Published on April 8, 2013

Mario de Bernardi was the epitome of the Italian aviator, dashing, smiling, confident and — above all — daringly fast. Born in the small town of Venosa, Italy, in 1893, he first joined the Italian military in 1911 at the age of 18 to serve in the cavalry. Soon thereafter, he transferred to the new Air Service where he was assigned to an airfield near Verona and flew with Italy’s 91st Fighter Squadron. Credited with the first kill by an Italian aviator during the Great War, he amassed a total of four confirmed victories by the end of 1918, though his personal count was five, with the last being unconfirmed by the authorities. After the war, he de Bernardi was assigned by the Italian Air Service to its racing division. He would spend the next nearly two decades as a test pilot, racing pilot and international aerobatics competitor for Italy.

If there is one thing to remember about Mario de Bernardi, it would be his extraordinary flight in the Schneider Cup seaplane races in 1926 racing in a Macchi M.39 seaplane. For both the dashing young aviator and for Italy, it was their finest hour of the 1920s.

The Schneider Cup

In 1926, Major Mario de Bernardi was one of only a handful of the top Italian pilots assigned to the seaplane racing program. By the mid-1920s, the Schneider Cup seaplane races were hotly contested as many nations in Europe, as well as the United States, competed to demonstrate their engineering and aviation prowess. Their goal was to build and fly the fastest seaplanes in the world. In 1926, the Schneider Cup was held at Hampton Roads, Virginia, as the Americans had won the Cup in 1925 off the Lido Beach at Venice, Italy — a victory achieved by Jimmy Doolittle. For Italy, after that defeat, it was a matter of pride that the Cup be brought back to Rome.

In the rules of the Schneider Cup, if any nation won three years in a row, the competition would be considered completed and the trophy would remain in the victor’s country for all time. Italy had nearly won the cup already, winning both in 1920 and 1921, with excellent runs off the coast of Venice at Lido Beach. The third year, however, in 1922, a British pilot won in his Supermarine Sea Lion II. The two years thereafter, shockingly, were taken by the Americans. With the third win now looming, the Cup was in danger of being forever placed into American hands.

Prelude to the 1926 Race

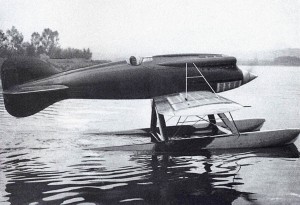

For the races of 1926, at Hampton Roads, Italy geared up to win. No expense was was spared in the development of Italy’s fastest plane, the all red Macchi M.39. The plane was designed by Mario Castoldi around the narrow profile of the 800-horsepower FIAT AS.2 liquid-cooled V12 engine. Numerous technical advances were built into the plane. Among the most innovative features were that the left wing was longer than the right because it was thought that this would allow faster left hand turns, the floats were weighted unequally so as to help counteract the extensive torque from the 800 hp engine, and the AS.2 engine was refined to be as narrow as possible so as to reduce profile drag to an absolute minimum. Seen from the front, the plane looked almost emaciated, yet this added up to the potential for the maximum speed advantage.

The extraordinary lines of the Macchi M.39 concealed a terrible reality — the plane was designed, built and tested in just a few short months and had not undergone sufficient testing to prove its capabilities at any speed, let alone at the highest speeds. Macchi built three racers and two training planes, the latter with lesser horsepower engines. The three planes were constructed and delivered to Lake Varese for a short period of pre-race testing. The Italian Air Service assigned Vittorio Centurione, Mario de Bernardi, Adriano Bacula and Arturo Ferrarini to fly for the Italian racing team. Drawn from the international colors of motor racing, the planes were painted in the Italian Rosso Corsa, which loosely translates to “racing red”.

During the short testing period, just a month prior to the race, disaster struck. The team captain, Vittorio Centurione, perished when his M.39 trainer plane, which was nearly identical but with a 600 hp engine, crashed into Lake Varese. Despite the very limited testing having been accomplished and several known problems with the airplane and engine, the Italians pressed on with a few more tests before loading the planes onto a ship to sail to Hampton Roads or the race. The races, originally scheduled for earlier, were delayed to November to allow the Italian team to make a showing.

While it might sound extraordinary that the Italians should go with equipment that was so unproven, in fact, every nation was in a head-long drive to prove new technologies, design new aircraft and advance their interests for the race, even if it meant taking extraordinary risks. Yet while Italy wasn’t alone in this, it was probably the farthest out on the bleeding edge. If the Americans were to win, the Schneider Cup would be forever lost and that, the Italians had decided, was unthinkable.

On the American side too, the press to advance the maximum speeds created problems. Disaster struck — not once, but twice, though in one case, Lieut. F. H. Conant was killed while flying a a support plane from Washington to Norfolk, rather than one of the racers.

The 1926 Race at Hampton Roads

On November 12 and 13, 1926, the Schneider Cup trophy race was held at Hampton Roads, Virginia. The three Macchi racers were assigned pilots as follows: MM.74 would be flown by Lieut. Adriano Bacula; MM.75 by Capt. Arturo Ferrarini; and MM.76 by Major Mario de Bernardi. Arrayed against the Italians were the Curtiss R3C-2, Curtiss-Packard R3C-3 and Curtiss R3C-4 racers from the United States, all updated and re-engined models of the 1925 winning planes. The English racing team could not complete their new seaplane designs in time for the race and thus did not participate. As with previous Schneider Cup races, the actual races were not head-to-head but rather time trials; planes were released on five minute increments so that they could fly the pylons without interference in a true speed test. At Hampton Roads, the course involved a 50 km lap length and consisted of seven laps for a total distance of 350 km — races were timed on each lap but had to complete a complete, consecutive seven lap race over which the times would be averaged.

Four days prior to the races, on November 8 while in practice runs, the Americans had set a high bar for the Italian team to beat, racing around the pylons at 256 mph. It was an ominous, new world record. Among the Italian team, nobody knew if that record could be beaten — none had ever achieved that at Lake Varese. On November 12, the first day of the race, a major mishap resulted when the American pilot Lieut. Tomlinson nose-dived his Curtiss-Packard R3C-3 into the bay — his aircraft was the reserve plane for the American team. The other two American pilots, Lieut. Cuddihy on Curtiss R3C-4 biplane, which had a 700 h.p. Curtiss V-1550, and Lieut. C. F. Schilt, USMC, on Curtiss R3C-2 biplane, which had a 600 h.p. Curtiss V-1400, both performed well.

On November 13, the race culminated with the high speed runs with both teams going full out, doing whatever it took to try to win. Lieut. Bacula managed a complete run of seven laps but averaged just 218 mph. The American, Lieut. Tomlinson, flying one of the other aircraft, could not get his engine to perform properly and managed an extraordinarily slow average speed of 137 mph. The second American, Lieut. Cuddihy, put in excellent times and at the end of his sixth lap was averaging 239 mph — yet he was forced out with a malfunction before completing the last lap. When Capt. Ferrarini of the Italian team attempted the course, he suffered a burst pipe during the fourth lap, forcing him down to a safe landing. His time over the three laps had been 238 mph, very close to the best American time. Yet the Lieut. Schilt, USMC, had put in an extraordinary run, finishing the full seven laps and putting a speed to beat on the board of 231 mph.

The race came down to Major de Bernardi in the M.39 numbered MM.76. Without concern for the engine or aircraft, once airborne off the water, he simply pushed the throttle to the stop and hoped that the engine would survive the run. He flew the plane smoothly and flawlessly around the course, finishing all seven laps with perfection before landing and taxiing back to the ramp where the M.39 was pulled from the water as de Bernardi stoop up in the cockpit. The officials put his average speed at 246 mph. Though slower than the pre-race record set by the Americans on November 8, it was the winning time for the race itself. The earlier world record time did not count for the Cup win because it was not accomplished during the race itself. That evening, the trophy was awarded to the Italians during a formal dinner celebrating the race finish.

For Major de Bernardi, however, not going home with the record speed was a hollow victory — he knew that the American planes had performed better. The pride of Italy was still at stake and he would settle for nothing but a complete and absolute victory that demonstrated Italy’s ability in the air. Thus, four days later, when weather conditions were right and after the mechanics had tuned his FIAT AS.2 engine as best they could, Major de Bernardi took the M.39 up for one final speed run. Again pushing the throttle to the stop, he completed the full circuit and set a new world record speed of 258 mph, just 2 mph faster than the best the Americans had managed. It was enough, however, and the Italian team returned to Italy with both the trophy and the world record speed in hand. As for Major Mario de Bernardi, he returned as the hero of all Italy.

Aftermath

In later years, after completing a long racing and aerobatic career, Mario de Bernardi flew as a Caproni test pilot. His greatest achievement in that role was undertaking the first tests of the Caproni N.1, Italy’s first jet powered aircraft. In later years, after World War II, he was a regular sight at races and international air meets.

Sadly, on April 8, 1959 — today in aviation history — while attending an air meet at Rome, he took his light plane up to put on an aerobatic show. Part way through the flight, he suffered a massive heart attack. Somehow, despite the pain and his rapidly deteriorating condition, he managed a safe landing. He died shortly after being pulled from the cockpit. It was a sad end for one of Italy’s greatest pilots, but also fitting in its own way, dying while doing what he loved most, flying one last time for the crowds.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The Schneider Cup races after 1926 were no longer an annual meet but rather were extended to every second year. Why?

I noticed that My dad’s godfather, C. Frank Schilt is mentioned in your article. do you have a writer that would be willing to collaborate with me on an article about Frank and rewrite some Marine Corps history? It is quite aviation related.

An interesting question is, “Why in the world did they fly floatplanes with all that float drag if they were trying for speed?” The answer is quite fascinating and a hint can be found by looking closely at almost any of the pictures.

Don, thanks for the response. I was just wondering why the focus was on floatplanes. Can you give us the reason? Thanks.