of the older planes based on the original plans. Even then, there are challenges — for instance, where does one find a ready-to-fly Anzani three cylinder engine from 1911? The late Cole Palin of Rheinbeck used to collect old airplane engines both at his New York hangar and at his winter hangar at the airport of Boca Raton, Florida. If he found a servicable Hispano-Suiza 8 BEc, water cooled V-8, 235 hp engine, then he would store it until he was ready to build a SPAD S XIII around the engine, as but one example. Today, another famous builder resides in Sweden, creating new “old” aeroplanes in much the same way — his name is Mikhael Karlsson and, among the many planes he has built is a Blériot.

Today’s feature highlights a fascinating rebuild of a Blériot monoplane that was flown by none other than Mr. Vivian Hewitt of Great Britain. His experience of rebuilding the plane is particularly interesting for one reason — the rebuild itself was accomplished not today, but exactly 100 years ago by Mr. Hewitt himself.

The Rebuild

Precisely 100 years ago today in aviation history, the Royal Aero Club in England ran an interview with Mr. Hewitt about his efforts to rebuild his tired Blériot. At the time, other types were overtaking the venerable Blériot in performance and reliability, but there was something about the plane that no doubt drew him to update and rebuild the plane. In any case, perhaps Mr. Hewitt had market motives to do the rebuild, after all, he had just opened up an aeroplane shop specializing in such work at Foryd, Abergele, N. Wales. His shop included a power lathe, shaper, drill and grindstone, and a large assortment of tools. He had three mechanics are employed and, as Flight pointed out, “Electric light is produced on the spot, there are arrangements for re-magnetising magnetos, and a nickel-plating plant.” Pretty advanced stuff….

The interview began simply with a description of Mr. Hewitt’s work in his shop:

After his trip across the Irish Sea, Mr. Hewitt decided to completely dismantle his Blériot monoplane and rebuild it, incorporating during the process some ideas of his own. The result is seen in the accompanying photos, and Mr. Hewitt tells us that two of his mechanics have been engaged on the work during the past five months. The only original part of the framework of the machine is the landing chassis, the engine, and the four longitudinal members of the fuselage. Complete, the machine, in its latest form weighs about 35 lbs. more than it did originally.

Regarding the alterations which have been carried out, Mr. Hewitt says: — “The wings each weigh 10 lbs. more than Bleriot’s wings, and are fitted with a wooden leading edge instead of a piece of aluminium bent round. The ribs are all slightly thicker, and the wings altogether stronger all round. The front spar and rear spar are fitted with four plates each instead of two. It is impossible for air to enter the wing, where the plates come through the fabric, as small pieces of wood are fastened to the spars inside the wings and the fabric is nailed to these. A piece of cane runs along each rib over the fabric instead of only as far as the radius of the propeller. Round the tube that the front spar of the wings fits into extra steel brackets have been fitted, thus strengthening it up.”

Technical Details

Mr. Hewitt continued with a technical description of the modifications he was undertaking, no doubt hoping to improve the plane:

“The cabane is slightly thicker gauge steel tube, and there is no piece of wood let in at the top. Instead the whole is braced together, having previously been cut out of steel and carefully fitted. There are four steel warping wheels for the top bracing wires to work on, and the bolt for the four front wires is half as thick again as in the original machine. The cabane is stayed across near the bottom to take any strain off the fuselage. It is braced from the top to the fuselage by eight wires instead of four.

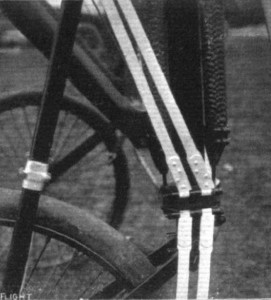

“The ribbons for staying the underside of the wings are belled out at the ends where tin steel clips are riveted to them, thus obtaining uniform strength throughout. There are four ribbons to each wing. The bottom planche has a strong steel ribbon, suitably drilled out, for lightness, running from one end to the other, and connected to the ribbon brackets. The planche is made of hickory.

Yet More Details

Mr. Hewitt continued with even more attention to the modifications he had undertaken, and to illustrate his points, he provided photos — all of which we have republished here, throughout this article.

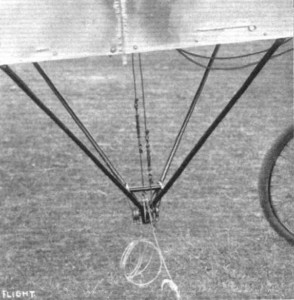

“The bottom cabane which takes the warping gear is braced together by cross tubes, as can be seen in the photograph. There are also two steel ribbons from one side to the other of the fuselage where the warping cabane bolts on, thus taking up the tendency to push the fuselage members out when climbing. The warping bracket, which was originally aluminium, is now steel machined out of the solid and brazed into the tubes. There are four warping wires instead of two to the wings, and these pass round steel wheels. The wires from the cloche to the warping arm are double the thickness of those originally used.

“The cloche has four steel arms running from the top to the bottom of the bell to which the control wires are attached, so that even should they (the control wires) break from the aluminium the steel arms still hold them. As the arms are all cut out of a single piece of sheet steel, and the whole slipped over the cloche, it is impossible for these to come adrift.

Complying with Regulations?

At this point, one realizes just how wide a latitude the aircraft owners of that age truly had — they could modify, trim, lighten, strengthen or change any part of their aeroplanes based on their own best judgment and with little or no official review. Of course, if they got it wrong, they crashed. Clearly, there was an inherent tendency to try to get it right — a trait that remains among today’s EXPERIMENTAL category airplane builders. Here are a few more of the modifications Mr. Hewitt completed on the Blériot:

“The fuselage has had light steel plates fitted between it and the distance pieces of the fuselage, thereby making the cross bracing less liable to give, and also preventing the distance pieces from splitting at the bottom. The floor has had four pieces of wood screwed on the underneath side, making it less liable to split.

“The elevating tail has stronger tubes to stay it to the fuselage, and the fuselage is stayed from one side to the other where these are bolted on, thus taking the strain off the cross-bracing to a certain extent. The body is composed of aluminium, left bright and finished off with copper rivets. It tapers off behind the pilot’s seat to a tail. Doors are fitted on each side of it for cleaning the tanks, &c, and the shield over the engine leads into it, as can be seen clearly in the photograph. In every direction accessibility has been aimed at, and it is interesting to note that the doors and engine shields can be taken off in two minutes. In the photographs the aluminium looks as if it were dented. This is not so, as it is only the reflection of the sun.

“A release clip is fitted to the skid and stayed to the fuselage. The ribbons are painted white, and also all the wires. The rest of the machine is painted a deep fast red, which shows up very well with the aluminium. All the wires were boiled in soda and water, in case of rust, and before being painted were coated with two coats of red lead.”

So ended the description of the modifications that Mr. Hewitt prepared at his workshop in Wales. For today’s rare Blériot builder, some of these items might be illuminating and helpful as one would go about building or rebuilding their own old aeroplane. On the other hand, it does make clear that there were few guidelines in the old days — so today’s builder shouldn’t be blamed for “bending the rules” a bit. So if you can’t find an Anzani or a Gnome, why not use something a little more modern and reliable?

Ultimately, Mr. Hewitt’s interview serves to demonstrate that it really took a lot of skill and knowledge to build and fly these old aeroplanes. For sure, very few of today’s EXPERIMENTAL home-builders would want to tackle a project like Mr. Hewitt’s Blériot — oh, but to imagine it….

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What happened to Mr. Hewitt’s rebuilt Blériot? Why was his Blériot important in history?

From 2006 to 2010, I had a similar project here in Brazil to build a new Demoiselle from Santos-Dumont. I finished the design phase after a five years plus historical and technical research, but unfortunately I could not get funding to continue and build the replica.

Nice to read this. An inspiration to the project I am doing right now. Building a replica of the Bleriot XI:

http://bleriotxi.com/

Please assist in locating a Bleriot XI and owner willing to tour Florida in the 2016 spring season. Thank you,

Rick

305-251-4406