Published on April 18, 2021

By Thomas Van Hare

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds,—and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air. . . .Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark nor ever eagle flew—

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

That poem is by John Gillespie Magee, Jr. He was both a pilot – and a poet. His poem, “High Flight”, is perhaps the most well-known and best loved verse in aviation history. The story of how Magee came to write his famous poem and what happened to him afterward are not well known, however.

When the Second World War broke out, the United States was a neutral county. It would be more than two years before Japan attacked at Pearl Harbor and America joined the fight. And like many men of his generation, Magee could not stand aside and watch as country after country fell to the Nazis. Therefore, he crossed the border into Canada and enlisted into the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was accepted into flight training in 1940 and a year later he had earned his wings. He was shipped off to England in July 1941.

WATCH THE VIDEO!

Unlike most Americans though, for Magee, England wasn’t some distant, unknown place. His mother was English and he had done most of his schooling there. His father was an Anglican priest from America. The two had met in China as missionaries and gotten married there. He was born in Shanghai in 1922. And when he finished his high school, he was accepted on a scholarship to Yale University, but he chose to fight instead.

He had just turned 19 years old when he shipped off to England in July 1941. On arrival, he was posted then to No. 53 OTU, flying from an airfield in Wales. The term “OTU” stands for “Operational Training Unit”. It’s a type of squadron where new pilots were sent learn to fly high performance fighter planes.

Magee was put into the cockpit of a Supermarine Spitfire Mk I, and he had his first flight on August 7, 1941. Less than two weeks later, on his seventh flight, he took the Spitfire up to high altitude to get a feel for how the plane handled in thin air so far up. He coaxed it around and did wingovers, loops, and rolls — and as he flew along, he recalled the words of poet that he had once studied in school, a man named Cuthbert Hicks. In the poem, “The Blind Man Flies”, Hicks ended it with these words:

Now joy is mine through my long night,

I do not feel the rod,

For I have danced the streets of heaven,

And touched the face of God.

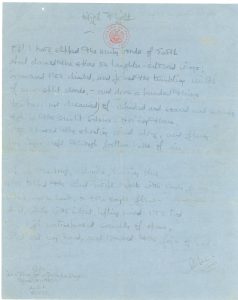

After he landed, taking inspiration from Hicks, he reworked the last line of the poem into his own. Two weeks later he sent it to his parents on the back of a letter, writing: “I am enclosing a verse I wrote the other day. It started at 30,000 feet, and was finished soon after I landed.”

The original poem, as sent to Magee’s father in Washington, DC. Credit: Library of Congress

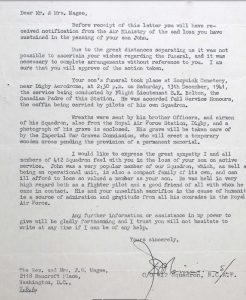

His father was serving at Saint John’s Episcopal Church in Washington, DC, located straight across from the White House and often called the President’s church. Being proud of his son, he had the poem printed in the church bulletins.

Twenty days later, on September 23rd, about the time the poem was first read by the congregation, Magee was ready for combat. He was assigned to No. 412 Fighter Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force, and they flew from the airfield at RAF Digby. The squadron upgraded to the newest model of the Spitfire, the Mk Vb, and he began flying air defense and shipping convoy escort missions right from the start.

On November 8, he flew as part of a twelve plane mission escorting a Bomber Command raid on the railway workshops in Lille, France. When his flight of four Spitfires, crossed the French coast just east of Dunkirk, they were attacked by a squadron of Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A-1 fighter planes, lead by one of Germany’s leading aces, Joachim Müncheberg. In the span of less than two minutes, the other three planes in Magee’s flight were shot down, including his squadron commander. He barely escaped alive. Though he fired his guns, he claimed no damage done.

Luftwaffe ace, Joachim Münchberg. Credit: Polish Archives, Warsaw

A month later, on December 7th, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The next day, the United States declared war and immediately, Hitler declared war on America. With two and a half months of combat operations behind him, he continued to fly for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Sadly, on December 11, Magee was killed – not in action, but in an accident. His flight of four Spitfires had just completed a routine training flight above the clouds. They were practicing air combat maneuvering near the airfield at RAF Tangmere. When the flight turned to return to their base at RAF Wellingore, they spotted a gap in the cloud and descended.

At only 1,400 over the ground, they crossed paths with a student pilot, flying in an Oxford Trainer. The student, Ernest Aubrey Griffin, was just under the clouds and they were on a collision course. It happened so fast that neither pilot had time to react. The two planes collided over Bloxholm, a small village located near RAF Cranwell and RAF Digby, in Lincolnshire. The time was 11:30 am.

Griffin was probably killed instantly. As for Magee, his Spitfire plunged out of control toward the ground. He managed to bail out, but he was too low for his parachute to open. He was killed on impact.

He had been in England for six months and in combat for just two.

The Spitfire Vb that he was flying that day bore the fuselage code of VZ-H. It was the same plane he had flown in on the day he had returned from Dunkirk as the lone survivor of his flight.

Not long after Magee’s death, his poem was featured in newspapers across the United States. The Library of Congress hailed his poem as the being the work of the first poet of the war.

Pilot Officer John Gillespie Magee’s body was laid to rest in the village of Scopwick, not far from where he fell. His gravestone was inscribed with the first and last lines of his poem:

‘Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.’

Magee’s poem reminds us not only of the joy and beauty of flight, but also of the true cost of war. His poem also reminds us of one of the Psalms of David:

“Oh, that I had wings like a dove, for then would I fly away, and be at rest.”

I am reminded of my own experience after earning my wings. Though it was over 50 years ago, the thrill of that solo flight (a “freebee” given to pilots after earning their wings) remains with me. Climbing up the side of a cloud to see beyond. And I tell anyone who is interested “It’s always sunny at altitude”.

High Flight is probably the most beautiful poem I have ever read and if you have ever flown at high altitude as I have, the words capture the amazing sense of limitless space and incredible freedom that you feel. The final words are so beautiful they bring a lump to my throat.

Beautiful tribute and story. As a child, I watched as his poem, “High Flight”, was read by a narrator while the screen showed a plane soaring in the clouds — it was unforgettable. This happened for a time every night in the 1950s as the closing-out message of one of the television stations at 11 pm.

So beautiful brought tears to my eyes

I memorized the poem in high school. I graduated in 1966. It touches the soul.

Touching