Published on February 27, 2017

By Thomas Van Hare

On the morning of June 1, 1921, the Ku Klux Klan and the white population of Tulsa made their move. At the sound of three blasts from a siren, they stormed the city’s wealthy African-American district of Greenwood. The defending African-American citizens were ready. It had been a tense night of preparation. This was a battle they knew would come.

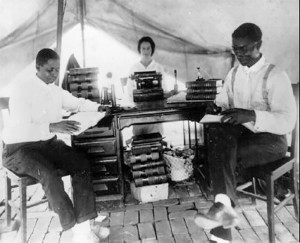

Until the attack, Greenwood was a prosperous, wealthy, and well-educated community. Despite their prosperity — and maybe because of it — the African-American community had watched with increasing concern as the KKK steadily rose in power in the city. The Greenwood community knew they were in a fight for survival. They were committed to defend every block of the community they had built.

Both sides were well-armed. However, the KKK had one thing that the African-Americans did not — air power.

WATCH THE VIDEO!

The first firebombing of a city did not take place during the Second World War but two decades earlier. It did not take place in some overseas conflict either — it took place in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was the first and only aerial bombing of an American city in history and didn’t involve a war with a foreign power. Rather, it pitted Americans against Americans. Horrifically, it was also a battle along racial lines.

Seeds of Conflict

The all-night stand-off between the white and black communities in Tulsa had begun on May 31, 1921. Mobs of white men had gathered at the courthouse calling for the lynching of an African-American man interned inside. As it turned out, the man wasn’t so much imprisoned as being protected from the mob. The man was held for an alleged crime that law enforcement knew he did not commit. Sheriff McCullough, Tulsa’s chief law enforcement official — and a white man — made his best effort to protect the young man and dissipate the anger. While Sheriff McCullough’s actions saved the man’s life, they did little to save Greenwood. Despite several meetings with the angry mob outside, nothing cooled the murderous intent of the assembling KKK-backed mob.

As the day wore into evening, word of the white mob spread through the African-American community in Tulsa. The whites’ demand for the young man’s lynching was the product of the Ku Klux Klan. In just a few years, the Klan had grown from being a minor presence in the city of Tulsa to a large organization with 3,200 members. This was a city with a population of approximately 75,000. Tulsa County, including the city and surrounding areas, numbered about 110,000.

The Klan’s expansion piggy-backed on the fact that many whites were envious of the successes enjoyed on what was known as “Black Wall Street”, the popular name for the city’s African-American business district. Nonetheless, even if latent racism was clearly present, most members not violent extremists. To help push them along, the racist radicals who ran the Klan had a plan. They would use a carefully crafted media disinformation campaign to create the anger they needed to achieve their most evil goals. All the public knew was what had been published in the Tulsa Tribune — and that alone proved to be enough to incite widespread public anger.

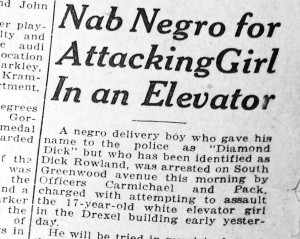

Disinformation in the Tulsa Tribune

As it happened, the newspaper story was contrived falsehood, carefully composed to incite violence against the African-American community in Tulsa. The “journalists” were probably were associated with or at least influenced by the KKK. In their article, they claimed that the young African-American that Sheriff McCullough was protecting had attempted to rape the 17 year old “orphaned” white woman. In actual fact, it was the black youth whose name was Dick Rowland, who was the orphan. Along with his two sisters, he had been adopted by the Rowlands, a black family in Tulsa. The rest of the story was only very loosely based on the truth. The article even went so far as to make up a nickname for the young man, “Diamond Dick”. It was carefully selected to create an image of the youth as a cocky, bejeweled street criminal prowling the streets and showing off — just the sort of person who they hoped could be believed to have attempted to rape a poor, orphaned white woman.

Outraged at the prospect that a “pure white woman” might have been attacked by an African-American, an angry white mob gathered outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held. Word spread quickly in both communities of the confrontation. Until that date, however, the two communities — black and white — had lived together peacefully for years. Now, however, recognizing the injustice at hand, groups of African-American men came armed with rifles and pistols. They stated that they were not there to fight, but rather to offer their help as volunteers to the white Sheriff, who was also intent on protecting the courthouse and the young man from the white mob outside.

Recognizing the potential for a misunderstanding, twice Sheriff McCullough sent the African-American volunteers away. He recognized that, even if their intent may have been to defend the young man and prevent him from being lynched by the angry mob, their very presence would likely only escalate the situation. His worry proved to have merit when on the second occasion, the white mob opened fire on the vastly outnumbered African-American men. The latter numbered perhaps 75, while the white mob numbered in the hundreds. As the African-American volunteers were departing the area, some of what were probably the KKK’s men in the white mob started shooting.

Two of the African-American men fell dead. The rest of the African-American volunteers turned and fired back in a devastating and concentrated volley. Some reports claim that as many as ten white men were killed. In the panicked moments afterward, the African-Americans withdrew to a position a few blocks away.

With nightfall, nothing cooled the hotheads among the white mob. Not only was the young black youth still protected in the courthouse, but now a number of their own were shot dead. The KKK rallied and planned an all-out attack, intending to banish all of the African-Americans from Tulsa. The KKK sent out calls for their members throughout the area to come and join the fight. For their part, the African-Americans vowed to defend their community from an assault they knew would soon come. The white mob vowed to get revenge for their losses and seize the young Dick Rowland for a lynching. Amidst it all, Sheriff McCullough held firm.

Who was Dick Rowland?

The young man at the center of the issue was named Dick Rowland. He was a 19 year old delivery man and shoe shiner, well-known in the community. His alleged crime was the “assault” of a white woman that supposedly had taken place on the 3rd floor of the Drexell Building in downtown Tulsa, when the young man entered the elevator. The white woman who was allegedly accosted, who was named Sarah Page, immediately denied any claim of “assault” and declined to press charges. Nonetheless, the newspaper published the account otherwise. In fact, it is entirely likely that Sarah Page and Dick Rowland knew each other fairly well, at least by sight — and perhaps even better than that.

The shoeshine business owner that employed Rowland had arranged that the company’s employees could use the “Colored” bathrooms that were located on the third floor of the Drexell Building. Sarah Page operated the elevator in the building. Thus, probably she saw Rowland at least a couple of times a day.

One African-American journalist, Mary E. Jones Parrish, later claimed that the so-called, “assault”, may have been that Rowland accidentally stepped on Page’s foot when boarding the elevator after using the bathroom upstairs. This caused her to cry out in pain. A clerk working the building on the floor ran to see what was happening. When Rowland saw the approaching clerk, he panicked and ran from the building. Like Page, the clerk too recognized Rowland by sight. The clerk immediately called the police to report the “crime”, probably over Sarah Page’s objection. It wasn’t long after that Rowland was arrested, reportedly at his home.

Whatever actually happened that day, on May 30, 1921, the news article that followed the next day was as sensational as it was fabricated. Dick Rowland was claimed in the article to have identified himself as “Diamond Dick”. The woman was stated in the news article to have seen him looking up and the down the halls in a suspicious manner before attacking her, ripping her clothes. Even the moniker, “Diamond Dick”, seems doubtful in retrospect, although the article claimed Rowland used that title to identify himself because he allegedly wore layers of gold and diamond jewelry — the absurdity of that should have been obvious based on the pay rate of shoeshine boy and delivery man. The “assault” of the young “orphaned” women was written as if it were the gospel truth. No dissenting view was presented.

Predictably, the article had an effect — the journalists were most probably looking for an incident to stir up trouble. For the KKK, the false claims in the newspaper gave them the pretext to get the support needed to launch their full-on assault of the African-American district in Tulsa.

Another story that some say is that Sarah Page and Dick Rowland may have had a secret, interracial relationship. If so, the “assault” was certainly misreported. It seems more likely in that light that the matter involved the aftermath of a lover’s fight. Others, including lawyers who regularly had their shoes shined by Rowland, knew the young man well because he was the adopted son of a local African-American businessman. Most simply knew that the charge couldn’t be true. Many of the city’s attorneys even commented as such at the time, though the journalists showed little interest in quoting them. To the knowledge of the attorneys, Rowland simply wasn’t violent or aggressive at all. For them, for Rowland to have attacked a woman at all was simply too out of character to be even remotely believable.

Nonetheless, events quickly spiraled out of control.

The main incitement came when the Tulsa Tribune supposedly blared a headline late on May 31 in the city edition of the Tulsa Tribune (recalled by residents later, but all copies have been lost) calling on the populace to, “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” The public went wild based on the “fake news”. The KKK rallied many to support their call for a public, extrajudicial lynching.

When dawn broke, the battle for Tulsa began.

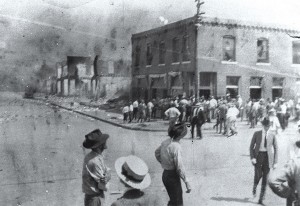

As the first rays of sunlight touched the city, a siren blared three times as the signal to begin the attack. The first white man to rise in the charge was cut down when a defending African-American sniper hit him with a single shot from his rifle. A rallying cry went up and soon crowds of hundreds of white men charged forward, intent on rampaging through the streets of the African-American district of Tulsa. Many of these were members of the KKK.

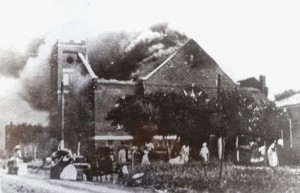

The white mob pressed toward the center of the African-American community, at the center of which was their church, the Mount Zion Baptist Church. As they advanced, they were shooting any who stood in their way. They began setting fire to homes, meaning to burn all of the residences as well as the African-American business district. This area was so prosperous and successful that it was locally known as the “Black Wall Street”. On the map, it is defined as the areas along Archer Street and Greenwood Avenue in downtown Tulsa.

Not unexpectedly, resistance against the KKK-led white mob was fierce. A running street battle followed. It wasn’t long before several homes were burning. Many among the African-American defenders were shot and injured. Some were killed. Many men stood guard, hoping just to defend their homes, and putting up stiff resistance on their own as the white mob advanced. Without an organized force, however, most of these ultimately shot and killed. Tulsa’s leading medical doctor died on his doorstep as he retreated into his house, firing back with his rifle. African-American lawyers, business owners, family men, and workers battled the mob at every house and corner.

The defending African-American community was vastly outnumbered, however. Soon many homes on the outer fringes of the district were burning. Black smoke filled the air. The main street and commercial district of “Black Wall Street” and the community’s church, however, still was beyond the reach of the advancing armed mob. Despite the casualties, the defenders were holding their ground, more or less. The attack by the white mob was in danger of stalling and being driven back.

From the start, the Governor of Oklahoma, Gov. Robertson, declared martial law. The Oklahoma National Guard was mobilized and quickly sent in to stabilize the situation. The forces deployed quickly under the command of Major L.F. J. Rooney, himself a veteran of World War I.

Likewise, Tulsa’s fire department tried to respond to the first fires. However, its engines were fired on by the white mob, then by the African-American defenders. The unarmed firemen retreated, finding themselves prevented from entering the African-American districts and unable to fight the fires. The National Guard mounted its weapons and drove into the chaos, hoping to stabilize the situation with a show of force. None of the official institutions of government were favoring the KKK — not the National Guard, nor the Sheriff, nor the fire department, mayor, nor Governor of Oklahoma. Yet confusion dominated the thinking on the streets — the African-Americans assumed that any armed white coming into sight was on the other side.

Hoping that a show of force would bring order, the National Guard mounted a machine gun on the flatbed of one of their small trucks. Then they drove it directly into the Greenwood District, thinking that is very presence might quell the riots. The mission did not fare well. First, the truck was fired upon by the white mob, which assumed correctly that the Guardsmen were defending the African-American community. Then, as the truck retreated from the white mob and raced into the Greenwood District, it was fired upon by the African-American defenders. They saw its coming heralded by the sound of heavy gunfire and opened fire in self-defense. Despite being caught in the crossfire, the National Guard truck was able to escape without taking casualties or firing a single shot.

As the battle raged, white vigilante squads made “arrests” of dozens of African-Americans who attempted to get out of the city. Luckily, a massacre of those picked up was averted. Seeing crowds of blacks being herded by armed whites, the Oklahoma National Guard stepped in. The Guardsmen took those detained from the hands of the mob, often enough literally at gunpoint. Those rescued were then marched to National Guard holding areas where they could be protected. The wounded were carried to the hospital in the Greenwood District, but then had to be evacuated when the white mob set it on fire.

Air Power Employed

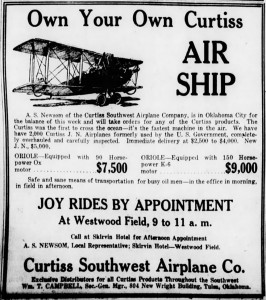

With the attack on Tulsa less than an hour old, a group of pilots from Tulsa’s white community gathered at the nearby airport of Curtiss-Southwest Field. Almost certainly, these were the commercial flight crews working for the Curtiss-Southwest Airplane Company, a firm that had formed a year and a half earlier in 1919 and which, more or less, ran the airport of the same name. Curtiss-Southwest was the nation’s first commercial interstate air freight shipping business, though that honor is usually forgotten due to what they did that day. The company was also a dealer for the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, selling surplus government planes and new models from the Curtiss company to the general public.

Between them, the pilots prepared about a dozen or more light planes. These were surplus World War I Curtiss JN-4 Jenny training planes that had been purchased from the US Army Signal Corps after the end of the war. Curtiss-Southwest had purchased and put these planes to work in its new airfreight business. Other planes were resold by the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to the general public. The US Army sold the planes at a price of $1,500 each and Curtiss-Southwest marked up and resold the planes to willing buyers at a significant profit, charging between $2,500 and $4,000 each. Newly built models that came directly from the Curtiss factory went for $5,000 to $9,000, depending on the type of engine mounted.

Most of the planes that flew that day over Tulsa had served as trainers for America’s military pilots during the First World War. The company, while offering new planes to the public, itself was somewhat underfunded. As such, it flew only surplus, used US Army planes. Most of these had flown at the University of Texas military flight training program at Kelly Field, in San Antonio. Kelly Field had trained over 320 squadrons of pilots during the war. These Curtiss JN-4 Jenny biplanes were the same type later made famous for barnstorming across much of middle America, putting on one-plane airshows and offering rides for a few dollars each.

With the riots in full swing, the pilots at Curtiss-Southwest Field didn’t have barnstorming or their usual oil business flying on their mind. Each pilot took an “observer” on board and, as some reports later claimed, loaded up their planes with balls of fabric soaked in turpentine. Matches were carried to light the incendiary balls on fire before dropping. They took off at 6:00 am, returning and refueling to fly additional missions later in the morning and in the early afternoon.

They employed the turpentine-soaked balls as makeshift “bombs”, or more properly “fire bombs”. With these, they hoped to start fires in the center of the African-American business district. In the first hours, those areas were beyond the reach of the still advancing mob, which was facing stiff defense from the African-American residents. It was a house-to-house fight, battled block by block. The battle was centered on Standpipe Hill, a few blocks from the Mount Zion Baptist Church.

Once aloft, the pilots were guided to the target by the first clouds of black smoke that rose from the outskirts of the area. It didn’t take long for them to fly the short distance to the center of Tulsa and arrive over the Greenwood District. They began orbiting together in a loose formation as the “observers” prepared their turpentine rag balls for the attack. Some of the “observers” also carried rifles aloft, intent on shooting any they saw below. A few carried sticks of TNT, which they lit and dropped as aerial bombs.

One of the residents of the Greenwood District, Mary E. Jones Parrish, was a trained journalist. She later wrote that she and her neighbors heard the approaching roar of the aircraft engines. They looked out the windows of their homes to see what was happening. She then related, if perhaps a bit too poetically:

“…the sights our eyes beheld made our poor hearts stand still for a moment. There was a great shadow in the sky and upon a second look we discerned that this cloud was caused by fast approaching aeroplanes. It then dawned upon us that the enemy had organized in the night and was invading our district the same as the Germans invaded France and Belgium…. People were seen to flee from their burning homes, some with babes in their arms…. Yet, seemingly, I did not leave. I walked as one in a horrible dream.”

One of the planes spotted two men and their wives running across an open field and, swooping low, dropped a hail of lead balls or stones, hoping to kill them. They missed. Two of the four were identified as Dr. Payne and Mr. Robinson — the names of their wives were not recorded. They survived to later testify about the events.

In the hour or so that followed, each plane let loose their loads of these fire bombs from low altitude, setting them alight just before they were dropped. This was a dangerous thing to attempt from inside the cockpit of a wood, wire and fabric biplane, yet they were successful. None of the planes caught fire and burned. They targeted the neighborhoods, business district, and the Mount Zion Baptist Church. Mainly, they aimed for the flat rooftops of the buildings. Once the supply of firebombs was exhausted, those planes that carried “observers” armed with with rifles made low passes over the Greenwood District. They began shooting at any they saw on the ground below. Once out of ammunition, they returned to the airfield for more firebombs, bullets, and fuel.

During one low pass by a biplane, one of the “observers” leaned out to take a shot. He was hit instead by return fire from an African-American sharpshooter. He was either killed by the bullet or died when he fell from the plane to the ground. Ten days later, the event was reported in several newspapers, including the Chicago Defender, which related, “One man, leaning far out from an airplane, was brought down by the bullet of a sharp shooter and his body burst upon the ground.”

Another made a pass and fired at two fleeing boys, who were shunted into a house and brought to safety by an older African-American woman. Hitting a pair of running boys from a handheld single-shot rifle in the cockpit of an airplane flying overhead is no easy feat. The plane did not circle back to shoot again. A second wave of planes returned to drop more firebombs onto the buildings below.

While they may not have had a great effect with their rifles, the firebombing proved devastating. As the flaming turpentine balls fell, many buildings across the Greenwood District were burning out of control. The fire department, held back by the white mob, could do nothing but watch helplessly from a safe distance. As the fires intensified, many of the communities residents were forced to flee their homes, running for their lives as the fires spread from building to building and house to house. These too fell into the hands of wandering vigilante groups who were patrolling the outskirts of the District.

The Mount Zion Baptist Church caught fire after a hail of well-placed firebombs.

Eyewitness Testimony of the Aerial Bombing

In the city center, one of the town’s most prosperous African-American men, a lawyer named Buck Colbert Franklin, who would later prove instrumental in the legal actions that followed the riots, wrote of his experience witnessing the aerial firebombing of Tulsa.

“I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top.”

“Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes — now a dozen or more in number — still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.”

What he described was the volleys of turpentine-soaked rag balls falling on the rooftops of the buildings along “Black Wall Street”. He abandoned his office and made his way through the streets, remarking at the still burning aerial firebombs that marked the way.

“The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught from the top. I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?'”

Another eyewitness, an African-American named Dr. R. T. Bridgewater, who served an assistant county physician, stated that he was “near my residence and aeroplanes began to fly over us, in some instances very low to the ground”. He added that he heard a woman say, “look out for the aeroplanes, they are shooting upon us.”

Later, the KKK wrote of its achievement in an article in a newspaper called, “The Nation”. The writer recounted:

“Then eight aeroplanes were employed to spy on the movements of the Negroes and according to some were used in bombing the colored section.”

The actual number was probably twelve to fourteen planes, but the KKK writer probably didn’t know that. Mr. W. I. Brown, a porter with the Katy Railroad company, arrived to Tulsa with the National Guard. He reported:

“We reached Tulsa about 2 o’clock. Airplanes were circling all over Greenwood. We stopped our cars north of the Katy depot, going towards Sand Springs. The heavens were lightened up as plain as day from the many fires over the Negro section. I could see from my car window that two airplanes were doing most of the work. They would every few seconds drop some thing and every time they did there was a loud explosion and the sky would be filled with flying debris.”

With their stores of fire bombs and TNT exhausted, the planes turned again toward a landing at Curtiss-Southwest Field. Some fanned out into the surrounding countryside, looking for those fleeing the city. One of the biplanes spotted a group of fleeing African-Americans and dove to attack, firing on them with the rifle that the “observer” carried. One man was killed, his name was recorded later as probably Ed Lockard. He died from a bullet to the back of the neck. That attack took place between six and eight miles from Tulsa.

Detention Centers

At the height of the rioting, Mayor Evans and Governor Robertson set up detention centers outside the district to hold those saved from the vigilante gangs of white men. One detention center was located at the Tulsa Convention Hall on 105 West Brady Street. Another center was set up at McNulty Baseball Park, located between Ninth and Tenth Streets on Elgin Avenue. In addition, the old fairgrounds at Lewis Avenue and Federal (Admiral) Boulevard were pressed into service. At these sites, approximately 6,000 African-Americans were detained during the day of the riots and in the days that followed.

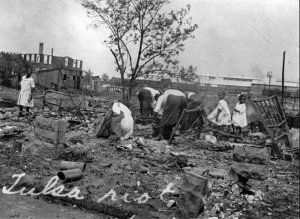

When the day of violence finally ended, all that remained of the Greenwood District and “Black Wall Street” were burnt out neighborhoods. A few stragglers walked amidst the smoking homes and businesses. These too were rounded up by the National Guard. Some of those detained were held for up to eight days — none were ever charged with a crime. On release, they were given identity cards to present in the event that they wanted free passage into white neighborhoods or business districts. On returning to their neighborhoods all they could do was look on hopelessly at the devastation that had been wrought. The Red Cross provided tents and some basic supplies for subsistence.

Aftermath of the Riots

In the aftermath of the burning of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street”, hundreds of African-Americans fled the city and never came back. At the railway station, employees reported that hundreds of one-way tickets were sold. Trains were filled to capacity. Tulsa’s African-American community, which had achieved the American Dream and had built one of the most prosperous communities in the entire United States — white or black — was deeply wounded. “Black Wall Street” would be rebuilt, but it would take years. The scars from that day’s rioting remain to this day.

The story of how it happened, however, was quietly swept under the rug. For decades, nobody mentioned it. It wasn’t taught in schools. It wasn’t acknowledged by the State of Oklahoma or the city. It was only in recent years many in Tulsa learned what happened on that fateful day in 1921 when the city and State reversed positions and published the story.

It seems clear that without the aerial bombing, much of the African-American community in Tulsa would probably not have burned so completely. The damage would have been extensive, but with the firebombing, it totaled an estimated $23 million ($310 million in inflation corrected values). Homes, businesses, schools, and even the Mount Zion Baptist Church had all burned to the ground. The steeple remained and, like a symbol of hope, it towered over the burned out ruin of the streets. In all, 35 city blocks were destroyed and 1,256 residences were burned to ash.

The destruction was staggering — in all, 21 churches and 20 grocery stores were burned as well as two banks, a hospital, the post office (a Federal government building), and more than 600 businesses. Over 4,000 residents were left homeless. The number of dead is still unknown but may have been up to 300 — the Red Cross, which mobilized afterward, claimed that number. Others put the figure at less than 100, though none were as well positioned as the Red Cross to testify on the death toll. Many more were injured.

The devastation was so vast that it wouldn’t be until World War II with the bombings of Chongqing, Berlin, Hamburg, and Tokyo that such damage would be visited again upon an urban area. The makeshift firebombs, as turned out, were extraordinarily effective. During the rioting, homes and businesses were looted and even years later, the effects of that were felt. As the lawyer, Buck Colbert Franklin, wrote: “For years black women would see white women walking down the street in their jewelry and snatch it off.”

In his capacity as a lawyer, Buck Colbert Franklin, the survivor of the riots who wrote about leaving his office amidst the hailstone-sounds of the burning turpentine balls, later took on major role in the rebuilding of the community. Incredibly, just six days after the firebombing, on June 7, 1921, the KKK convinced locally elected city council officials to pass a fire code law that barred the African-Americans from rebuilding their businesses.

Buck Colbert Franklin put his legal training to the task and filed suit, claiming it was wrong. His case was sound. The KKK and other white developers sought to secure the cleared properties for themselves, illegally barring the return of the former residents, since none could rebuild. They had many friends in the courts and most would have given up — but not Franklin. He fought and watched as his case was defeated first in the lower courts. This he had expected based on the influence of the KKK, and next, he battled up through multiple appeals to ever higher courts. One by one, each of the appellate courts, under the influence of the KKK, ruled against him. This was testimony that reflected the hidden power of the KKK.

Finally Buck Franklin filed his final appeal with the Oklahoma Supreme Court. There, finally his case had risen beyond the reach of the KKK. A full review of law and his pleadings on the merits were undertaken. He prevailed completely. The fire code law was declared unconstitutional and stricken in its entirety. With that, the rebuilding of the Greenwood District and “Black Wall Street” could finally begin — it was a process that had taken several years in the courts, itself a victory for the KKK, even if their ultimate goal had been snatched away.

The Pilots and Planes

The pilots and “observers” who flew that day and dropped their homemade firebombs were never officially identified. Almost certainly, they were the very men who flew for the Curtiss-Southwest Airplane Company. They were never arrested, fined, or even sanctioned in any way. Their planes were not impounded either. The Civil Aviation Authorities, the Governor of Oklahoma, and the Mayor simply looked the other way. Although they had not supported the white rioters, they knew not to mess with the KKK. No investigation followed.

The greatest irony came that afternoon when the Tulsa police hired the Curtiss-Southwest Airplane Company to fly an aerial survey of the burning Greenwood District so they could assess the damage. The pilots complied, of course, getting paid to carry police officers over the District to see the very damage they themselves had caused. They got away with murder and massive property destruction — and even got paid afterward to document their evil work.

Today, we can only guess at their identities. They were almost certainly the company pilots. Among many, one pilot appears to be innocent — it seems doubtful that they were led into the air that day by the company’s chief pilot, Duncan A. McIntyre. He was from New Zealand and, as such, was unlikely to have been supportive or involved in any way. He had been previously an expert barnstorming pilot who flew for a time in the Pacific Northwest before moving to Tulsa, Oklahoma. He was not a member or supporter of the KKK.

We know only a few of the other names of the pilots employed at the company. One was John L. Moran — he is listed as an employee in January 1920, in an article that appeared in the Houston Post. Another, W. E. Campbell, was listed in 1919 as the company manager and a pilot. Another man is identified as Mr. B. L. Humphries. He was described as the company president in a newspaper article dating from October 1919. It is unclear, however, if he was a pilot at the time. Another pilot was named Mr. B. Goode. He is cited in the Barber County Index, a newspaper in Kansas, as a pilot of the company in March 1920. Two other pilots, “Happy” Bagnall and Bert Isason are named as working for the company in an article in the Houston Post on February 23, 1920. The others have faded into anonymity with the passage of time. Which, if any, of these men named here participated in the attack is unknown, though the company didn’t have many pilots. Therefore, at least some, if not most of these named were likely to have been involved.

Identifying the individual aircraft that were used is also difficult, if not impossible. In 1921, private aircraft were not yet required to be registered with the civil aviation authorities. That practice would begin in the years after. Even so, those records would show little more than the company name, which we know already anyway. We have no records to identify which planes were involved, such as by manufacturing number. What we do know, however, is that Curtiss-Southwest Field had just 13 planes — all were Curtiss JN-4 Jenny biplanes. One researcher claims that a four-seat, closed cockpit Stinson Detroiter was also at the field, though based on production dates — the first flight of the type was in 1926 — that could not have been possible.

Another plane involved was later identified as owned by the so-called, “St. Clair Oil Company”. More probably, this was the plane of the Sinclair Oil Company. That biplane, also a Curtiss Jenny, was otherwise used for aerial surveys and mapping of the oil fields. Further, the Sinclair Oil Company is known to have provided fuel to the Curtiss-Southwest Airplane Company. Their plane, probably purchased from Curtiss-Southwest, was based at the same field. The only other aircraft within the area was at a nearby field, Paul Arbon Air Field. It was also a Curtiss Jenny. Most likely, however, it did not participate in the attack as there were no reports of any flight activity from that field that day.

That the Sinclair Oil company biplane was employed in the attack is stated in a lawsuit filed two years later. The lawsuit demanded reparations for houses that were burned down (this was the suit that called the owner, “St. Clair Oil Company”). Notably, there were no other aircraft in the area that could have reached Tulsa that day, including private aircraft. Thus, based on the number of planes flying, we can paint a very strong case against the Curtiss-Southwest Airplane Company’s remaining thirteen Curtiss Jenny biplanes and the one plane from Sinclair Oil as being the culprits. Put simply, there were simply no other planes around Tulsa to have flown that day, nor pilots whatsoever.

The lawsuit evidence on the Sinclair Oil plane is plain. Case No. 23, 331 states flatly:

“The St. Clair Oil Company, a corporation, did, at the request and insistence of the city’s agents, and in furtherance of the conspiracy, aforementioned and set out, furnish airplanes on the night of May 31, 1921, and on the morning of June 1, 1921, to carry the defendant’s city’s agents, servants, and employees, and other persons, being part of said conspiracy and other conspirators. That the said J.R. Blaine, captain of the police department, with others, was carried in said airplane which dropped turpentine balls and bombs down and upon the houses of the plaintiff.”

Thus, we surmise that at least one of the city’s police department, a Captain named J. R. Blaine, personally was involved in the attack — if the pleadings are to be believed. His name is somewhat in doubt, however, though a similar name appears in the county records of police officers at the time. Regardless, it seems that at least one police captain served as an “observer” on the Sinclair Oil biplane and dropped incendiaries on the residential areas of the Greenwood District.

That the Curtiss-Southwest Airplane Company’s planes were involved was confirmed further by one of those who escaped the riots, the same African-American woman journalist, Mary E. Jones Parrish. While fleeing the city, she recounted passing an airfield and seeing, “planes out of their sheds, all in readiness for flying, and these men with high-powered rifles getting into them.” There were no other airfields anywhere within 200 miles of Tulsa that had served more than one airplane, nor any others that had hangars, what she called, “sheds” — she could only be describing Curtiss-Southwest Field.

Final Words

Despite all the evidence, there are still those who dispute the use of airplanes to firebomb Tulsa that day. One who has researched the matter extensively is Richard S. Warner. His opinion was formed when he undertook a study as part of an official project funded to research the effects of the riots on Tulsa and what reparations might be paid. He claims that the use of aircraft in the attack is overstated:

“It is within reason that there was some shooting from planes and even the dropping of incendiaries, but the evidence would seem to indicate that it was of a minor nature and had no real effect in the riot. While it is certain that airplanes were used by the police for reconnaissance, by photographers and sightseers, there probably were some whites who fired guns from planes or dropped bottles of gasoline or something of that sort. However, they were probably few in numbers.”

If his claim has merit, the case of Tulsa is interesting — details are many, while the overall picture is difficult to yet completely understand. Aircraft were certainly used and they undoubtedly set many fires. Many reported shooting from the airplanes at people on the ground. Some even claimed that the airplanes turned the tide of the battle; they note that for nearly two hours, the African-American defenders of their neighborhoods had held out successfully. With the firebombing, however, the defense fell quickly and a rout began. Amidst the flames, the citizens of the Greenwood District scattered in the face of the advancing white mob and chased by a dozen airplanes overhead.

Years later, the airport called Curtiss-Southwest Field was closed down and dismantled. Today, nothing remains of the old airfield or its two hangars. The area where it was located is at Apache Street and Memorial Drive in Tulsa. Not even a plaque marks the spot from where the first bombing of an American city was launched.

Sadly, most of the insurance claims filed by the residents and business owners for the damage done were denied at the time. The policies were either not honored outright (probably a sign of racism) or contained riders that exempted damage from what amounted to a “force majeure” event. Predictably, a flurry of lawsuits followed; due to the influence of the KKK, it appears that most were unsuccessful.

In the Tulsa riots, America showed its darkest side. For years, Oklahoma sought to suppress any mention of the riots. It was only in 1996, on the 75th anniversary of the riots, that the state finally included mention of the riots in the official histories. As for Dick Rowland, he was never charged with a crime. He survived the riots under the protection of the Sheriff and lived the rest of his life in freedom. Sarah Page, deeply troubled at the events that were taken in her name, left Tulsa on the train — to where, nobody knows.

Apparently, she never came back.

One Last Bit of Aviation Trivia

The firebombing of Tulsa’s African-American Greenwood District and “Black Wall Street” gave rise to two aviation-related philosophies in the African-American community. The first was espoused by the radical followers of Marcus Garvey. They called for African-American men to train as pilots and prepare for a coming race war. The followers of Garvey believed that a final battle would be fought both in the air, at sea, and on the ground. The vision was simple — if African-Americans did not arm themselves with the latest technologies, they would surely die; the battle to come would be apocalyptic. They saw it as a fight to the death, where afterwards only one of the two “races” would survive. Garvey called for the community to start building battleships, airplanes, and tanks.

The second vision of African-American involvement in aviation was more peaceful in its focus — critically, it was also less expensive. This view was popularized by newspaper writers of popular African-American bureaus, such as the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, New York Age, and Baltimore Afro-American. This approach highlighted the commercial value of aviation and sought to play down the military uses of airplanes. African-Americans should become pilots, in this school of thought, because it would foster social change and drum out stereotypes that blacks were incompetent, unable to master sophisticated technologies, lacked ambition, and were easily frightened. African-American involvement in aviation would bring real democracy to America, so they claimed.

Over time, this second vision won out. The seeds of African-American involvement in aviation were thus planted after the devastation of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Ultimately, this vision would culminate too in the legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. The example set also helped give rise to the non-violence of Martin Luther King, Jr., in the 1960s struggle for equality in America.

For inquiries about the research in this article, contact the author at: tvanhare@historicwings.com.

WATCH THE VIDEO!

+ PLEASE SUPPORT US THROUGH PATREON! +

+ MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION THROUGH PAYPAL! +

My dad is from Tulsa and this was very interesting because I never knew anything like this happened there. I’ve been to Tulsa myself many times to visit my grandparents so knowing this will add interest to the town.

What a fascinating, yet dispiriting piece of history. The meanness of man against man.

A sad and tragic chapter of American history. America’s roots may be watered with the blood of patriots, but those same roots have also received the blood of many victims from the horrors of history — native Americans, African Americans, and a host of other ethnic groups.

Thanks for writing about this. I live up the road from Tulsa in Springfield, Missouri. Springfield too has it’s own dark history. There were lynchings and the KKK. As the “Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave”, one would think that America would have have outgrown this kind of hate. Yet now, look at us. We are again divided and fearful — as before, this time too we are most afraid of one another.

I and my grandson’s were meeting their mom in Okemah today. We arrived early, so we found the Okemah Historical Museum. Upon touring the museum, I was surprised to see displays of Black history. I told my 12 year old grandson about an article I had read about the bombing years ago. A gentleman who worked at the museum overheard our conversation. He said he had never heard about it.

When I arrived back home, I went to my computer to look up the bombing, Your article is so informing. I had forgotten many of the details of the riot and bombing. I was overwhelmed by the inhumanity of this moment in history. Thank you for this thought provoking article. I will encourage my grandsons to read it.

This horrendous massacre of innocent lives and the burning down of an entire community is only part of a wave of repression that swept the country in the post WWI era. A time when the Klan grew from a small, isolated group of fans of the racist epic, Birth of a Nation, to nationwide membership of more than 5 million. Anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, white supremacist, and yet also embracing all-American values such as patriotism, old-time Protestant religion and law and order, many of these people were the self-styled upstanding “good citizens” of their communities.

In Greenwood, it was returning Black veterans who came back from Europe to fight another war — against lynching (a lynch mob precipitated the Tulsa “riots”), discrimination, violence and injustice. They fought, albeit outnumbered and out-gunned, and in return, the white community responded with heightened brutality, burning churches, and shooting innocents. The story of Tulsa is a shameful chapter in our history.

Just six months after Tulsa, another episode of aerial bombing took place in Mine Wars in West Virginia. There, police, paramilitaries and coal company detectives hired private planes to drop surplus WWI gas and explosive bombs on union coal miners in the battle of Blair Mountain. When the U.S. Army intervened, they employed aircraft. On orders from General Billy Mitchell, Army bombers from Maryland were also used for aerial surveillance. One Martin bomber crashed on its return flight, killing the three crew members.

When did Congress state the military aircraft budget between November 1919 and August 1921 that would allow the US military to determine how many aircraft they could sell? Until the military determined the number of surplus planes they were not able to sell any.

Curtis Southwest Air sold D-4s and Waco airplanes in 1918. How is that possible? Waco did not produce the Waco as a saleable aircraft until 1926-Until then the Wacos were a death trap. On June 1, 1921 there are no records of any plane crashes. With that many D-4 Jenneys in the air there would have been plenty of crashes. The D-4 Jenny was extremely hazardous just ask “Lucky” Lindy.

The statement that there would have been plenty of crashes is wrong. If there were several crashes for every several dozen flights, that means the average plane would last about ten flights. And the average pilot would never make it out of training without crashing a plane. Or more. Not very practical in human or economic costs. This is just plain wrong.

I have lived in Tulsa for the last 65 years and always knew about the riot. Heard many versions of what happened on that fateful day. No denying the destruction. The version told to me by my grandfather who was in town that day was that a white man tried to disarm a black man of his pistol when he was shot dead. This prompted the whites to go arm themselves. This led to the gun battle that left many dead.

I have a problem as far as the supposed aerial firebombing. Those surplus aircraft are constructed of spruce (pine) covered in cotton that was made waterproof by doping it with nitrocellulose (liquid gunpowder) . These old planes were oil and gasoline soaked from use. In WW1 pilots carried a pistol not for use in combat but to shoot themselves in case of fire which was their greatest fear. In a time before lighters when matches were used. Ever tried to light one in 90 mph wind? It doesn’t work. I am a pilot and know of no pilot who would allow anything dangerous aboard their aircraft.

This argument makes some points, but is doubtful on some. Gasoline evaporates off pretty quickly. Oil is not easy to ignite unless it is quite hot. Nitrocellulose would be problematic if touched by fire. They could fly a lot less than 90 mph (q is a V squared function). Top speed was actually around 75 mph and stall around 35 mph. They could have slowed to 45 or less for an attack. Lighting would be a problem, but the inside of the cockpit saw nothing like the full force of the wind. It would be very interesting to do tests — very carefully! — to check the practicality of such firebombing. By the way, top speed of a Jenny was 75 mph and stall was 35. They could have slowed to 45 mph or less for an attack.

Whether or not there was an aerial attack, it was still a vicious business from start to finish.

Dan, I could not agree more with you. Today the use of airplanes during the riot is overblown. What was left out of the story is the fact that the U.S. Army did a study of all the buildings destroyed and that all the evidence supports them being destroyed from the ground not the air. The people involved in that study had just been through WWI and had plenty of buildings to study that had been bombed from the air. The characteristics of those buildings didn’t match the ones from Tulsa.

The same people who conducted the studies covered up the event. Can such a government and its reports be trusted to tell the truth without bias? For the surveyors to admit that much of the damage was caused by aerial attack would have implicated the airfield and the pilots. The white washing of the investigation and the event being swept under the rug for 75 years basically answers that question.

How do I subscribe? Is this still online Magazine still publishing?

I begin by saying my husband did not believe me when I told him that there were airplanes that played a part in the destruction of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street”. I googled for a link and came across this video, and I asked him to listen. By that time, he had googled “Dreamland” and one of the survivors spoke about the planes. I listened to this video and found it to be very informative. Thank you for your research. Our history as African Americans, at my age of 57, has become so valuable to me. When I was in school, I guess you can say I was taught lies… just a bunch of lies.