Published on October 24, 2012

The name of Harry Hawker is quite nearly one of the most famous in British aviation history. By the late 1930s, the RAF had settled on two aircraft, the Supermarine Spitfire and the Hawker Hurricane as their single engine monoplane fighter aircraft types. Yet Hawker’s name in British aviation history predates the Hurricane by over 25 years. Harry Hawker, like many in the aviation history, got his start as a competitive pilot in the early days of aviation. In 1912, 100 years ago today in aviation history, Harry Hawker would win his first aviation competition, the British Empire Michelin Cup, which was awarded to the aviator who could set a record for the longest endurance in an aircraft aloft. This is the story of Harry Hawker, a man respected as one of the greatest British early aviators — except that actually he was an Australian.

Harry Hawker’s Early Life

Harry Hawker was born in Australia to a Moorabbin blacksmith on January 22, 1889. Early in life, he saw that his best hope of achieving success was to emigrate from Australia to England. By age 11 at the turn of the century, while still in Australia, he was already working and was learning to become an engine mechanic. Over the next ten years, he steadily improved his skills until one day in 1910, he witnessed the first demonstration of an airplane in Victoria, Australia. Immediately, he set his sights on learning the trade of aviation — and thus took a ship to England to commence his training arriving in 1911.

On arrival in England, he could only secure various odd jobs working in the auto industry. Finally, almost at a point of losing hope and returning to Australia, in June 1912, he managed to shift to the Sopwith Aviation Company, which was in line with his goals. Harry Hawker was employee number 15 in the small Sopwith Aviation Company, which at the time had just one project, building the Howard Wright biplane. For Hawker, it was a dream job. Almost immediately, he commenced flight training lessons, spending almost all of his earnings on aviation — thus, what Thomas Sopwith paid him to work on aircraft engines, he turned around and bought lessons from Sopwith to learn to fly. He proved to be a quick student and in September of 1912 he was awarded his flying certificate from the Royal Aero Club. With this achieved, he was soon recouping his training costs by charging others to learn to fly.

Competing for the British Empire Michelin Cup

Setting his sights on the competition flying, he asked Sopwith to develop an airplane to compete for the British Empire Michelin Cup. Sopwith complied and the team was soon on the factory floor working to rebuild an American aircraft — a Burgess-Wright biplane. The American type was perfect for the competition — it had a twin propeller and it was light with an expansion biplane set of wings, allowing it to fly high, which was the key to Hawker’s winning strategy. With altitude, he could lean the engine considerably, thus extending his time aloft. Still, that wasn’t his only idea.

To comply with the requirements of the competition, the Sopwith Aviation Company made modifications to the Burgess-Wright biplane, adding further features that would enhance its performance for the endurance attempt and also ensuring that every last piece of it was of British manufacture, one of the requirements of the competition. Thomas Sopwith had high hopes for Hawker’s flight, recognizing that setting the record would help expand sales of aircraft made by his small company. While Harry Hawker was a mechanic and not one of the company’s line pilots, he was Sopwith’s own mechanic. Further, he had trained at Brooklands by Thomas Sopwith’s own side. Overall, Thomas Sopwith recognized too that Hawker was a natural pilot. If Hawker could pull it off, Sopwith recognized that the company’s future would be improved.

Hawker’s plan was simple, he would fly the plane to the highest possible altitude and lean the engine to a minimum, then he would pull the throttle back and glide down gently, only to restart and very slowly, carefully climb back to altitude. This way, he would extend the endurance of the plane considerably. Others who entered the competition include R. L. Charteris with an AVRO biplane, S.F. Cody with a Cody biplane, Arthur Knight in a Vickers monoplane, I.G. Vaughan Fowler in a Wright machine and F. P. Raynham in another AVRO biplane — some had already competed in endurance trials, though for Hawker, this was his first event.

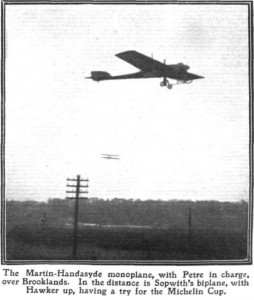

The competition would close on October 31. Hawker was first in the air on October 16, setting an early time of 3 hours and 31 minutes. Twice more he flew over the next week, but each time couldn’t better his time. Then, on October 22, Raynham took off in his AVRO biplane and posted a time of 3 hours and 48 minutes, beating hawker by 17 minutes. By that point, however, Hawker had mastered his climb-glide flight profile and on October 24, 1912, he was ready to prove himself. Somewhat delayed, he only took off in the mid-morning at 9:15 am to begin his long series of climbs and glides. Already in the air was his main competitor, Ryanham, who was off at dawn and already putting good time on his machine.

Soon, as Raynham topped his own record, it became apparent that he was in it for a solid day of flying. He passed the five hour mark and then the six hour mark, even as Hawker was a few hours behind in times. Then Raynham passed the 7 hour mark and it seemed to Hawker that he would be hard-pressed, who had but 5 hours in the air by that point. Finally, Raynham’s 60 hp Green engine suffered a failure when the lubricant ran out. He was forced to land, yet he had set an unbelievable 7 hours and 31 and half minutes aloft.

Hawker could do nothing more than just continue his climbs and glides, hoping for the best. As night rapidly approached, he passed seven hours in the air. Then he passed Raynham’s mark and continued, hoping to put down a time that would be unbeatable. Finally, he could fly no more as the night descended — the competition required that all flying cease within one hour after sunset. Yet on landing, it was calculated that he had smashed the standing record from 1911 (Col. Cody’s 5 hour, 15 minute mark) by nearly three hours, setting a new time of 8 hours and 23 minutes — further, he had beaten Raynham. Hawker’s plane had still not exhausted its fuel. It was a record that would stand for a long time to come.

Aftermath

As for Thomas Sopwith, he immediately made Harry Hawker a test pilot in the company. Soon orders were coming in for his new designs and together, the men advanced the capabilities of the Sopwith types until they became one of the preferred aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps, which placed orders for thousands of planes during the Great War of 1914-1918. The Sopwith Camel would go down in history as one of the finest planes of the war and the plane that shot down the Red Baron (though some Australian ground gunners also claimed the victory).

Yet what goes up must come down, which is the first rule of aviation and one of many rules in business. After the end of the Great War, despite every marketing gambit, the Sopwith Aviation Company faced serious business challenges with the reduction of orders from the military. Above all, even if the company could have downsized and continued, Sopwith was concerned that the British Government would audit their books and charge retroactive taxes for the various wartime contracts the company had held.

By then Harry Hawker and Thomas Sopwith were close friends and business partners. Purchasing the key assets of the artfully bankrupted Sopwith Aviation Company in September 1920, Hawker and Sopwith together formed a new aviation firm, the H.G. Hawker Engineering Company (this was renamed in 1933 to the more well-known Hawker Aircraft Limited). Thus began a string of new aircraft designs — no less than 26 individual aircraft designs over 15 years before the Hurricane was flown in 1935, which made Hawker one of the finest aviation companies in British history.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Although Hawker Aircraft Limited carried Harry Hawker’s name, he never lived to see the flight even of its first design, the Hawker Duiker prototype. In 1921, while flying a Nieuport Goshawk in preparation for an Air Derby at Hendon Aerodrome, his plane caught fire in midair. Hawker managed to extinguish the blaze and crash land, despite severe damage. Sadly, he was killed when his badly burned body was thrown from the cockpit on impact. Sopwith and the others in the company continued in his name to honor his memory.

Today’s Aviation History Question

What was the last aircraft to carry the Hawker name and when was it created?

Hawker 4000, the first flight was in August 2001.

My local aerodrome, commonly called Moorabbin Airport, is officially named The Harry Hawker Airport. after Hawker. He certainly led a fantastic, if short, life.

BTW, the evidence proves that the Red Baron was indeed shot down by Aussie ground troops, not the Canadian flyer chasing him… but then, being from Australia, I’m probably biased.

Our group is commemorating Harry Hawker’s return to Melbourne in 1914 — search online with “Harry G Hawker”.