Published on February 3, 2013

By Thomas Van Hare

Today in aviation history, on February 3, 1959, a small plane crashed in bad weather near Clear Lake, Iowa. Every year, there are many plane crashes, but this one is remembered because on board were three of the greatest names from early Rock & Roll — musicians Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J. P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, as well as the pilot, Roger Peterson. Yet few know the full story of what really happened that night all those years ago when a chartered plane crashed in bad weather into the corn fields of Iowa.

The Tour and the Charter

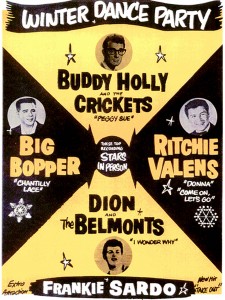

In late 1958, Buddy Holly had just split with his previous band and had assembled a new group. Together, they were off on a concert tour called the “Winter Dance Party”. Ritchie Valens and “The Big Bopper” were along to promote their own new brand as rising stars of the new musical genre. They were scheduled to visit 24 cities that stretched across the winter-bitten Midwest in a tight schedule that spanned just three weeks — slightly more than one gig a day.

The three rockers could have gone on the tour’s scheduled band bus. However, to save money, they had hired a cheap bus and conditions on board were terrible. When the weather was bad, riding on board was a grueling experience, worsened by haing so many concerts packed back-to-back in such a short time. Many members of the band were sick with the flu, one had even come down with frostbite from the cold.

That fateful day, after finishing a gig at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, Buddy Holly decided that some of them should take a small charter plane ahead to their next concert stop, in Fargo, North Dakota. The nearest airport to find a plane was at Moorhead, Minnesota. Taking a flight would get them to Fargo faster, giving them some much needed time to rest, but would keep them off the nightmarish band bus, and giving them hope that, with an early arrival, they could find a laundromat to clean their dirty clothes.

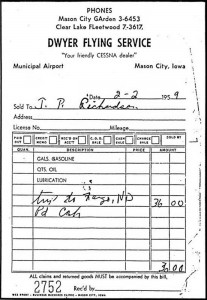

On Holly’s request, the owner of the Surf Ballroom chartered a small plane for them through Dwyer Flying Service, which flew from the local airport, Mason City Municipal. The plane would seat a total of four, including the pilot and each passenger would pay $36 for a seat. After some discussions and a coin flip to see who would get the chance to fly instead, the “winners” of the coin toss drove to the airport. Ominously, a light snow was already falling late in the evening on February 2, 1959.

The Pre-Flight

Arriving at the airport around midnight, the three musicians met with the pilot, 21 year old Roger Peterson. The plane that Peterson was to use for the flight was a Beechcraft Bonanza 35 (V-Tail), a light, single engine airplane that was a popular choice for higher end private pilots. Its registration number was N3794N. While for decades a persistent rumor maintained that the name of the plane had been, “Miss American Pie”, that appears to be little more than a rumor. In any case, the real meaning of American Pie was revealed with the sale in 2015 of the notes and original hand-written lyrics by Don McLean, who commemorated the crash in his famous song — it turned out to be poetic shorthand for “as American as apple pie”. As a plane type, Beechcraft Bonanzas weren’t all that much more complex than a run-of-the-mill Piper Comanche or a typical Cessna 210, though they were faster. They also had some unique flight characteristics.

What happened next is still debated. The best assessment of the terrible events that followed can be drawn from the post-accident crash investigation. Most certainly, Peterson checked the weather prior to departure, as the records clearly attest. Further, he could see with his own eyes that the field was in light snow. The key question was what were the conditions aloft? He asked the right questions of the weather briefer but amazingly, the briefing he received was still incomplete. It left out a number of key details including the terms “deteriorating conditions along their route of flight.” The briefer also neglected to mention that there were several Flash Advisories that indicated heavy icing along the intended route.

The weather conditions would have been challenging even for a commercial airline pilot, yet Peterson was left uninformed and without key information that might have made him abort the flight or adjust his plan. He might have delayed his departure to observe the conditions, for instance, but the FAA weather briefer’s mistake was the beginning of a tragedy that was all too avoidable.

Had the full weather information been known, it is quite possible that Peterson would have recognized that he would have had to fly on an IFR flight plan. As such, he would have elected to not fly that night. The owner of Dwyer Flight Services, Hubert Dwyer, was a highly experienced commercial pilot and also attended the briefings — and nothing reported by the weather briefer was particularly alarming to him either. As it was, conditions at Mason City sounded viable — a 6,000 foot measured ceiling, visibility 15 miles plus, temperature of 15 degrees F, dew point of 8 degrees, winds were from the south at 25 to 32 knots; the altimeter setting was 29.96 inches…. It sounded all pretty typical for Minnesota’s usual winter evening. Shortly after the briefing was completed, the weather was updated to report a ceiling of 5,000 feet in light snow with an altimeter setting of 29.90 inches.

Peterson had 711 hours of flight time, including over 100 hours in the Bonanza.

The Flight and Crash

At 12:40 am, the three passengers arrived at the airport. Quickly, their baggage was stowed on board the plane. At 12:50 am (in the early morning hours of February 3), the pilot, Peterson, taxied toward Runway 17 after telling Hubert Dwyer, the owner of Dwyer Flight Services, that he would file his flight plan once airborne. While taxiing out, he called for updated weather. What he received was a report that conditions had not changed materially — yet another major error by the FAA weather briefer. In fact, the weather had deteriorated markedly to a 3,000 foot ceiling with visibility 6 miles in light snow and winds from the south at 20 knots. Further, the winds were now gusting to 30 knots. The altimeter setting had gone lower to 29.85 inches.

Unaware of the increasingly challenging weather conditions, Peterson took off at 12:55 am. Once airborne, he made a crosswind turn and climbed to 800 feet before turning to the northwest. Departing the airport area, he found himself unexpectedly in what pilots commonly call, “hard IFR”. With the sparse population of the central Midwest offering few if any lights on the ground at that late hour and with a solid overcast obscuring the stars and Moon, he had no outside visual cues whatsoever. Pilots describe this as the equivalent of painting the cockpit windshield black. Predictably, he lost his bearings and orientation.

Instead of the more common Attitude Indicator (Artificial Horizon) that Peterson had trained with and flown for most of his short career as a pilot, the Beechcraft Bonanza he flew that night was equipped with an unfamiliar type of attitude instrument, the Sperry F3 Attitude Gyro. This type of AI apparently confused Peterson. A Sperry F3, as bizarre as it might sound to those familiar with modern AI instruments, actually shows the plane from the reverse angle, with the horizontal “horizon line” going up to indicate a climb, rather than lower, as an artificial indication of the sight picture of the horizon. Thus, Peterson probably thought he was climbing when he was diving. Nonetheless, he should have seen the altimeter winding down quickly, though at only 800 feet of altitude, there isn’t a lot of time to sort out what probably would have appeared to be instrument errors.

The best guess of what happened is that Peterson got completely disoriented and began a steady descent, thinking he was in a climb. Most probably, he slowly drifted off into a right turn and, spotting the altimeter reading winding down, he pulled back on the yoke to raise the nose. As a result, he entered into a classic right hand “death spiral”. While he thought his wings were more or less level, in fact, he was actually in a hard right turn. Seeing the altitude dropping even faster now, he pulled back even harder on the control yoke in an attempt to recover from the dive. However, this only further steepened the turn, increasing the rate of descent rather than pulling the plane out of its dive. Had he leveled the wings first, he could have pulled out easily — but again, from only 800 feet of altitude, there isn’t a lot of time to work things out. Instead, it appears that that Peterson simply spiraled down into a crash, never fully comprehending the confusing instrument readings that showed him nose up. He probably never realized that he was in a tightly-wound death spiral.

The plane hit the ground at a speed of approximately 170 knots. The right wingtip hit first with the plane in a shallow dive. Instantly, it cartwheeled into a pile of twisted wreckage, killing all four men on impact. The bank angle was estimated to have been nearly 90 degrees — quite literally flying sideways to the ground. Peterson, in his efforts to pull out of the dive, was probably pulling more than 4Gs. The rate of climb/dive indicator was jammed in place from the impact. It showed a descent rate of 3,000 feet per minute.

From the ground, observers saw the Bonanza head to the northwest. Then, they observed the flashing tail beacon as the plane descended toward the ground in the distance. It disappeared below the horizon line. Just five minutes after departure, Air Traffic Control tried to radio Peterson. They got no reply. As well, Peterson never filed his flight plan from the air — the flight ended that quickly. Later, there was no call in at the time of his projected arrival at Fargo — it was only based on that missed call that was declared to have “gone missing”. Hubert Dwyer feared the worst.

Aftermath

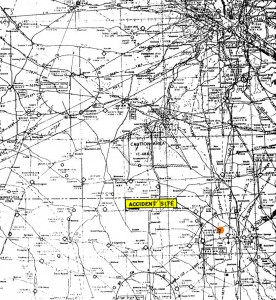

The following morning, the owner of Dwyer Flying Service, Hubert Dwyer, took up his Cessna 180 to search for the missing plane. He had no news of Peterson’s arrival the night before and was very worried about what might have happened. He had seen first hand how the bad weather had developed overnight. As it was, Dwyer did not have to fly ery far. From the air, just five miles from the airport, he spotted the wreckage from the crash — the time was 9:35 am on February 3, just under 9 hours after Peterson had taken off.

The remains of the plane were twisted and thrown up against a farm fence. When first responders reached the scene, the bodies of the three passengers were lying in four inches of fresh snow — one had been thrown 40 feet from the plane. The pilot was still strapped into the cockpit seat. Parts of the plane were scattered over a distance of 540 feet across the snow.

During the investigation that followed, it was determined that Roger Peterson, the pilot, was not yet certified for Instrument Flying. In fact, in the days before the flight, he had failed his instrument check ride. Nonetheless, he had taken off that night expecting to be flying a VFR commercial flight with some light snow — it was completely legal to do so based on the weather briefings he had received from the FAA. He undoubtedly expected an easy winter nighttime flight based on what he had been told. Indeed, he would probably have been fine if those were the conditions he encountered. Instead, the weather briefing system had failed him — he ended up in solid instrument conditions right from the start, conditions which he would have never attempted. Being not fully trained in Instrument Flying and being unfamiliar with the Sperry Attitude Gyro, his situation was especially dire.

In the end, three of the greats of early Rock & Roll history died that night, along with the pilot, Roger Peterson. Buddy Holly was just 22 years old and Ritchie Valens was only 17. J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson was the oldest, at just 29 years of age. The flight was a tragedy that changed music history. As for the weather briefer who failed to provide an accurate and complete briefing, it isn’t clear if he was ever censured for his actions that night — based on the official reports, it appears that he was not reprimanded.

==> Click Here to Read the Original Accident Report (PDF)

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

One of the most famous songs in Rock & Roll history is “American Pie” by Don McLean, which was written about the crash that night. Yet this isn’t the first (or only) song written about the loss — what other song(s) were written and by whom?

Also recorded on Revolution album by hard rock band Slaughter, penned by Mark Slaughter & Dana Strum.

Don McLean’s website says that the plane was NOT named “Miss American Pie.” Do you have a citation for the name?