Published July 27, 2012

A Miraculous Water Landing

The Chinese aircraft were attacking the Cathay Pacific airliner relentlessly even as Captain Phil Blown pulled the airliner left and right. In the passenger cabin, smoke filled the air and huge tears and holes peppered the fuselage. Both wings were aflame and he could only keep the airliner flying straight by shutting down one of his last two engines. His four engine airliner was now little more than a single engine flaming coffin. Few thought that there was any chance of survival, yet Captain Blown had a plan. If he could just get to the water, he could ditch the plane into the heavy, 10 foot seas. Some, if not most, could well survive. Desperately, Captain Blown dropped from 9,000 feet to sea level in less than two minutes.

At 1,000 feet, the two Chinese fighters broke off their attack, expecting to watch the airliner crash into the sea. Their target, the Cathay Pacific airliner, had both wings aflame, was trailing smoke, and appeared to be in a terminal dive. Somehow, it pulled out hit the first wave, skipping off the wave top over the trough and into a second wave, skipping again — somehow, Captain Blown was managing a miracle landing in heavy, 10 foot seas with only one engine still turning and half his flight controls shot away. In 2009, 55 years after the events of that day, Valerie Parish, at the time a six year old passenger on the doomed plane, later recounted the incredible landing of the plane she had nicknamed “Silver Wings”:

“Silver Wings came to the water at about 260 knots and it was hard for Captain Blown to wash out-reduce that speed. He had no flaps, the plane barely under control. Skillfully, he turned all the engines off, what was left of them, except the #3 engine. He gunned the #3 engine which lifted the nose enough to allow the plane to bounce and lift three times, skimming across the rough water. He landed his burning, shot up plane. The starboard wing caught the water, ripped off, then a huge wave formed and the nose hit at about 160 mph somewhere near the top of it. The tail section broke off and the plane ripped apart, water pouring in.”

Less than a minute later, the plane had sunk beneath the waves. Only ten of the passengers and crew escaped the wreckage. They were floating in the sea. Separated from one another, each wondered if they were the sole survivor. Among the dead would be Valerie’s father, Leonard Parish and her two young brothers, Phillip and Lawrence, ages 2 and 4. Little Valerie would find another passenger, Peggy Thorburn, and ask why they couldn’t get back into the plane and fly home.

Aftermath and Rescue

The force the impact with the water had rammed Captain Blown and copilot Carlton into the instrument panel with such force that their safety harnesses ripped apart. The radio operator, Steven Wong, and two flight attendants, Chief Purser Iris Stobart and Rose Chen, were killed on impact. Injured but free of their seats, the two pilots crawled out of a shattered cockpit side window. Once out of the plane in rough seas, they somehow located and gathered the surviving passengers together. None were wearing life vests. Copilot Carlton found a life raft, but the pilots were wary of inflating it as the two Chinese planes were orbiting overhead.

The two fighters made a low pass at perhaps 750 feet, perhaps checking for survivors, before departing back to their base on Hainan Island. The passengers were sure that had they been sighted, the Chinese would have strafed them in the water. Even after the two planes had gone, they waited for a time before inflating the raft. The two pilots helped load the survivors on board and then scrambled on as well.

Shortly afterward, a French Privateer aircraft arrived from Tourane (Danang), Vietnam. When it began to orbit overhead, the survivors felt that the Chinese would stay away. Steven Wong’s radio call to Hong Kong resulted also in the launch of a Short Sunderland flying boat, a York and a Cathay PBY to attempt a rescue. When the planes arrived, however, it was apparent that the seas were simply too rough to make a water landing. The French Privateer aircraft continued to orbit, hoping that maybe conditions might improve. The other planes started flying search patterns in hopes of locating other survivors.

Captain Woodyard to the Rescue

A few hours later, also in response to the distress call, two Grumman SA-16 Albatross of the USAF’s 31st Air Rescue Squadron arrived. The planes had flown a long way, coming from Clark AFB in the Philippines. On the lead plane, Captain Jack Woodyard, USAF, orbited to assess the situation. Where others were unwilling to attempt the rescue in the heavy seas, Woodyard felt that he had to make the attempt. The seas were more than challenging — in fact, he knew there would be no doubt of a crash if he attempted to land in the heavy seas. Furthermore, the ten passengers on the raft would put his aircraft severely overweight if he were to try to take off again after the rescue. Undaunted, Captain Woodyard started to formulate a plan.

Looking up from the raft, Captain Blown recognized the USAF SA-16 Albatross. He knew that the Americans would try a landing even while the others held off. He also knew that some of his passengers were in dire need of medical attention, some with serious shrapnel wounds. With renewed hope, he yelled out, “The Yanks are coming! The Yanks are coming!”

<= Back to Part 1 — Go to Part 3 =>

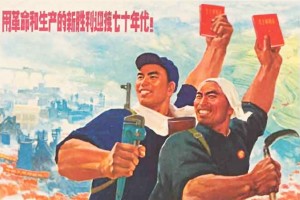

One More Bit of Aviation History

By 1952, the Chinese PLA Air Force (PLAAF) was already equipping with Soviet-built MiG-15 jet fighters and the Lavochkin LA-7s would be reitred. The MiG-15 would prove to be a mystery plane and a serious competitor for the F-86 Sabres of the USAF. It wouldn’t be until 1954 that a defecting pilot (from North Korea) would bring a MiG-15 into US hands at Kimpo AFB, Soeul, Korea. The plane would be quickly whisked out of South Korea and taken to Okinawa for flight testing and analysis. Among others, the famous test pilot Chuck Yeager (first to break the sound barrier seven years earlier) would test the plane.