Published on March 31, 2013

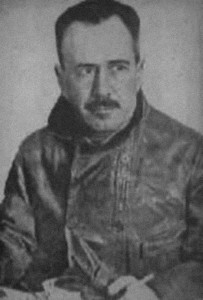

With 650 miles yet to go, the winds had not turned in their favor. The two Portuguese aviators, Sacadura Cabral and Gago Coutinho, computed that they had just 8.5 hours of fuel remaining, and they were still burning 20 gallons per hour. To make it to the rocks called the Penedo de São Pedro, they would have to fly at an average ground speed of 80 mph, yet they were only at 72 mph. Disaster loomed.

The pressure to continue was immense, since the news of their crossing was being covered in the newspapers around the world, but most of all within Portugal itself. They pressed on, despite the risk, hoping that the winds would improve. After a time, they realized also that if they were to ditch in the ocean, any rescue would be unlikely. Searchers would assume that they had flown another 90 minutes based on the amount of fuel that they had reported — thus the search would commence nearer the rocks than they were. Yet to succeed meant more than their lives to them — it meant that their goal of proving that flying could be done for long distances over water without reference to land, would have failed.

The Disaster at the Rocks

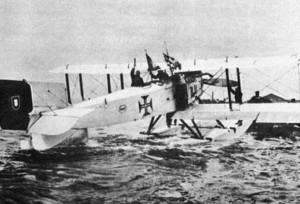

Incredibly, they made it to the rocks of Penedo de São Pedro, though they had less than a gallon of fuel still remaining in their fuel tanks when they touched down. The naval cruiser awaited their arrival, just as planned — it would have gone well, but the seas were running rough with high waves. There was no shelter at these small rocks that measured 200 meters long and 15 meters in height. They tried to take some cover from the wind-blown waves behind the cruiser, but the seaplane was overwhelmed quickly because of the partially flooded twin floats. Their Fairey IIID, the “Lusitânia” was lost.

Even so, having successfully navigated the route, they had proved the key point — that over water flights of such distances were possible. In fact, they had proven the navigation points perfectly, finding the tiniest rocks amidst the open ocean after 11 hours and 21 minutes of flight. The news of the navigational achievement stunned all of Portugal and many others around the world — even having lost the seaplane, they were declared heroes.

The Second Great Disaster

The Government of Portugal knew at once that the flight had to continue. Without delay, they crated and shipped another of the Fairey IIID hydro-aeroplanes to join the two men at the rocks. In the meantime, the men rested on board the NRP República. When the new plane arrived on board the ship, the seas remained too rough to lower it into the water. Together, they continued on to Fernando de Noronha, several hundred miles beyond. The NRP República and the other vessel arrived together on May 6. After a few days, the seaplane was lowered into the waters and the aviators decided to take off from Fernando de Noronha, fly back to the Penedo de São Pedro, and then return again, so that the entire distance from Portugal to Brazil would have been spanned by air.

It might have worked too if the second aircraft, christened the “Pátria” hadn’t encountered a major storm as it neared the rocks soon after it left on May 11. As they flew toward the rocks, conditions worsened and eventually were so bad that Sacadura Cabral turned back early, leaving 15 miles of the leg unfinished. Working his way back to Fernando de Noronha, he and Coutinho were soaked in the open cockpits. Further, the plane was not designed for rain. The fuel was becoming contaminated with water. They pressed on, heading back but after nine hours of flight, but the engine failed them. They landed the seaplane in the open ocean, far from land.

For several hours, they tried to get the engine started but to no avail. Finally, they succeeded, though they could not get enough power to take off. With no other options, they motored westward, hoping to make it into one of the sea lanes that were closer ashore, though as night fell, the plane was taking a beating from the waves. The tail was being hammered and finally, with the engine again dead, Cabral sat on the front of the plane to hold the tail higher. Both Cabral and Coutinho could see, however, that the floats were slowly filling with water. The plane was slowly sinking. Sacadura Cabral describes what happened next:

“The floats are submerged and hydro-aeroplane will not last long…. At 23:45 I spot a light by starboard tack. It’s a ship, there can be no doubt! I fire off two shots with my flare gun, signals that that are matched immediately.”

Though he didn’t write it, Sacadura Cabral could just as well have written, “We are saved!” The British ship “Paris City” of the Reardon Smith Line, having received a general radio message asking assistance, had deviated eastward out of the shipping lanes in hopes of spotting the plane. The ship’s captain, A.E. Tamlyn, hoped for a lucky chance — he was sailing a long voyage himself, from Cardiff to Rio de Janiero. It was perhaps the best decision of his life.

Even if the “Paris City” took the Fairey IIID in tow, the damage done was significant. In the morning, the NRP República met with the Paris City and attempted to winch the plane aboard. Sadly, the second of the voyage’s specially made seaplanes broke up and fell away into the water. All that could be saved was the engine.

The Third Plane

Given the high priority and extraordinary press coverage of the events, the Government of Portugal crated and shipped the third and last of the three Fairey IIID hydro-aeroplanes. Yet another Portuguese Navy cruiser, the NRP Carvalho Araújo, a sister ship to the NRP República, was sent out on the mission. The third plane was christened the “Santa Cruz” by the wife of Brazil’s president. Thankfully, the remainder of the voyage was largely along the beaches and shorelines of Brazil. No long legs over water were to be flown, no great navigational challenges remained. Barring any unexpected twists, this third plane would make the trip the rest of the way to Rio de Janiero.

It was June 5 before the two men finally took off in the newly arrived third plane, the “Santa Cruz”, to continue on to Recife. They managed it in 4 hours and 30 minutes at an average speed of 67 mph, covering 300 miles. Touching down in the water at Recife, they had finally linked the two continents — Europe and South America — and had done it for Portugal, proving that nation’s once great navigational prowess remained as strong as it had been in the Golden Age, when Portuguese ships had circumnavigated the globe and opened passage to the Far East.

The two men took the “Santa Cruz” down the coast of Brazil, enjoying receptions at each city along the way. Finally, on June 17, at 17:32, they touched down at Rio de Janiero, completing a trip that was, at that time, the longest over water navigation challenge in aviation history. The celebrations triggered by the success of their flight swept all of Brazil and Portugal, together in the glory of the two men who had done what had previously been thought impossible. Amidst receptions, champagne and many honors, the two aviators were greeted seemingly by every dignitary in Brazil.

Final Thoughts

In the end, the total flight time required to make Rio de Janiero was 62 hours and 26 minutes. Along the way, the two Portuguese Naval officers had gone from Lisbon to Las Palmas, Gando, S. Vicente, S. Tiago, Penedos de S. Pedro e S. Paulo, Fernando de Noronha, Recife, Salvador, Porto Seguro, and finally to Rio. In all, they had flown 8383 km. To Gago Coutinho’s credit, he never once failed in a single navigational challenge, bringing the plane perfectly to wherever Cabral asked.

In the eyes of the Portuguese, thus, it was not Sacadura Cabral who was to be celebrated the highest, even if he had been the pilot — no, that honor would fall rather unexpectedly upon Gago Coutinho’s shoulders, the greatest navigator in aviation of his day.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What famous aviator was inspired by the Portuguese flight to attempt his own crossing less than a decade later?

I don’t wish to be ungracious, and I’m sure that by the standards of the day, these aviators were considered very brave. But with that said, professionals are expected to manage risk better than just hoping a tailwind will magically appear.

Also, the time to learn that the floats leak like sieves, or what the fuel consumption really is, or how much fuel yon really need to make a trip with at least a little reserve, or that the fuel tanks admit rainwater or that when the plan goes to hell, you turn back and save the plane are all things that are expected of professionals.

Presumably the reason for this trip was to encourage civilians to fly long distances over water. I submit that losing two aircraft to finally finish the trip in a third aircraft, even with help from the navy, would not encourage most rational people to buy a ticket. Sorry, but this just ain’t they way it is supposed to be. First do the homework, then do the flight, while making it as normal, safe and generally boring as possible. Seal the floats and seal the fuel tanks and enlarge them by maybe 100 gallons, and everything would have changed for the better, no space age materials or skills required, just a little thought and planning.

The success of the flight was widely noted — it inspired others, including Charles Lindbergh to attempt long range, over water navigation. While by today’s standards the two Portuguese aviators risked too much too many times, it was by such things that the very standards you hold up were developed. It is human nature to learn best from mistakes. The sad part is that aviation does not tolerate many mistakes — “better safe than dead” is the rule, much more than “better safe than sorry”.