Published on June 13, 2013

By Thomas C. Van Hare

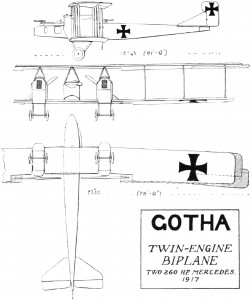

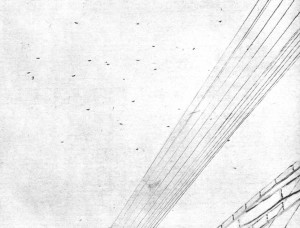

During daylight hours on June 13, 1917, at the height of the Great War and 96 years ago today in aviation history, the German air service made a daring raid on London with just 14 Gotha IV bombers. Despite the best efforts of British defenses, the raiders flew with near impunity and dropped their bombs in what would prove to be the most successful attack on the English capital in the entire war. In all, 162 people were killed and another 432 were wounded, many gravely. While the British initially reacted with disdain, that view would hold only for a few weeks as many pinned the hope of future security on the failure of the bombers to hit any significant military targets. That assumption, however, was wrong — perhaps the Germans weren’t aiming for military targets after all. The era of strategic bombing had begun.

It would take a month more for the British public to come to grips with the Gotha raid and what it meant. Predictably, at first the public compared the raid with the night attacks by Germany’s Zeppelins, a campaign that had ebbed and waned and finally, with effective night defenses, had been beaten back. It took some time for the realization that the bombing of cities and civilians was no longer the unavoidable result of night Zeppelin attacks, but rather than planned goal of a new type of aerial warfare. In the meantime, however, the British clapped themselves on the back, hopeful that the losses the enemy suffered would prove to be too great for them to continue.

Against the backdrop of the mass slaughter on the Western Front, however, such views were absurd. A dozen men lost, a few airplanes downed — how did that measure against the hundreds of thousands lost in the trenches of France?

Hopeful Statements Camouflage Reality

While the full extent of the casualties was not yet fully appreciated, the British public was more uneasy than the press, the government or the aviation community. They knew just what had happened — the attack was markedly different from the damage inflicted by the Zeppelin’s of the previous year. Those huge machines had come at night, dropped bombs erratically and sporadically from high altitude before heading south across the Channel to safety. The Gotha bombers came instead during the day and flew at just 12,500 feet of altitude, dropping their bombs carefully. London’s air defenses had proved inferior to the task, yet still the editors at Flight intoned hopefully in their June 14, 1917, issue:

“We have a shrewd suspicion that the enemy does not regard his attempt on the Thames Estuary last week as an unqualified success. True, the sixteen or so aeroplanes that succeeded in getting over south-eastern England did manage to do some minor damage and caused some regrettable loss of life, but when we remember that toll was taken of them to the number of ten machines, we are entitled to claim that the honours rest with the defence…… The experience he underwent in this last raid is certainly calculated to damp his ardour, and a few more such forays ought to drive home the realisation that the game is not really worth the candle.”

The results were far from what was claimed, however. In fact, the first raids by the huge German Gotha bombers had inflicted the greatest civilian casualties in the entire campaign against London and losses were minimal. More such raids would come as the Germans worked out the details of how to best execute the mission. The hope that the Germans would soon lose interest in such attacks was echoed widely, as repeated in Flight:

“In the case under discussion the effect was not worth it, and by the time the enemy has made half-a-dozen more such raids and has discovered that he has to pay without effecting anything worth while, he will abandon aeroplane raids as he has dropped invasion by Zeppelin. It is very satisfactory to know that our defences have been brought to such a state of perfection as is disclosed by the results to the enemy, and we can rest assured that subsequent raids will meet with no better fate than that of last week.”

A Dose of Reality

With a few weeks, the hard truth dawned on the public when a second attack was launched, again in the daytime. The results of that were addressed in the July 17 issue of Flight, this time with greater balance and in a tone that reflected the rising concern:

“Again London has been subjected to an attack from the air in broad daylight, and the pity of it is that the enemy was again able to inflict a considerable amount of damage to life and property and to get away practically unscathed. Four machines down out of a minimum number of raiders of twenty-two is not flattering either to our amour propre as a nation or to the efficiency of our defences against this kind of attack.”

Another author in the Daily Mail, Mr. de Halsalle, was even more harsh in his assessment in a July 5 article that was entitled, “More Aeroplanes” and carried a dark foreboding:

“…the last aeroplane raid on London was highly successful, considering the number of planes employed. […] If, say, 15 aeroplanes can do such and such an amount of damage to British life and property, what can a raid by 50, 100 or 1,000 accomplish?”

Final Thoughts

The era of strategic bombing had finally begun, threatening the cities and civilians of nations at war. In Germany too, that recognition was complete. News from the Western Front was eclipsed by the discussions of the raid on London. Publicly, the Cologne Gazette offered, “Let us send 1,000 aeroplanes over London, let us set England ablaze from end to end.”

Ultimately, such mass scale air attacks were still impossible in the context of the Great War of 1914 to 1918. The 1,000 bomber raid, however, would come with the heavy strategic bombing campaigns of 1943 and 1944 waged by the Allies against the Germans during World War II. In the decades since, the immense destructive power of air power has been shown again and again to be the deadly key to victory. The final legacy of the Gotha bomber would cast a long shadow indeed.

Thank you for telling this little known story from the Great War on the “Gotha” , probably the most advanced heavy bomber flying aircraft of its day and a big shock to the British aviators of the day and kept under wraps by the War Ministry.

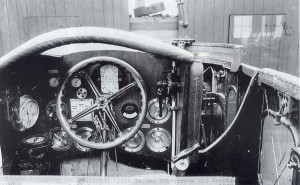

The close up photographs of the machine are amazing

J.C.v B