Published July 25, 2012

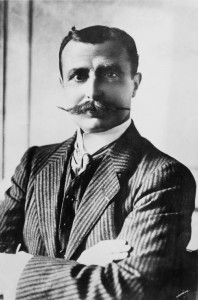

On this date in aviation history in 1909, spurred on by a £1,000 prize offered by a British newspaper called the Daily Mail, the bankrupt Frenchman Louis Blériot flew the English Channel in an aircraft of his own design, the Blériot XI. For Louis Blériot, it would be a flight not only for the prize money, but also to establish his aircraft designs at the forefront of the new aviation industry. It was desperation too — after nearly a decade of pioneering work perfecting his machines, the work had cost his own and his wife’s combined fortunes, leaving them penniless. Indeed, he only had sufficient funds to design and build the plane because, by pure chance, his wife had rescued a boy from falling off a Paris apartment balcony. In appreciation, the boy’s father funded Blériot’s plane — it would be his last hope.

Success was not guaranteed, however, and he set a series of test flights. While preparing in his Blériot XI, he set a new European endurance record of 36 minutes 55 seconds in the air and won a cross-country prize for the distance flown. Based on his calculations of these flights, he knew that he could successfully cross the English Channel — if his little Anzani 25 hp engine held out. This was no mean feat, as engines of the time were far from reliable. Endurance and distance records were not set based on the airframes and aerodynamics, but usually on how long the engine would run before it failed or started running rough. To save weight, he could not even bring a life raft on board the plane. A landing in the English Channel could well prove fatal.

When he was ready, Louis Blériot set out to Les Barraques, France, his planned departure point. The July weather should have been ideal for the flight, but instead it was gusty, causing a several days of delays. Finally, on July 25, 1909, the weather seemed to favor the crossing. After a short pre-dawn test flight, he awaited the official declaration of sunrise (in accordance with the rules of the Daily Mail prize) and, just after dawn, at 4:41 am in the morning, he departed into light winds.

A crowd of well-wishers waved him off to a safe journey. Lacking even a compass, he pointed his plane at the French Navy Rochefortais class destroyer called the Escopette, which was sailing ahead toward Dover, England. On board the French Navy ship was his wife, Alice, as the French Navy had offered to transport her across to meet him in England. His plane soon overflew the ship, however, and Blériot was on his own. Dangerously, visibility deteriorated. He entered a low hanging mist. Flying at 250 feet of altitude, he could see nothing of the world around him at all, just his airplane and its engine gauges. He flew on, trusting the stability of his airplane (this was a time before instruments were invented for instrument flying).

“For more than 10 minutes I was alone, isolated, lost in the midst of the immense sea, and I did not see anything on the horizon or a single ship,” Blériot would later say.

Finally breaking out of the mist, he was greeted with the distant sight of a grey strip of land — but it wasn’t ahead, it was to his left. A stronger wind closer to the English coast had carried him eastward. He was off course. He turned and flew to the cliffs of Dover and then proceeded westward seeking his landing site. For this, he had entrusted Charles Fontaine, a correspondent from Le Matin, with the duty of selecting a good spot for his airplane. Fontaine had done well and had chosen the sloping Northfall Meadow near Dover Castle. The site was at a low point along the cliffs and Fontaine had thought that perhaps Blériot’s plane wouldn’t have been able clear the higher cliffs elsewhere.

Blériot spotted Fontaine waving a large French flag. As it happened, Blériot’s engine was still running well and he crossed the cliffs with ease. He circled twice in a descent. At 20 meters of altitude, he shut off the engine. The winds were gusting, however, and he misjudged the touch down, hitting hard. The landing gear collapsed and he shattered one of his propeller blades. Otherwise, he was fine.

The flight had taken 36 minutes and 30 seconds, just seconds short of the time of his previous record-setting endurance flight. Besides the Daily Mail prize money, Blériot would also receive the equivalent of £3,000 from the French government for the feat, celebrating one of aviation’s greatest milestones. It was, as one writer would later describe it, a “Glorious Flight”.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Louis Blériot’s great flight would indeed establish his airplane as one of the leading designs of the early 1910s. Within the next six months after his crossing, he had orders for over 100 airplanes, bringing revenues of over 1 million French Francs in 1909. Over the next five years, he would sell a total of over 900 of his aircraft. Just before the war broke out with Germany in 1914, with other investors, Blériot acquired another company, the Société pour les Appareils Deperdussin. As its new president, he renamed the company to the Société Pour L’Aviation et ses Dérivés, or more commonly known by its initials as SPAD. His company would go on to produce the storied SPAD S.VII and the SPAD S.XIII (Rickenbacker’s favored fighter plane), among others. Sadly, Blériot would suffer a heart attack and die on August 1, 1936, at age 64 — truly one of the great pioneers of aviation history.

Thank you. ::