Published on August 27, 2012

The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the following awards in recognition of gallantry displayed in flying operations against the enemy: — Distinguished Flying Cross to Acting Squadron Leader James Herbert Thompson (70671), Reserve of Air Force Officers, No. 269 Squadron and Flying Officer William John Oswald Coleman (42395), No. 269 Squadron.

“Squadron Leader Thompson and Flying Officer Coleman, were pilot and navigator bomb aimer respectively of an aircraft in which they carried out a successful attack on an enemy submarine. In very poor weather conditions, Flying Officer Coleman skilfully navigated to the position and, co-operating splendidly with his pilot, attacked with such good effect that the submarine surfaced. When Squadron Leader Thompson opened fire with his machine guns, the submarine crew waved a white flag. One of his Majesty’s destroyers later took charge of the submarine. The success of the operation was undoubtedly due to the splendid teamwork of these two officers. Both Squadron Leader Thompson and Flying Officer Coleman have previously carried out numerous operational missions.”

So read the citation from the King of England to two men with the Royal Air Force for their action seventy-one years ago today, on August 27, 1941. Given the wartime conditions, a more precise description of the events was carefully omitted from the award. What happened is nothing short of a miracle — it is the one and only time in history that an airplane has captured a submarine at war.

No. 269 Squadron in Iceland

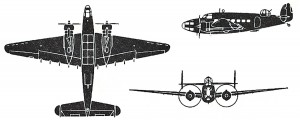

The Royal Air Force’s No. 269 Squadron was a maritime patrol unit that initially flew obsolete twin-engine Avro Ansons out of RAF Wick. The squadron had built considerable experience in maritime operations and had logged nearly a dozen attacks against German U-Boats as well as raids against Norway and multiple attacks on the Germany Navy’s capital ships, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Admiral Hipper. Finally, between March and June 1940, No. 269 was reequipped with the newer, more sophisticated and capable Lockheed Hudson I. On July 10, the squadron redeployed to RAF Kaldadarnes, a newly constructed airbase in Kaldaðarnes, Iceland, just southeast of Reykjavik on the island nation’s southwestern shore. Five days later, it was fully operational with 18 Hudsons on its rolls.

From its new base at RAF Kaldadarnes, No. 269 was to cover the central Atlantic in the ongoing Battle of the Atlantic, in which German U-Boats were targeting American shipping — the lifeline of the Lend-Lease Program to England during the months before America finally entered the war in December of 1941. Critically, the Lockheed Hudsons were equipped with the new ASV Radio (Anti-Surface Vessel), an airborne-mounted surface search radar system. Rather than flying patterns searching for U-Boats on the surface by sight, with the radars, targets could be acquired at range. With a blip on the radar screen guiding them in, the aircraft could set up an attack coming out of the sun and at high speed. The Lockheed Hudson could carry four 250 lb depth bombs and as well were equipped with a machine gun.

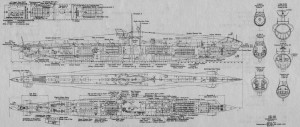

The German Submarine U-570

The U-570 was a newly built Type VIIC boat that had launched from Kiel and had entered into the Kriegsmarine on May 15, 1941. The U-570 was placed under the command of Kapitänleutnant Hans-Joachim Rahmlow, an experienced officer but still new to U-Boats. Most of his crew were green, including the captain’s top two officers — his First Watch Officer had a couple of months experience in U-Boats and his Second Watch Officer was newly commissioned. After a short shakedown and some very limited training in a Baltic cruise the submarine was ordered to base out of Lofjord, north of Trondheim, Norway.

In August, German code breakers of B-Dienst deciphered a British Admiralty message regarding the upcoming schedule for the passage of a large convoy of merchants south of Iceland. With time to prepare, a Wolf Pack of no less than 16 U-Boats was organized to intercept the convoy — among the submarines deployed would be U-570, which quickly departed for the North Atlantic on its first patrol.

The Engagement — Hudson vs. U-Boat

On the morning of August 27, 1941, to patrol in support of the approaching convoy, a No. 269 Squadron Hudson under the command of Acting Squadron Commander James Thompson along with F/O William Coleman picked up a surface target on their ASV Radio at a distance of 14 miles. It was 10:50 am. Although they didn’t know it, the U-570 had just surfaced. The latitude-longitude position was 62° 15′ N x 18° 35′ W. The U-Boat captain was hoping to recharge its batteries in the relative safety afforded by the poor weather conditions and rough seas of the day. Immediately, the Hudson turned toward the target and closed in an attack profile. Ahead, coming out of the mist, they recognized the low profile of a German U-Boat running on the surface. At that moment, the captain of U-Boat, Kptlt. Hans-Joachim Rahmlow, also heard the approaching aircraft. Even if he couldn’t see it, he ordered an emergency dive to escape — the crew were well-skilled at this at least, since this was a basic requirement of submarine operations and they responded perfectly.

Passing overhead the U-570, the Hudson dropped all four of its 250 lb depth bombs in a spaced line. The fuses were set to explode at a depth of 50 feet — a good prediction since the submarine was already mostly underwater as the plane roared overhead on its bombing run. Three of the depth bombs exploded harmlessly nearby but the fourth was very nearly a direct hit — it exploded just 10 meters off of the bow of the U-Boat, crumpling part of the forward structure of the bow and knocked out electrical power inside the boat. In darkness (U-Boats of this type did not have automatic emergency lighting) and facing numerous small water leaks, the inexperienced crew panicked. The engine room crew ran forward reporting poisonous chlorine gas inside the boat from overturned batteries. With this, the watertight door to the engine compartment were sealed to prevent the death of the crew. With no choice, Kptlt. Rahmlow ordered his U-Boat to surface and fight it out against the attacking aircraft.

As soon as the submarine reached the surface, the hatches were flung open and the crew ran to the guns. Amidst the heavy seas rolling the submarine, they quickly realized that they could not effectively defend the boat. The Lockheed Hudson was already coming around for another pass and Rahmlow realized that another attack by depth bombs would be their end. At the time, he didn’t realize that the Hudson had dropped all of its depth bombs and was left with just a single machine gun. On board the Hudson, Acting Squadron Commander Thompson opened fire and began to rake the submarine with gunfire from a diving pass. He was stunned to see the crew suddenly bring up and start waving a white sheet, the universal signal of surrender. He ceased firing and pitched up to pull around in a tight circle to examine the submarine. As he orbited, the U-Boat made no further efforts to defend itself and continued to wave the white sheet. He radioed in a report to the squadron asking for other aircraft and a ship.

Aftermath of the Capture

The U-Boat was laying low in the water, rolling heavily and clearly had sustained some damage. Thompson called for additional aircraft and also for a message to be passed to the Royal Navy to get a surface ship to the area to fully take possession of the vessel. Meanwhile, in the radio room, the German crew went to work destroying their precious ENIGMA coding machine and key code booklets, throwing the shattered pieces overboard into the deep of the Atlantic. Soon, a second RAF aircraft would join the Hudson — a Consolidated Catalina from No. 209 Squadron. Hours would pass before the Royal Navy arrived — the anti-submarine trawler HMT Northern Chief. Amidst some miscommunications, some gunfire (a warning shot that was misfired actually injured some of the U-Boat crew members), everyone was surprised by an errant attack by a Northrop N-3PB of 330 (Norwegian) Squadron (this being a mistake that was soon ordered off).

The U-570 was towed to the shores of Iceland and beached at Þorlákshöfn to prevent its sinking. Repairs were made and the vessel was towed into a better harbor at Hvalfjordur for examination and evaluation. It was later determined that had the U-Boat’s crew been more experienced, they would not have likely abandoned the engine room — indeed, no poisonous chlorine gas was present. As such, the U-Boat would have likely escaped. Ultimately, the U-570 was taken to Scotland and renamed the HMS Graph (a reference to mathematical graph paper since so many tests and graphs were made when determining the capabilities of a Type VII-C U-Boat. The submarine was then used in a number of Royal Navy operations and patrols. Critically, it was also engaged in a very secret program — training special teams to rapidly enter into damaged German U-Boats and know where to go to seize the ENIGMA devices and code books before their crews could destroy them and scuttle the boats. It was daring work.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Anti-Submarine operations of the British and Americans equipped with radar spelled the end of the Battle of the Atlantic. Unable to hide while on patrol, Germany’s U-Boats were hunted down and sunk in large numbers. This allowed the USA to ship enough cargo and men to Europe to set the stage for the invasion of France. The new airborne radar system, or ASV as it was called in those days, was only part of the solution, however. Much of the success of the aerial campaign against Germany’s U-Boats was due to the code breaking efforts at Bletchley Park, in which the German submarine codes of the ENIGMA machine were cracked. Armed with the deployment orders and position reports of German U-Boats, the allied aircraft knew approximately where to fly in the vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean. As for the U-570 ENIGMA, as mentioned it and its code books were destroyed and thrown overboard by the security conscious crew. However, they missed cleaning out the radio room files — in the draws, the allies recovered paired messages, coded and decoded versions of each message received to that point. Armed with those, it was an easy matter for Bletchley Park to decode the messages to other U-Boats for the period of the first two weeks of August.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

How many and which U-Boats did just the 18 Lockheed Hudsons of RAF No. 269 Squadron sink during World War II from their base in Iceland?

As a little boy I was invited to swim in Herbie Thompson’s swimming pool in Welton, East Yorkshire, and met him on a couple of occasions at the poolside in his garden. This would have been about 1976. He was very kind and I enjoyed those summer afternoons very much. I had no idea at the time that he was a wartime hero or had pulled off such a remarkable feat, until my mother mentioned it this evening and I Googled the event, bringing me here. Truly remarkable.

The squadron that captured U570 was actually my father’s squadron. He was Squadron Leader William Chape and he was injured at the time of this event so not flying. I actually visited Herbie “Tommy” Thompson in 1987 with my mother and stayed with Herbie and his wife for 2 nights. It was an absolute pleasure to meet Herbie who knew my father well. At that time his pool was in something of a mess following some storms. I have lived in Perth Western Australia since my parents moved here in 1955. My father passed away in 1979.

I used to work for Mr. Thompson many years ago and remembered the incident above during the war. Is it possible to get a copy to show to my friends.

Were there any other crew on board the Hudson besides Thompson and Coleman? If so, are their names known?

U 570 photographed from one of the circling aircraft as the Anti Submarine Warfare trawler approaches her.

My father Henry Charles Parsons Gourley was based in Iceland during 2nd world war. He was with 269 Squadron his RAF number is 1307603. He is 97 years old now and has Altzheimers. He can still remember his Air Force number but can’t remember things happening now. He is in a wonderful nursing home Annfield Nursing Home in Stirling, Scotland and I write this as his eldest daughter.

My dad tells me he was a Corporal and a Morse code operator and PE instructor. He used to tell us of his time in Iceland. A few years ago I visited Iceland and saw where RAF base was. I would like to kow if anyone knew my dad or has any photos of the base in Iceland during WWII or of his squadron — 269 Squadron.

Even now, he is always smiling, never complains, and still gives me a solute when I ask him his Air Force number.

Please message me at: dorothykelly@me.com

Most interested to read this as W.J.O. Coleman (know in the family as Jack) was my cousin.

Jack was born in Hendon on March 6, 1913, and died on May 8, 1995, in Berkhamstead where he is buried.