Published on October 10, 2016

By Thomas Van Hare

On Sunday, October 10, 1943 — 73 years ago in aviation history — the 8th Air Force flew a bombing raid against the city of Münster in Nazi Germany. At the time, America’s airmen were still fairly inexperienced, having only just begun six months earlier flying bombing raids against Nazi Germany. Despite extensive planning, the mission that day became one of the worst disasters in 8th Air Force history. Among those who flew that day, the airmen of the 100th Bomb Group (Heavy) suffered the worst — of the 14 bombers that pressed on to the target, only one bomber made it back. After Münster, the 100th Bomb Group’s nickname would be forever fixed in memory as “The Bloody Hundredth”.

This is the story of the crew of that lone survivor, a B-17 Flying Fortress nicknamed, “Royal Flush” (B-17F-45-VE 42-6087 — LD-Z), flown by pilots Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal and Winifred T. “Pappy” Lewis of the 418th Bomb Squadron.

The Mission Plan

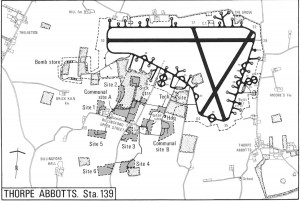

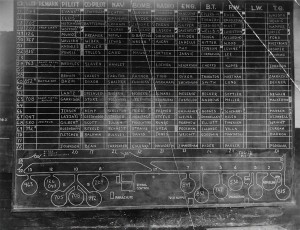

At the 100th Bomb Group’s base at Station 139, Thorpe Abbotts, the early morning of October 10, 1943, began with a mission briefing. In front of a room before the assembled pilots and navigators scheduled for the mission, the group’s senior officers and intelligence briefers stood together before a map with pins and lines marked on it that indicated their route and target. The airmen sat in chairs, already dressed in their flight gear to help keep warm against the bitterly cold morning air of England that late Autumn.

With long pointers, the intelligence officers highlighted the target and reviewed the details of the day’s mission. Waypoints were pointed out along the route and the headings to and from the target were marked along with the times they were expected to arrive at each. The weather was detailed on a separate blackboard that was propped up on a board next to the map. After flying across the English Channel and veering over the Baltic, the bombers were to fly into Germany and then directly toward the target. They were to veer slightly to the south, in hopes of throwing off the German radar controllers as to their true target, before turning back northeast, passing the “Initial Point” (IP), and commencing their bomb run on Münster.

The brief included reconnaissance photos of the target, as well as rendezvous times for supporting fighter aircraft that were supposed to be flying that day to defend the bombers. Those escorting fighters, it was hoped, would help fight off attacks by the Luftwaffe. In 1943, Nazi Germany’s air defenses were at their greatest strength. Every mission the 8th Air Force flew was met by at least 50 to 100 fighters and sometimes even more. There would be losses.

The briefing officer from G2 (intelligence) gave his report, estimating the expected opposition. With a grave tone, he described that approximately 245 single-engine and 290 twin-engine fighter planes might be defending the target. These German fighters would be a combination of single-engine types, such as Messerschmitt Me 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, and twin-engine planes that would likely carry air-to-air rockets, such as Messerschmitt Me 110s, Me 410s, and Junkers Ju-88s.

Hoping to divide German fighter defenses, a diversionary raid of B-24 Liberators was scheduled to bomb another city. G2 assured the crews that this diversionary raid would probably draw off up to half of the enemy fighters. To escort the bombers, the 8th Air Force’s P-47B Thunderbolts had been tasked to trade off in relays both to and from the target.

Münster was no “Milk Run”

The briefers made no effort to paint the mission as a “milk run” and they could see the stress written on the faces of the airmen. The 100th Bomb Group had seen extensive action over the previous few days and had suffered losses. The Luftwaffe was in top form and its pilots were highly expert. Furthermore, flak over the target was expected to be intense and very accurate.

A detailed description of the target followed including the aiming point for the bombardiers. Over the previous two days, the targets had been military in nature, however, the mission against Münster was different. This mission was the first time the 8th Air Force would bomb an entirely civilian target.

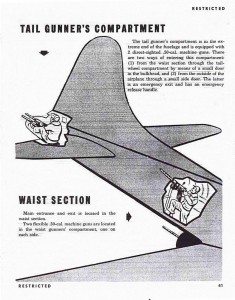

Ominously, the aiming point was Münster Cathedral, located in the very heart of the old city. The cathedral dated from the 14th Century, though that wasn’t told to the flight crews that morning. The crews were told that targeting the civilian population at Münster would deprive Germany of its much-needed civilian railway workers that supported the Nazi war effort. As the tail gunner of the B-17 “Royal Flush”, Sgt. Bill DeBlasio, would later relate, “It seemed reasonable at the time.”

Opposing Sides

For the Münster raid, the 8th Air Force fielded a strong force of 274 B-17 Flying Fortresses from the 3rd Bomb Division’s 13th Combat Bomb Wing (13th CBW). In addition, a total of 216 P-47B Thunderbolts were tasked to fly escort. With that many fighters in the air, the flight crews felt that there was some hope that the fighters would hold off the Luftwaffe and maybe even run up a good score of kills. The German Luftwaffe was certain to intercept the 13th CBW as flew to and from the target — the only question was whether the American fighters would be in the right place at the right time to intercept.

Even if 216 fighters were tasked to support the raid, given the fuel situation, they would have to trade-off. Thus, at any point along the route, only one or two Fighter Groups would be present to escort the bombers. The large diversionary raid by the B-24 Liberators would lure away some of the enemy, possibly evening the odds for the American fighter pilots. Flak over the center center of Münster was predicted to be heavy — most losses, the planners noted, would come over the target and be due to flak.

The Flight Crew of “Royal Flush”

The flight crew assigned to fly the B-17 “Royal Flush” that day consisted of the following:

- ROSENTHAL, Robert, LT, Pilot — nicknamed “Rosie” while in the 100th BG

- LEWIS, Winifred T., LT, Copilot — nicknamed “Pappy” while in the 100th BG

- BAILEY, Ronald C., LT, Navigator

- MILBURN, Clifford J., LT, Bombardier

- HALL, Clarence C., SGT, Top Turret/Engineer

- BOCCUZZI, Michael V., SGT, Radio Operator/Gunner

- DARLING, Loren F., SGT, Waist Gunner

- SHAFFER, John H., SGT, Waist Gunner

- DeBLASIO, William J., SGT, Tail Gunner

- ROBINSON, Ray, SGT, Ball Turret Gunner

New in Theatre

The 100th BG’s newest crew was that of pilots, Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal and Winifred T. “Pappy” Lewis. They and their crew of another eight men (10 in all) were considered inexperienced or “green”. They had just arrived at the 100th Bomb Group as replacements for losses sustained during the group’s previous mission that had been flown against Schweinfurt.

For Rosenthal and Lewis, the Münster raid was only their third mission since arriving in England. The other two raids had been flown over the previous two days — on October 8th against Bremen, and then on October 9th to Marienburg. On the morning of October 10th, they were flying their third consecutive mission day, a rough start for what promised to be a dangerous tour.

At the time, informal USAAF estimates were that the average crew was expected to survive between 12 and 15 missions before getting shot down. A full tour was 25 missions — few were expected to complete a tour and return to the USA. In context, the first crew to survive a full tour of 25 missions was from the B-17 “Hell’s Angels” (#41-24577) with the 303rd Bomb Group, having achieved the nearly impossible 25th mission just five months earlier on May 13, 1943. A week later the crew of the “Memphis Belle” managed it too, and were featured in the famous film of that name.

Since those two crews had survived a full tour of duty, several other crews had made it to 25 missions. Survival of a full tour of 25 missions was still vanishingly rare. Losses were heavy, mission after mission. Furthermore, things weren’t getting better. The odds of surviving were worsening as the 8th Air Force began to select targets deeper and deeper into Germany.

For the crew of Lt. “Rosie” Rosenthal and Lt. “Pappy” Lewis, the B-17F Flying Fortress “Royal Flush” was not their usual plane. Their own B-17F, “Rosie’s Riveters”, had sustained damage on their first mission to Bremen on October 8, two days earlier, and was still undergoing repair. The day before they had also flown “Royal Flush” to Marienburg and had returned in good shape.

“Royal Flush” was to fly in a position toward the rear in the Bomb Group’s formation. From that position, they would have a front-row seat to witness the mission and upcoming carnage. Chillingly, the trailing aircraft in the rear of the formation was often the first to be shot down.

What Can Go Wrong Will Go Wrong

From the start of the mission, nothing worked as planned. First, the hope that up to half of the Luftwaffe’s fighters would go after the diversionary raid flown by the USAAF’s B-24s didn’t work out. Given weather issues and other problems, the diversionary mission was apparently aborted — the records are confusing in this regard. Some records indicated that 39 B-24 may have taken off to bomb Coesfeld, Germany, but may have turned back early. That view is supported by the fact that the B-24 groups took no casualties that day.

In any case, the diversionary raid was either not flown at all or was so small that the Luftwaffe simply ignored it. Instead, the German radar operators and air defense controllers focused exclusively on the main attack, a single bomber stream tracking directly toward Münster. The order went out to all of the fighter-interceptor units to prepare for take-off.

Worse yet, the weather kept much of the scheduled fighter escort on the ground. Despite that, the 13th CBW bombers took off and, even when it was realized that there would be only very limited fighter escort, they were not recalled. For their part, the bombers flew on into Germany, completely unaware that their fighter escort would never show. In retrospect, the disaster to come was all too predictable.

The 100th BG was flying in the most dangerous position at the back of the larger 13th CBW formation. Without knowledge of the multiple failures already plaguing the mission, the bomber force began the long flight toward the Dutch coast and beyond.

The German Luftwaffe’s fighter controllers concentrated everything they had on the main bomber stream. At the many interceptor bases across northwestern Germany, pilots strapped into their planes. Each plane’s fuel tanks were topped off. Rockets were loaded under the wings. Ammunition was loaded for each gun. As the bombers crossed the coast over the Netherlands, dozens of German planes were taking off. Climbing up to 20,000+ feet, they began forming up for the attack.

The Luftwaffe planes were Fw 190s, Me 110s, Me 109s, Me 210s, Me 410s, and Ju 88s. Many carried the Luftwaffe’s newest air-to-air rockets, designed expressly for the purpose of attacking American bomber formations. Many of the single-engine fighters were equipped with the new heavy cannon and machinegun pods hung under the wings, adding to the firepower that they could use in attacking the bombers.

Leading the 3rd Bomb Division’s 13th Combat Bomb Wing was John K. Gerhart, commanding officer of the 95th BG. Behind Gerhart’s 95th BG was the 390th BG and the 100th BG. In turn, the 100th BG was led by pilots Major Eagan and John Brady flying in the B-17 “M’lle Zig-Zag”. The 13th CBW flew in the newly developed “combat box” formation that had been designed to maximize the defensive effect of the combined firepower of the formation’s many machine guns.

Before flying over the Dutch coast, quite a few of the bombers from the three groups of the 13th CBW aborted with various engine problems and other issues. This was to be expected. This was, after all, the third straight mission day. Those planes and crews that aborted were the lucky ones. In the 100th BG, 21 bombers set out. Of those, seven aborted and turned back. This left 14 B-17s with the group to continue toward Münster.

They encountered little resistance as they passed over Holland. As the bombers headed into Germany, they realized that the promised fighter escort was nowhere to be seen. Perhaps, they hoped, the P-47s were just running late and would catch up.

First Fighter Attacks

As the formation crossed into Germany, no attacks had yet come. However, as the bombers neared Münster, everything changed. At 14:53, just nine minutes from the scheduled start of the bomb run — about 25 miles from Münster — the Luftwaffe commenced its first attacks. First, a series of Me 109 and Fw 190 fighters slashed through the formation, firing their guns. The extra 20mm cannons mounted under their wins quickly took their toll on the bombers. These cannons were the most deadly types of guns in the air — a 1945 survey revealed that 6% of the bomber crew casualties were caused by 20mm shells, three times more than by enemy machine guns, which accounted for 2% of casualties. Flak was always the biggest killer, however, and the survey showed 64% of the casualties were credited there.

Immediately after the Me 109s and Fw 190s had finished their attack, a combined force of Me 110 and Me 410 Zerstoren came in. These flew toward the formation from the rear and began firing rockets. As the trailing group, the 100th took the brunt of these attacks. Almost immediately, the group’s leader, Eagan in the B-17 “M’lle Zig-Zag”, was hit. Despite the damage sustained to the center of the fuselage, Eagan didn’t pull out of the formation. Instead, he slowed his plane and began to descend. The 100th BG followed the lead plane as it began to slow and descend alongside and the formation began to fall apart.

Slowed, the 100th BG fell behind as the 13th CBW’s other two bomb groups steadily pulled ahead toward the target. Seeing one group descend out of the protective envelope of fire from the wider formation, predictably, the Luftwaffe pilots concentrated their attacks on the 13 remaining B-17s of the 100th BG.

One of the bombers with the 100th BG, piloted by Keith Harris, normally from the 390th BG, recognized the disaster to come even as it was unfolding. Pushing his throttles forward, he climbed out of the formation to join with the 95th BG as it passed overhead. Another of 100th BG’s B-17s, “Pasadena Nina”, followed as well. The remaining eleven bombers of the 100th BG faced the Luftwaffe’s attacks alone.

In the seven minutes that followed, eight of the remaining eleven aircraft in the 100th BG’s formation were lost to intensive fighter attacks. The B-17 “Aw-R-Go” was hit and caught fire. As the crew baled out, it soldiered on for a short while before exploding in midair. One crew member, the tail gunner, SGT Charles A. Clark, couldn’t get out in time and was killed in the explosion. The other nine either jumped or, in at least two cases, were blown clear of the plane. One of those, T/SGT Orlando E. Vincenti, had been fighting a fire in the radio room and when he jumped his parachute was on fire. He plummeted to his death. The other eight survived and were captured.

Amidst the chaos, the B-17 “Sexy Suzy, Mother of Ten” was hit by 20 mm cannon rounds from a fighter and caught fire. While some accounts state that the plane collided with a damaged Me 109, the crew reports do not support that. Only four of the ten men on board baled out successfully — all were captured — and the rest were killed. Another bomber, the B-17 “Sweater Girl”, went down after it lost the #2 engine — the crew baled out and the plane crashed at Ostberven, near the Dormund-Ems canal.

Moments later, the B-17 nicknamed “Stymie” was hit hard and the crew turned for home. The German fighters pounced but soon let it go as it was badly damaged and descending rapidly. The Luftwaffe kept its focus on the main formation. Flak subsequently downed the plane, though the crew was able to belly land the plane in a field. The entire crew survived and was captured.

The group leader, Eagan in the B-17 “M’lle Zig-Zag”, was finally downed by more fighter attacks. Eagan’s entire crew parachuted to safety and was taken prisoner. Finally, just three B-17s remained and onboard “Royal Flush” things were desperate. A rocket from the attacking fighters had put a huge hole in the right wing and taken out two engines.

Bomb Run

Undeterred, the last three bombers of the 100th BG turned northeast at the IP and began their bomb run. The 13th CBW formation had gone on ahead to bomb Münster. To the remaining planes of the 100th BG, these planes were little more than distant specks, racing ahead. As German flak intensified as the three passed the outer limits of Münster. Finally, the Luftwaffe’s fighters ended their air attacks and withdrew. They would orbit and await the surviving bombers after they left the target area.

After passing the IP, the rule was that bombers would have to fly straight and level at exactly 150 mph. This lasted for about two minutes and gave the bombardiers time to aim and drop their bombs. Only then would the pilots take control and turn back toward England. On paper, it meant that the bombers could be more accurate in dropping their bombs — in practice, it meant that the German flak gunners had an easy time aiming their shells.

In this attack, the larger numbers of bombers in the combined 13th CBW had shared the fire from the deadly flak gunners. Together, they dropped their bombs starting at 15:03. The last bombs hit their targets at approximately 15:15. With that, the main force of the 13th CBW turned toward home. Next came the three bombers of the 100th BG. They were heading into the target alone, which gave the German flak gunners the opportunity to concentrate their fire. There were no other targets in the skies over the city.

At once, the sky filled with puffs of black from the explosions of the flak rounds. As usual, they were shooting with extraordinary accuracy. The Luftwaffe boasted well-trained flak crews and sophisticated radar and gun direction systems. As a result, the German flak was right at the correct altitude. The shell bursts were perfectly aimed with the exact lead required to target the three bombers as they passed over the city center. Tiny bits of shrapnel cut through the fuselage and wings of “Royal Flush” from nearby explosions.

With no enemy fighters around, one of the waist gunners on “Royal Flush”, Sgt. Loren Darling, crossed the open bomb bay on the narrow catwalk to look in on the two pilots, “Rosie” Rosenthal and “Pappy” Lewis. He peered up into the cockpit from behind and looked out the windshield. He could see the other two 100th BG B-17s just above and ahead. These were the B-17s “Shackrat” and “Horny”. Suddenly, both bombers took direct hits from flak. Later, he recalled, “Just like that, they were balls of black dust. Bomb bay doors were open, ready to spill out twelve 500-pound high-explosive bombs, then Boom. Gone forever.” Each plane had carried ten men — he didn’t believe that there were any survivors from either.

All but one of the 100th BG’s B-17s had been hit and destroyed. Alone in the skies over Münster, two engines out and streaming black smoke, at 15:18, “Royal Flush” dropped its bombs and turned toward home. The armada that had once been the 100th BG was no more. The other two planes that had flown ahead from the 100th BG formation had also dropped their bombs on the target — this was Capt. Keith Harris, who was flying with the 100th BG that day in the B-17 “Stork Club” and Lt. John Justice in the B-17 “Pasadena Nina”.

“Pasadena Nina”, however, wouldn’t make it back to England. The bomber was hit by flak over Holland and spun in — two of its crew were killed, seven taken POW, and one, Lt. Justice himself, evaded capture and made it back with the help of the Dutch Resistance. He only returned to Thorpe Abbotts many months later.

As soon as Rosenthal and Lewis left Münster, they searched for other bombers of the 13th CBW, hoping to rejoin the others for mutual protection. By the time they had finished bombing the target, “Royal Flush” had fallen approximately :15 minutes behind the first bombers that had struck Münster. The closest formation was perhaps just four or five minutes ahead, but at the speeds they were flying, that meant that they were already between 15 and 50 miles away — well out of sight. With two engines out, they had no hope of catching up. In all directions, as Rosenthal and Lewis scanned the skies, they found no other airplanes. It was as if the skies had suddenly cleared.

In any case, rejoining with the 13th CBW would not have offered much protection. The German fighters had resumed their attacks on the formation. There were many casualties. In the 390th BG, eight aircraft were lost — nearly half the entire group as 18 of its B-17s had flown to Münster. The 95th BG had fielded 19 B-17s and, of those, five were lost to enemy fighter attacks. The rest of the 3rd BD lost an additional four planes. Most of the surviving planes suffered heavy damage.

More Fighters!

Rosenthal and Lewis soon found themselves facing dozens of attacking Luftwaffe fighters. They were alone and an “easy target”. The Luftwaffe fighters easily spotted the lone bomber because it was trailing black smoke. Worse yet, “Royal Flush” was slowed and steadily losing altitude.

As the first fighters streaked in to finish off the wounded bomber, Rosenthal and Lewis began to pull the bomber around the sky in defensive maneuvers to throw off the attackers’ aim. Since the control surfaces were directly connected by push wires to the control yokes in the cockpit, it took the combined muscles of both men to maneuver the big B-17. The tactic worked as Germans had not expected the B-17 to suddenly bank steeply and turn away so violently. Then, as they circled around, they watched it reverse and do it again against the next attack.

The maneuvers were so severe that the waist gunners in the back of the bomber could barely hold on. Nonetheless, they tried to fire at the German fighters as they flashed past. Only the tail gunner and ball turret gunner were properly strapped in. The Germans recognized that an attack from the rear would give them the best chance of downing the lone bomber quickly. Their next attacks came in next directly from behind. The tail gunner, Sgt. Bill DeBlasio, began to fire at them with his two .50 caliber machine guns.

In a letter to “Rosie” Rosenthal written years later in 2001, Sgt. DeBlasio recounted the events of that day. He began by mentioning that it had been seven years since he had suffered his last “flashbacks” — in other words, for 49 years, the events of that day over Münster had still haunted him. The letter was the first time he would recount the mission after all those years.

He reported that the German fighter planes were coming in in lines of four abreast and were holding their fire until they were only 800 yards away. The first four to attack flew right into his guns:

“I lined up on the number two man from my left and fired three short bursts. His left wing flew off over his plane and crashed into the plane to the outside. Both went down on fire. I then switched to their inside plane on the right and fired at him. Smoke started coming from the plane and the canopy came off, the plane rolled over ejecting the pilot. I couldn’t follow his plight as I had one more plane to deal with. Just as I brought my sights to bear on him, he peeled off to his left (my right).”

The German fighters pressed in, undeterred by the first losses. After all, “Royal Flush” was a lone bomber with two engines out — a damaged straggler. Further, they could see that the plane had clearly suffered a lot of battle damage already. Finishing the job should have been easy. Their only mission was to ensure that the bomber and crew didn’t make it back to England, as then they would come and bomb again on another day.

The gunners kept up return fire as Rosenthal and Lewis threw the plane from left to right attempting to dodge the attacks. Incredibly, their flying caused many of the attackers to miss, but they were losing altitude fast since the bomber had only two engines running. Both pilots were braced so that they could hold the left rudder pedal pressed to the floor to counteract the torque from the unequal thrust. DeBlasio, however, was proving to be an ace shot — literally.

“There was a period of about 4 or 5 minutes respite then they started again. I believe we may have been about 15 thousand feet as two Ju-88’s joined the fray, with two engines out there was no way we could maintain high altitude. Again there were 4 FW 190’s, only this time they were staggered more or less one behind the other, not in a straight line as were the first bunch. This time however the two Ju-88’s were on each end of the 4 fighters making six aircraft lined up on us. For some unknown reason, I decided to try for the bigger aircraft first. I thought I noticed something hanging from the bottom of their aircraft. About that time, here come the rockets. A total of 8 rockets come at us in about 1 minute of time, all missed. It dawned on me that what I saw beneath the aircraft were their flaps. They needed to lower their flaps to give them a more stable platform for their rockets.

“I started firing at the Ju-88 on the left and soon he was on fire and sliding off on his right wing. The other aircraft had closed too within 600 yds and I just started raking my fire from left to right and back again. During this exchange two of the FW-190’s in the center crashed into each other, as I believe I hit them both at the same time. So we have a total of six planes shot down and we don’t know how many, if any, were damaged.”

Incredibly, Sgt. DeBlasio became an ace that day in a single mission. Sadly, he was one of those bomber gunners whose exploits remain relatively unrecognized. After the war, it was determined that most bomber formations vastly over-claimed the numbers of Luftwaffe aircraft shot down, often double or triple counting kills as different bombers fired on the same attackers or claimed as shot down German planes that were merely damaged and chose to break off the attack and land.

In the case of DeBlasio’s six fighters that he claimed to have shot down, none were officially recognized or verified. No other aircraft witnessed the valiant defense he put up. However, his descriptions leave little doubt as to what happened. In the attack on Münster, the 8th Air Force bomber crews claimed 105 Luftwaffe fighters shot down — German records reflected losses of just 25. Most likely, Sgt. DeBlasio accounted for six of those. In all likelihood, he made a difference and saved “Royal Flush” that day.

Finally, the last of the German planes broke off the attack and headed back to their bases, running low on fuel. Much of the Luftwaffe had concentrated on attacking the other aircraft in the 13th CBW, miles ahead. As they flew over Holland, some of the promised escort of P-47 Thunderbolts finally arrived. A brief dogfight followed against the retiring German fighters, who had hoped to avoid a dogfight with the escorts. Low on ammunition and short on fuel, the German fighters were carrying the extra load of the heavy gun kits strapped under their wings. The P-47s claimed 19 German fighters downed in exchange for perhaps one loss.

“Royal Flush” saw none of that. Somehow, the B-17 had survived, although the situation was still desperate. The bomber couldn’t hold altitude on the power remaining from the two engines, both on the left wing. Passing over Holland, they watched as light and inaccurate flak was fired at them. That too ended as they crossed the coast and headed toward England and yet, with the steady descent, Rosenthal and Lewis didn’t think they could make it back to base. They might have to ditch in the water. In the chill of October, they might not survive the cold in the water while awaiting rescue — from either side, as the Germans too patrolled the waters off Holland with their boats, hoping to pick up and imprison downed Allied airmen.

Rosenthal ordered the crew to throw out anything they could find. Fire extinguishers, ammunition, extra oxygen bottles, and other gear and machine guns were tossed through the openings at the two waist gunner positions. DeBlasio fired off his remaining ammunition to clear his two guns, knowing that the bullets added a lot of weight too. Then, he unstrapped from the tail gunner position and came forward to assist throwing out more. As much equipment as could be removed was tossed out. Hundreds of pounds lighter, the rate of descent was reduced. With this, they could make to the coast of England after all.

The damage to the plane was remarkable. In one attack, a 20mm shell from one of the attacking Me 109s or Fw 190s had ripped through the fuselage of “Royal Flush”. Both waist gunners were injured badly. The radio man, Sgt. Michael Boccuzzi, administered first aid and morphine. Both survived but had to be sent back to the USA, given the severity of their injuries.

Finally, “Royal Flush” made it back to England. They found the airfields covered in low cloud. After several turns, they located Thorpe Abbotts, which was closer to the coast and therefore less socked in. Firing emergency flares, they made an emergency landing with wheels down. The B-17 rolled to a stop and Rosenthal and Lewis shut down the engines. The crew piled out of the plane onto the mowed grass of the runway. Sgt. DeBlasio later recounted the end of the mission:

“I remember sitting on the grass and vomiting for what seemed like an eternity. I was asked to secure my guns, which I did. I do not recall whether any of us put in claims for downed aircraft, as this was superficial compared to losing the entire Group except one plane. Besides, it wouldn’t have done any good as we all knew any aircraft shot down had to be verified by at least one or two aircraft other than your own. I remember your [written to Rosenthal] going in the ambulance with John Shaffer (waist gunner).”

Sgts. Shaffer and Darling, the two waist gunners were taken to the base hospital. Both were awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart.

Recounting the Losses

Based on Missing Aircrew Reports, the following losses from the 100th BG were recorded with the reasons for each loss cited:

B-17F “El P’sstofo” #42-30090 — 349BS/100BG [XR-B], Pilot: Winston MacCarter — air attack took out engine #1, subsequently crashed at Haltern. All ten of the crew survived and were captured.

B-17F “Sexy Suzy, Mother of Ten” aka “Holy Terror” #42-30723 — 351BS/100BG [EP-D], Pilot: Bill Beddow — collision with an attacking Me 109, caught fire, and exploded from subsequent flak hits, crashed near Ostbevern.

B-17F “Sweater Girl” #42-30047 — 350BS/100BG [LN-Q], Pilot: Rich Atchison — during air attacks hit by the wreckage of a Me 109 and B-17, crashed at Schirl-Beverstrang, 4 miles east of Ostberven, near Münster.

B-17F “Leona” #42-3433 — 359BS/100BG [LN-W], Pilot: Robert Kramer — The plane was hit by flak and caught fire. Three crewmembers were unable to bale out, including 2nd LT Kramer; it was the crew’s third mission. According to German records, the plane came down “at Lambeck near Wulfen, 100 meters north of Schloss Lembeck”.

B-17F “Aw-R-Go” #42-30725 — 359BS/100BG [LN-Z], Pilot: Charles “Crankshaft” Cruikshank — air attacks by fighters set the plane on fire; it exploded and came down at Lienen, 15 miles from Münster. The tail gunner was killed in the fighter attack, and eight of the nine remaining crew baled out successfully and were captured. The left waist gunner, S/SGT Donald Garrison, did not bale out, but was blown clear of the aircraft and seriously wounded. After capture, his leg had to be amputated (he survived the war).

B-17F “M’lle Zig-Zag” #42-30830 — 418BS/100BG [LD-U], Pilot: John Brady — aircraft attacks took out engines #1 and #3, then the plane was hit by flak and finally crashed at Nottuln-Stevern, 12 miles west of Münster. All but one of the crew survived. The 418th BS CO, Major Egan, was an eleventh crewman on the flight — he too baled out and was captured.

B-17F “Slightly Dangerous” #42-30734 — 351BS/100BG [EP-G], Pilot: Charles Thompson — shot down by a fighter in a head-on attack, lost the right wing and the aircraft exploded and crashed near Walingen, 6 miles west of Münster; three KIA and the rest captured.

B-17F “The Gnome” aka “Invadin’ Maiden” #42-30823 — 350BS/100BG [LN-F/Y], Pilot: Charles Walts — shot down by an Fw 190 attack that took out engine #2, catching the wing on fire, and the aircraft exploded, broke in half, and crashed at Hohenhalte, 6 miles west of Münster. Five of the men were KIA, the rest captured; one man, the navigator, 2nd LT Louis H. Oss, plummeted over 20,000 feet down in the spinning nose section before finally getting out only 1,500 feet from the ground.

B-17F “Horny” aka “Forever Yours II” #42-30023 — 349BS/100BG [XR-M], Pilot: Ed Stork — hit by flak, caught fire and crashed at Amelsbeuren, 3 miles south of Münster. Three days earlier, the crew had lost three engines and managed to fly 400 miles back to England and land successfully. Their luck ran out at Münster, however. Two of the ten-man crew were killed, the rest baled out and were captured.

B-17F “Shack Rat” #42-30087 — 351BS/100BG [EP-M], Pilot: Maurice Beatty — hit by flak and crashed at Vynen/Xanten, near Münster. All but two of the crew were killed.

B-17F “Pasadena Nena” #42-3229 — 349BS/100BG [XR-A], Pilot: John Justice — after the bomb run on the flight back, flak took out engine #4, plane spun in and crashed near Barneveld, Holland. Two crewmembers were KIA and seven were captured. The pilot successfully evaded capture, made contact with the Dutch Resistance, was interviewed by a British MI9 agent named Dick Kragt [cover name “Frans Hals”], the only escape line and evasion agent who worked in Holland and survived the war. A month later, Justice was able to return to England. Two months later, the Dutch family that kept him hidden and safe was arrested and sent to the Wobelin/ Neuengamme labor camp near Hamburg — he died three weeks later. His wife and child were imprisoned at camp Amersfoort and later Westerbork in Holland and only barely survived the war. It was the crew’s 17th mission.

B-17F “Stymie” #42-3237 — 418BS/100BG [LD-R], Pilot: John Stephens — damaged from aircraft attacks and turned for home, hit by flak and belly landed at Holthausen.

B-17F “Lena” #42-3433 — 350BS/100BG [LN-W], Pilot: Bob Kramer — flak blew off the right wing, 5 miles north of Dorsten, 25 miles SW of Münster.

Aftermath

On the ground at Thorpe Abbotts, the 10 man crew of “Royal Flush” was all that remained of the 140 men and 14 airplanes that had flown to Münster from the 100th BG that day. The 100th BG had suffered the ultimate blow. As well, in the previous two days, six other aircraft had also been lost — a total of 60 additional airmen. Some had survived and parachuted out and been taken prisoner.

After debriefing, the crew of “Royal Flush” went for dinner. They sat in a mostly empty dining hall. Those flight crews that had aborted were there, as were several crews from a few of the bombers from the 95th BG that had been forced to land at Thorpe Abbotts due to the bad weather at their own base. That night, the copilot, “Pappy” Lewis, walked over to the Officers Club, peered in, and found it empty. After a drink, he went back to his quarters and turned in. Three days after, the crew got sent for rest and recuperation at an elegant British manor hall, where for a short time they were feted and given the opportunity to wander the grounds and recover before returning to the 100th BG to fly more missions.

When they returned at the beginning of November, the 100th BG was full of fresh new faces. Replacements flight crews were steadily arriving from the USA with new B-17s and many questions. The crew of Rosenthal and Lewis, with its three missions, having been considered green before the Münster raid, were now the “old hands” to the new crews, who hung on their every word.

Postscript

The war would go on for one and a half more years. Against all odds, both pilots, “Rosie” Rosenthal and “Pappy” Lewis, would survive their full tours. All of the men that flew with them that day made it through. Rosenthal, who had been a lawyer before the war, and his trusted copilot, “Pappy” Lewis, served together in the War Crimes Commission that prosecuted Nazi war criminals at Nuremburg after the war. Both sat in on the hearings of Hermann Goering, the once-vaunted former head of the Luftwaffe.

During their service, both earned many medals and awards. For the mission over Münster, Rosenthal was awarded the Silver Star. Both men would return and build lives and families after the war and only rarely talk of their experiences. They considered themselves to be just the lucky ones who survived. The men of the “Greatest Generation” never put much stake in the claims that they were heroes. As much as any other, those who made up the crew of “Royal Flush” and “Rosie’s Riveters” were the heart and soul of the 100th Bomb Group.

From its first mission on June 25, 1943, to its final mission on April 20, 1945, the 100th BG lost 229 aircraft, in which 768 men perished (KIA and MIA). An additional 939 men bailed out and were made prisoners of war. Thus, of the 1,707 men who were lost or captured throughout the entire war, 130 were lost just from that single mission over Münster — nearly 8%.

One Final Word

In all, Münster suffered 102 air raids between 1940 and 1945, mostly night raids by the RAF’s Bomber Command, causing moderate damage, though life went on fairly normally in the city. The first daylight attack on Münster by the American bombers was this one, on October 10, 1943. Approximately 700,000 bombs were dropped on the city in both day and night bombing raids. The death toll topped 1,600, a mercifully low number only possible because the majority of the citizens in the city had been evacuated once the attacks began.

By the end of the war, 60% of all buildings in Münster were destroyed — in the old town at the city center, 90% were destroyed. All utilities were destroyed, leaving the city without water, gas, or electricity. When the Allied forces overran the city in April 1945, the damage was so bad that their progress was hindered by the piles of bricks and debris that blocked most of the streets. Only 26,000 people remained.

As for the 14th C. cathedral at Münster that served as the aiming point that day, it survived the war and remains standing today. The rest of the city was reduced to rubble in subsequent bombing raids in 1944. The rebuilding of the city would take years. Today, Münster’s population has reached 300,000.

I enjoyed reading about your report on the Munster mission with the 100th Bomb Group, I’m always interested in new information on the October 10, 1943, attack from the USAAF. I haven’t seen your report before.

I’ve been to many 100th Bomb Group reunions and met the men who flew those missions. Rosie was a great person and very friendly. I remember in Houston I gave him a VHS tape of the 100th and he gave me a big hug. I’ll never forget it.

I’m planning on being at the next reunion in Dallas in December 2021. I did some research for a film in the National Film Archives and found some footage of this mission to Munster. It’s very short and shows the 94th Bomb Group over the city, under attack from the fighters. Flak and bullets all around. I also obtained a few different DVDs on the city of Munster on the city’s history and the people of Ulm. The footage shows a nice community, enjoying the day with there events.

It’s so tragic what can happen when one man comes in with ignorance and hate. The Nazis brainwashed an entire country, promising a better life beyond the financial hardship they were experiencing in the early 1930s.

An incredible story. One point though, the picture of the “rubble strewn streets of the city of Münster” does not show the 13th Century cathedral, which never had a spire.

What can be seen in the picture is the spire of the Lambertikircher – St Lambert’s Church – to the East of the cathedral.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Lambert%27s_Church,_M%C3%BCnster

There is more information available about the crew, crash site and plane. It’s my town and I interviewed several old people there and collected some information. I have an old picture of the crash place that shows the plane. It’s really a very short distance to the west of the building from Elfers. Many people saw the plane circling and the men jumping from it. The collection of the men by German forces was not so “clean” as they thought. Some kids saw the driver of ambulance from Nottuln kick one of the men as he entered the car. Some of the witnesses feared that the plane would hit one of those descending in their parachutes because the plane was in a long spiral downward toward the ground. When the plane was finally down, the farmers came and dismantled all they could to take what they needed. One used the rear wheels on a wheelbarrow. Another took the headphones. Another removed the rear gun (that exists still today in the area). At the end of the war, it was thrown into a dung heap to hide it. Then many years later, they recovered it and now it is on a wall… Many people visit the crash place to see one of the “enemy” that once flew over their hands.