Published on March 23, 2013

“ACCORDING to reports that have reached us, MM. Marc Pourpe and George Verminck, two Bleriot pilots who have been giving flying exhibitions in Ceylon, have been rather severely handled by the Government authorities there. It appears that they were given permission to carry out their flights at the Colombo racecourse on the understanding that they confined their flying to the immediate neighbourhood of the ground. This they did not do, and so the trouble arose.”

So read a report published in the Royal Aero Club’s newsletter, Flight, that published 100 years ago this week regarding what should have been an excellent experience by two French pilots visiting to the faraway lands of Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka and located off the southern tip of India). The problems began when the pilots actually flew — much to the surprise of the governors who had issued them permission to do so. The pilots were then accused of aerial spying — in those early days of aviation, it seems that the dangers of flight were sometimes more political than scientific.

The Suspect Flights

As it happened, the entire affair was purely a misunderstanding — the two aviators had paid little attention to the restrictions on where they could fly. Of the two Marc Pourpe (French pilot certificate 560) was more experienced than Georges Verminck (certificate 1084). They should have known better — in any case, the report in Flight continued:

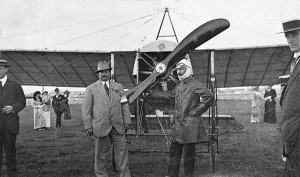

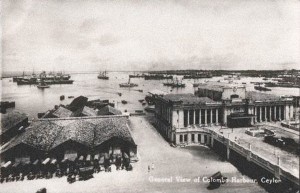

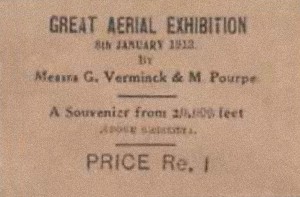

The flights that MM. Pourpe and Verminck made on December 10th last constitute the first real flights that have been observed by the public of Ceylon. Despite the wind, M. Marc Pourpe ascended on his 50-h.p. Gnome-Bleriot “La Curieuse,” and flew two circuits. His second circuit took him well outside the boundaries of the ground in the direction of Bambalapitiya. The flights — for M. George Verminck flew as well on his two-seater Bleriot — were well received. No criticism was made, however, of the fact that both men, M. Pourpe especially, had paid little heed to the understandings under which they were permitted to fly. Perhaps it was in some measure due to this that, the next day, M. Poupre, giving an exhibition flight, circled once round the ground and set off towards the sea. Returning, he passed over the harbour and the forts, on Galle Face and Galle Buck.

Soon after he had landed he was met by the superintendent of police and the conversation that ensued undoubtedly had reference to M. Pourpe’s breach of agreement. Later, the aviators were informed that they were to make no further flights until the matter had been fully considered by the Governor.

The Investigation, Search and Fines

In near complete ignorance of aircraft and aerial reconnaissance — much less spying — the authorities then proceeded to search for cameras and other evidence, impounding the two aeroplanes and searching their flight gear.

While we have little sympathy with anyone who so deliberately commits a breach of faith, we cannot help thinking that the authorities might have gone to work in a less antagonistic spirit. From reports, it seems that the police placed the aeroplanes “under arrest,” for a military officer in mufti was put on duty at the entrance of the tent hangar. Meanwhile, inside, the superintendent of police conducted a minute examination of the machines to determine if any cameras were concealed about them. The police even went to the extent of turning M. Pourpe’s aviation suit inside out in their search for evidence. Nothing was found in the hangar, however, but the police seized two cameras and some two dozen plates belonging to the aviators. They were developed and found to be nothing more serious than the usual collection of views that travellers obtain going from one place to another.

A fine of sorts was then levied — essentially just keeping the deposit the pilots had made to qualify for receiving official permission to fly:

Further, the police informed M. Pourpe that they would retain the 1,500 rupees that he had deposited as a guarantee that he would make good any damage that might be done to public property. Taking things all round, M. Pourpe was indignant — indignant that his deposit was to be retained, and indignant to think he was being regarded as a spy. He remarked that when he flew over the Channel and landed at Dover he saw the whole of the Harbour and Dover Castle from above. But he was treated in a most cordial fashion by the officers stationed there, and they even started up his propeller for him the next morning when he resumed his flight.

A resolution was sought by appealing to higher authorities — a strategy that worked perfectly.

Eventually, MM. Marc Pourpe and George Verminck called on the Acting Colonial Governor, Mr. L. W. Booth, and gave a satisfactory explanation of their conduct. Their explanation was accepted by His Excellency the Governor, and they were given permission to resume their flights on signing an agreement which clearly defined the districts over which they were not to fly. M. Pourpe, when interviewed afterwards by a representative or the Ceylon Observer, remarked that when they arrived at Colombo they were given permission to fly. The authorities could not have done otherwise. How could they prevent flying? “There are certain places over which we are not allowed to fly” M. Pourpe said,” but I have never seen Colombo mentioned in the list at all. If they had told me it was a fortified place I give you my Word of honour that I would never have gone.”

Aftermath

It is worth noting that in that era, the “great powers” were truly suspicious of each other. Indeed, a war was not far off — just a year away. Nonetheless, to imagine that the British holdings of Ceylon would have had strategic importance was overstating more than a bit. As for Marc Pourpe, he did his best to explain it all away and point out that he was within his rights.

He produced his pilot’s certificate which, as everyone knows, bears the following request in the English, French, German, Spanish, Russian and Italian languages: “The Civil, Naval and Military Authorities, including the Police, are respectfully requested to aid and assist the holder of this certificate.”

“I showed my certificate to the authorities when I arrived,” he said, “and they saw how it was worded. Instead of doing what they did, they ought to have helped us.”

Given the tone of the article, it appears that Flight certainly agreed.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Did aircraft play any role during World War I or later in World War II over Ceylon?

An accurate story.