Published on November 16, 2012

The storm winds were picking up as the French officers yelled to their men to hold onto the lines of the greatdirigible. With 200 men, it seemed that they should have been able to hold it, yet the winds blew stronger. The dirigible, filled with gas, was pulling upward and the anchor lines snapped. The airship’s commander cursed that he had elected to remain overnight in the open instead of walking the disabled dirigible back to its base near Verdun. With a sudden gust, the balloon tore free of the men. A few tried to hold on but quickly let go as the airship twisted away upward rapidly into the darkness. Unmanned, the France’s first great military airship, the Lebaudy Patrie, disappeared into the night skies.

The Lebaudy Patrie

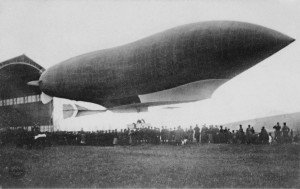

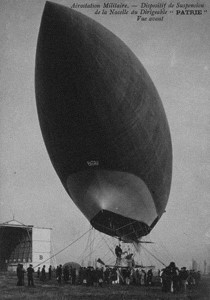

The airship had been France’s first dirigible order. Inspired by developments in England and Germany, the craft was named “Lebaudy Patrie” after the Lebaudy Frères company, which had won the manufacturing contract. The first flight took place today in aviation history, on November 16, 1906, and lasted 2 hours and 20 minutes — a rather lengthy test. A month later, the airship was transferred to the French Army and began undertaking aerial trials from its first base at Chalais-Meudon near Paris. So successful were these that the great airship was the pride of early French aviation in a time when French fixed wing, powered aircraft were still in their infancy. Nonetheless, there were early problems with handling and reliability including problems with the propeller.

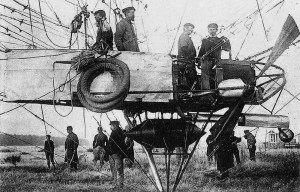

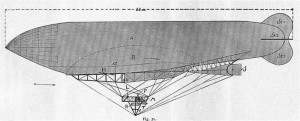

The Lebaudy Patrie could carry a crew of four to six men in an open gondola of nickel-steel tubing that hung 11 feet beneath the gas bag. The equipment, as reported in the magazine Progress, included “a ‘siren’ speaking trumpet, carrier pigeons, iron pins, ropes for anchoring the airship, a reserve supply of fuel and water, and a fire extinguisher.” With this the crew could also carry between 30 and 50 bombs of 10 kg each; these were called “torpedoes” by the designers. Fully loaded, the airship could climb to 4,000 feet of altitude, well out of the range of small arms fire and, in an age without high altitude anti-aircraft artillery or combat aircraft, it was considered immune from enemy threats. It also had a mounting for a powerful searchlight that could illuminate the ground below for night reconnaissance from the air. A wireless telegraph system rounded out the equipment on board.

After nearly a year of tests, in late November 1907 the Lebaudy Patrie was deployed to the border regions of Germany, to be based at Belleville-sur-Meuse near Verdun where a large hangar had been constructed. The flight there required 6 hours and 45 minutes to complete and was done at an average speed of 22 mph. If there was to be war, the French military reasoned, it would be here that the harshest battles might be fought. She was ready for her first patrol on November 29, 1907. With little fanfare, the great airship was led out of its hangar, a huge building with wind doors to protect the craft within from the weather. It was prepared for flight as a crowd gathered. The crew mounted the airship and were soon underway — it would be her first and last flight from Verdun.

The Storm of November 29, 1907

The flight out on November 29, 1907, went well until one of the aircrew accidentally got his shirt caught in a drive gear, which seized the engine and propeller. Unable to make way, the airship was brought down carefully. It landed near the town of Souhesmes and soon a French Army unit with 200 men and officers was dispatched to the site. The commander had a simple choice, he could walk the airship back to Verdun, dragging it by its ropes, or overnight there while repairs were made. He chose the latter option given the distance involved — it would have been nearly 9 miles walking to the northeast to reach Belleville-sur-Meuse, a questionable endeavor to complete before nightfall.

However, that night disaster struck. A storm moved in and gripped the balloon even though was tied down. It was exposed and in the open, near a small wood. Without the protection of the hangar, there was little the men could do. The commander wanted to let off gas and partially collapse the dirigible’s gasbag, but the release valve rope had not been fitted prior to departure. There was no way to deflate the airship. The commander realized that this was a disaster in the making. With a final gust, the airship tore free of the grip of the 200 men holding it and soared upward, moving away rapidly toward the northwest carried by the high winds. There was nothing the men could do but watch. Without the any crew on board and stripped of her ballast (over 1,700 pounds removed in ballast weight), later estimates were that the airship initially rose to an altitude of approximately 6,600 feet. In any case, anything above about 8 or 9 feet was out of reach for the men on the ground.

The Strange Journey of the Lebaudy Patrie

Unmanned and blowing in the wind, the airship was carried aloft over the northeast corner of France. For the next few days, there was no news of any sighting of the airship at all. It appeared that she was lost. The manufacturer was asked what might have transpired. The response wasn’t encouraging — the gas would slowly leak off, causing the airship to descend and ultimately come to the ground. Yet where? The French military worried that the shifting winds might have carried the ship into Germany and into “Prussian hands”. The press carried the stories of worried military generals and asked the public to report any sightings.

Soon, telegraph reports were received from around Europe and even from as far away as the United States with claims that the airship had been seen. Few were credible, but each was evaluated. Then more conclusive word was received from the United Kingdom. A confirmed sighting was relayed that dated from the morning of Sunday, December 1. The airship had been seen drifting over Cardigan in Wales — nearly two days after its loss during the night. Where had it been in the meantime? Clearly, it must have floated over the English Channel and across England, yet none had seen it. Perhaps much of that journey had been during the night of the storm.

Another report was received that dated from in the late afternoon of that same day. The airship had been conclusively spotted moving smartly along with the wind at Ballysallagh, near Holywood in County Down up in Northern Ireland. There it had descended and struck the ground with some force. The jar of the impact had sheared off the propeller and bevel gearing that connected the engine drive shaft to the prop shaft. With the heavy weight of that equipment torn free, the airship had risen once again to altitude and was last seen as it continued to move off to the north.

Another report was telegraphed from Lloyd’s of London, which reported that its signal station at Torr Head along the Antrim coast spotted the airship in the evening. She was headed northward out over the sea. The next sighting was from an offshore island off the coast of Scotland. Finally, a telegraph message was received that confirmed as the final sighting of the Lebaudy Patrie. She was drifting over the sea as seen from the steamship Olivine while underway. Its captain reported this last sighting at latitude 58 degrees North, off the Hebrides.

After that, she was lost completely and no trace was ever found.

Next Steps for France

Despite the loss of the Lebaudy Patrie, the French military’s confidence in airships was not shaken. A second airship was ordered — a sister ship to the Lebaudy Patrie that was christened “République” and some months afterward, in August 1908, a third airship was ordered as well, this one was to be christened “La Liberté”. By then, France was beginning to evaluate fixed wing, powered aeroplanes for military uses — as was Germany. These new aeroplanes soon became the primary focus of the military. Just five years later, the two nations would enter into a dark conflict that would later be known as World War I, in which air power would finally come of age.

One More Bit of Aviation History

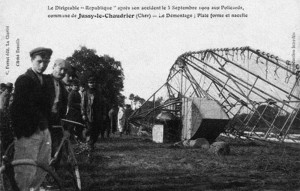

The sister ship of the Lebaudy Patrie, the “République”, suffered a terrible fate just a year later in 1909. While en route to Chalais-Meudon during the morning on September 25, near the Château of Avrilly, one of the propellers on the “République” sheared off and punctured the gasbag. The tear was huge and the great airship lost gas rapidly. Out of control, she plunged earthward with terrific speed. On impact, the crew of four were killed — Capt. Marchal, Lt. Chauré, and two “Adjudants mecaniciens” named M. Vincenot and M. Réau. After the crash of the “République”, the French military and public finally lost faith in airships and elected to pursue fixed wing, powered aeroplanes instead, a decision that would set the stage for the coming conflict of World War I.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Non-rigid airships competed with rigid airships — in Germany called Zeppelins — for many years. Finally, with the crashes of the Hindenburg and the US Navy’s own Shenandoah and Macon, it seemed that the era of great airships had come to an end. Yet this wasn’t true, at least not for non-rigid airships — indeed, what was their finest hour thereafter?

The finest hour of the non-rigid airships (a.k.a. blimps) came during World War II. They flew escort to merchant and military ships to protect them from attacks by German U-boats. Not a single ship was lost while being guarded by the U.S. Navy blimps. Only one blimp (the K-74) was lost in combat when it engaged a U-boat. The blimps contributed to the capture of at least one U-boat and the sinking of a few more.

Convoy escort and anti-submarine patrol in WW2.

And we are making Zeppelins again today for military use!