Published on June 11, 2012

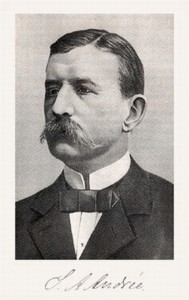

The cold of White Island, in the Arctic north, is unrelenting. Known as Kvitøya, Arctic Norway, the site is desolate and uninhabited. It is also the place where in 1930 the remains of a balloon expedition and the bodies of three men were discovered frozen in the permafrost. After an investigation, it was determined that these were three Swedish Arctic explorers, Salomon August Andrée of Gränna, Småland, who lead the expedition, and two others, Swedish engineer Knut Frænkel and photographer Nils Strindberg (second cousin to famed playwright August Strindberg). Their expedition had taken place in the year 1897.

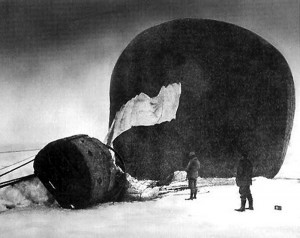

The three men had attempted the nearly impossible task of flying an Arctic expedition to the North Pole by a free hydrogen balloon. In other words, the ballooon would sail on the winds and weather and the explorers would attempt to manage their flight by hunting winds at different altitudes. Departing from Spitzbergen, the explorers made it three days into the expedition before they crashed onto the pack ice in bad weather. Well stocked with provisions, they attempted to work their way out on foot. They were never heard from again.

When the explorers were overdue, a massive rescue operation was mounted to locate them. Many other leading explorers trekked and flew northward over the ice pack. Yet nothing was found — the men had simply disappeared into the harsh and unforgiving Arctic ice pack.

An Incredible Find

Finally, 33 years later in 1930, their final camp site and bodies were found. Among the supplies that surrounded the bodies was one surprising find, a camera and its still undeveloped film, frozen in time by the Arctic weather. The plates were brought to Sweden for evaluation and the photo lab developers went to work to see if any images could be retrieved. Incredibly, they discovered that many of the photos could be simply developed using normal processes — the Arctic cold had preserved the chemical emulsions, if sometimes imperfectly. What the photographs revealed was the complete story of their crash and the months afterward as the explorers struggled for survival on the pack ice of the Arctic. Papers and other gear were also recovered from the frozen campsite. Among these items were a journal that cataloged their complete journey and plans, day by day. This defined almost every aspect of the ordeal that the three men had endured before finally perishing — but the one piece of data missing was just why they had died.

Their campsite still had supplies. Food was available, they could have conceivably lived for many more months, yet clearly, they were weakened. Something had happened that forced the three men to stop on the island and, a short while later, to finally succumb.

The Story Unfolds — Details of a Failed Expedition

S. A. Andrée, as he was called, was an engineer and pioneering aeronautic explorer who sought to reach the geographic north pole by flight. He was an innovator at heart, a true explorer in the classical age of exploration. His job with the Swedish patent office involved reviewing the patent applications of others. Thus, he was well versed in aviation and balloons and he was an expert in exploration.

For his Arctic flight, S. A. Andrée was well connected. He secured funding from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. He was further sponsored by the Swedish King Oscar II and also by no less than Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite (and the same man who would later inaugurate and endow the Nobel Prize).

The three explorers’ first attempt at finding the geographic north pole took place in 1896. Throughout the short summer launch window when weather was mild, somehow the winds did not cooperate. They experienced countering winds almost daily. Ultimately, this forced them to cancel the expedition entirely for the 1896 year, without even making an attempt.

The following year, in 1897, they returned to Spitzbergen to try again. As always, the short Arctic summer exploring season was in July. The team brought their balloon to the launch point and hoped for favorable winds. Almost from the start, however, it seemed that their expedition went awry. That it would end in tragedy was something that the three men could foresee but hoped to avoid.

Launch of the Örnen

On July 11, 1897, winds and weather at Spitzbergen were finally favorable. The three men gathered their supplies and equipment, loaded the hydrogen balloon Örnen (The Eagle) and readied for launch. At lift-off, however, the craft somehow suffered damage when two of its three “sliding ropes” were lost in the first minutes of the flight. These ropes were intended to be dragged on the ice pack’s surface, managing altitude due to their weight (with varying atmospheric and balloon internal pressures, more or less of the rope would slide on the ice below, thus managing their altitude). The ropes also helped to steer the craft in the wind. Even with the loss of the two ropes, the explorers persevered, hoping to make due with just the one remaining.

Yet once again, their luck turned foul. Within 10 hours of starting the flight, they ran into serious weather. Storms and heavy winds combined with freezing rain. The balloon’s flight was erratic and the three men struggled to maintain control. Finally, after hours of battering, their balloon was brought down by ice accumulation from freezing rain. In the 65 hours of flight that they had managed, they had covered 295 miles. It was a long way from their destination of the north pole, but yet still far enough away from land and help. From the moment the balloon crashed, the three recognized that their survival was in grave doubt.

A Failed Attempt to Trek to Safety

Facing few options, the three explorers loaded their sledges with what supplies they had on board the balloon. It would be enough for some weeks and they knew that they could shoot and eat polar bears along the way. This would supplement their diet. Arduously, they began pulling their sledges along the way across the ice packs westward toward one of the survival caches that had been placed by ship in the event of difficulty.

Yet they were trekking not on land, but on the ice pack of the Arctic. The ice pack itself moved on the northern ocean currents. Thus, despite their attempt to walk eastward, the ice pack instead carried them in the opposite direction. They realized this after some days of travel and elected to turn around and work with the ice pack’s movement to a different cache site.

Now navigating their way east and southward, they were able to shoot and eat polar bear to supplement their diet as planned. The going was slow, in fact far slower than they had expected. Repeatedly, their supply sledges had to be pulled up over ice ridges and across gaps and crevices, slowing their progress. Weakened from the difficulty of the journey and with the autumn weather closing in, they knew they would have to bed down for the long winter and wait until spring.

To survive, they constructed an extensive shelter complex — drawings were included in their journal, demonstrating a well-conceived plan. It was an excellent plan and layout with separate rooms for supplies and sleeping quarters, constructed of ice and snow. However, once again, their luck would turn foul. Once the shelter was built, the ice pack beneath the shelter broke up, destroying the shelter and forcing them to press on in search of land, having wasted energy and time in preparing what they had hoped would be their home for the dark months to come.

With few options to find land, they mapped a trek in the direction of the nearest island amidst the ice pack — White Island, known as Kvitøya. Yet once again, ill luck plagued them. One of the polar bears they shot and ate was infected with trichinosis. Afflicted with the disease themselves, they were soon suffering diarrhea. The disease greatly weakened the three men, yet they still made it to White Island — their first land. Yet the trek and disease had taken a huge toll on the three men. Too weak to unload the supplies, they left the sledges at the edge of the ice pack, hoping to recover enough health to retrieve the rest in the coming days or weeks. They pitched just a tent on the land, hoping to build a more extensive shelter once they had rested and started to recover. The tent would clearly be insufficient to survive the harsh winter to come.

The weather closed in hard. Growing weaker by the day, their journal entries grew spotty. The men recognized that they would not likely survive their ordeal much longer. Within a week of arriving on White Island, the first of the three died. They carefully buried his body in a nearby shallow grave and returned to their tent to rest. A few weeks later, the two remaining men were too weak to continue writing entries in their journal. Sometime thereafter, they too died, most likely from complications of the disease trichinosis.

Discovery of the Bodies

In the summer of 1930, the Norwegian Bratvaag Expedition came upon White Island. There, they discovered the frozen tent that still contained two frozen bodies. They recovered what they could and headed southward with news of their discovery. Interest in the story was high and therefore, a month later, the ship M/K Isbjørn (ironically, the name translates from Norwegian as “The Polar Bear”) was hired by a newspaper to sail to the island and do a search to see what else could be found at the campsite. Once on White Island, the newsmen found the third body that had been buried earlier, still in its shallow grave. They also recovered the expedition’s notebooks, journals, and many other objects. Nearby they found a polar bear carcass, partly eaten. It was stricken with trichinosis (whether this was the bear that had infected them or another earlier one is unknown).

On the return of the three explorers’ bodies to Sweden, they were welcomed with great ceremony and celebrated as heroes. The new Swedish King Gustaf V personally attended their burial and gave them men the highest honors. The three were cremated and their ashes interred at the Norra begravningsplatsen in Stockholm. With the cremation of the bodies, however, any hope of definitively proving a cause of death was inadvertently lost. As well, the objects from their failed expedition were placed in museums for public viewing, including the many photographs that documented their terrible ordeal.

The story of the Örnen illustrates the challenges of exploration. Even today, undertaking a journey to the north pole is no simple matter — in 1897, it was a monumental task. The three men knew that the risks were high, yet they persevered in their quest to journey to the north pole. Their attempt, and ultimate sacrifice, is testimony to the bravery of all early explorers to discover and uncover the world in which we live.