Published on September 19, 2012

As the plane taxied out toward the runway, the air traffic controllers on duty looked at amazement at the monstrous addition bolted to the top of the fuselage. Surely, nothing that weird could fly, they reasoned. With a sinking feeling, they realized that the pilot intended to take off. What they were looking at seemed a monstrosity — an ex-Pan Am Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, lengthened at the center point with a 5 meter long extender piece taken off a different B377 (this one ex-BOAC) with a huge, bulbous cargo hold ballooned over the top of the fuselage. When the pilot stopped at the hold short line and requested permission to take off for a first test flight, the tower controller first reached for the phone to scramble the crash trucks and fire engines. With that accomplished, he intoned, “Aero Spacelines, you’re cleared for take off….” As the plane started to roll, all eyes were on it — and not a few bets were placed that it wouldn’t fly.

A Shocking Concept

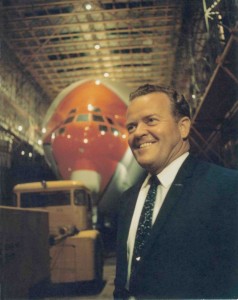

On this date in aviation history, on September 19, 1962, one of the most bizarre aircraft modifications ever accomplished made its first test flight taking off from Van Nuys Airport in California. The plane rolled down the runway into the unknown world beyond the limits of aeronautical engineering theory and into the air. Nobody knew whether the aircraft would actually fly — in fact, many suspected that it couldn’t, including several aeronautical engineers. At the controls was John M. Conroy, a former USAAF B-17 pilot — he had personally funded the effort out of his own pocket. The copilot on this first test flight was Clay Lacy, a former United Airlines pilot and former California ANG C-97 Stratofreighter pilot. The aircraft was built with one primary purpose and customer in mind — NASA.

America’s Moon Problem

With the beginning of the 1960s, Kennedy had declared that America was on the way to the Moon. NASA found it had a problem shipping newly constructed rockets from its west coast contractors to Cape Canaveral in Florida. The original plan, putting them on ocean-going barges through the Panama Canal, proved unworkable. The trip took two to three week and, on arrival, the fragile rocket boosters were dented, dinged and corroded from the salt spray. On hearing of NASA’s quandary, John Conroy had looked across the field at Van Nuys where his friend, aircraft broker Leo Mansdorf, had been storing B377 Stratocruisers that he had acquired, uncertain if they had any resale value. Surely, the big planes could be used, he thought, and it just might solve two problems — NASA’s and Mansdorf’s.

Air shipment seemed reasonable enough. The rocket components were extremely lightweight, though the problem was that they were simply huge. No aircraft had a cargo hold large enough as just one stage of the rocket was 40 feet long and 18 feet in diameter. Conroy started working the problem, literally on the back of a napkin with Mansdorf. Together, they thought that it might be possible to modify a B377 by adding a larger cargo bay atop the fuselage. He prepared a rough design series with some drawings and presented the idea to NASA in person, hoping for funding.

However, the NASA management doubted that it could work. Several professional aeronautical engineers reviewed the concept and declared it unworkable. One NASA official quipped that the contraption looked like a “pregnant guppy”. The trip wasn’t entirely a loss, however, as he found some interested and supportive parties — if he could make it work, they told him, a contract would likely follow…. But of course, no guarantees. One of those who expressed support was the famous Wernher von Braun, who liked Conroy’s swashbuckling, can-do attitude.

Conroy returned to California and mortgaged his house, used his personal savings and borrowed everything he could to build the plane on his own. He even sold his car to fund the project. It still wasn’t enough and he was able to find venture capital funding from William Ballon. Lacking funds to “do it right”, he coined an operating phrase that would carry him through the project, “Built to suit, draw to match, and paint to cover.” In essence, Aero Spacelines cut years off of the development time by just doing it, cobbling the parts together with 2×4 braces, hope and baling wire. What worked they drew into engineering plans after the fact. While risky, Conroy just had to hope that his prototype would fly.

First Flight and NASA’s Response

To test the project, first the team added the ex-BOAC lengthening section and test flew it. It worked fine, though it was a minor modification. Then, they had to do the real work of adding the huge “volumetric” cargo hold atop the fuselage. Conroy had the skin bolted on, leaving the regular fuselage in place for strength and to reduce the number of modifications needed. On September 19, 1962, they logged the first test flight. The plane flew perfectly and when they landed, the tower controllers recalled the crash trucks and fire engines. In honor of the earlier NASA officials off-handed comment, he named the plane the “Pregnant Guppy.” He had to take it to NASA’s offices in Alabama to show them that the concept worked, yet he had no money left. He would have to borrow fuel for the cross country flight. Conroy had over $1 million invested in the project — he was flat broke and had a long line of creditors hounding him.

After filing with the FAA for approval to fly the non-certified plane to Alabama (it was approved, but only for a route that was entirely over countryside from end to end), he borrowed the fuel and made the flight. Once in Alabama, the Pregnant Guppy was greeted with awe. It flew — somehow — and if Conroy could be believed, it was the answer to their dreams. Wernher von Braun, himself a rated pilot, asked to personally check it out as copilot for a test flight. Conroy agreed and made the best in flight sales pitch of his life, even shutting down two of the engines quietly while von Braun was flying. At that point, when von Braun realized that there was no question about the viability of the project. After landing Conroy had two challenges — one, getting a letter of intent; and the other begging NASA for enough fuel to take his plane back to California.

Near Disaster

Returning to California with the promise of a contract Conroy was able to hold his creditors at bay while the team at Aero Spacelines did the work to turn the mock-up into a real cargo carrier. They cut away the “inner” fuselage and rewired the plane and control systems to allow the huge cargo bay to be used. The plane flew perfectly. Soon they had put over 50 hours of test flying. The last remaining challenge was to prove that the plane could carry the heavy loads required.

Thus, in the Spring of 1963 the plane was readied for its heavy lift test flight at Mojave, California. Sandbags and a full fuel load pegged the plane at its projected maximum gross weight. The pilot that day was Jacky Pedesky. As the plane lumbered down the runway, everything was within operating limits. When the pilot pulled back on the control yokes, the plane rotated and slowly rose into the air — too slowly, in fact. It seemed only barely able to climb. Without sufficient runway ahead to land, they had no choice but to press on. The airspeed was pegged at 128 kts — the plane was lumbering along just above the ground. Gingerly, they inched upward into slowly rising terrain ahead. For every foot they climbed, the terrain rose underneath the plane equally.

The coastal plain gave way to the hills and straight ahead was the town of Boron, California. They were still skimming the tops of bushes and hills as they neared the town. As an awkward silence filled the cockpit. Nothing seemed to work, even as the pilots gingerly tried to climb the plane. If they turned, they would fall off their altitude and hit the ground.

Then the flight engineer reported that their number 3 engine was overheating and starting to run rough. What should I do, should I reduce power? Jacky Pedesky replied, don’t touch it, let it burn up if that’s what it is going to do. Somehow, as the plane reached the town, it began to climb. Maybe enough fuel burned off to lighten the load. Bit by bit it clawed upward. Somehow, they passed over the town, barely clearing the trees and buildings. Once beyond, they gained sufficient altitude to turn back for a return to Mojave and made a smooth, safe landing.

Once on the ground, the engineers lightened the aircraft by 8,000 pounds before the next test flight. After a demonstration flight for NASA with a mock-up of the rocket booster on board, the airline signed a contract to fly on revenue runs — Conroy and Aero Spacelines were in business.

Final Notes

At first the Super Guppy supported NASA’s Gemini Program’s Titan II transportation requirements. The plane would position to Baltimore, Maryland, and pick up Titan II rocket stages and fly them to Cape Canaveral. Based on the success of the aircraft and his new contracts with NASA to also support the Apollo Program, John Conroy built a larger version of the aircraft with an even larger cargo hold. This would be based on a YC-97J, which he called the Super Guppy. In the end, he built 25 of the Super Guppy modifications to address the large demand from NASA for heavy lift of high cubic volume equipment and rocket components. Each aircraft was customized to the requirements of NASA’s upcoming space flight needs. The B377 could transport Apollo S/C and components, while the YC97J was specially built to carry S-IVB stages, instrument units, LEM adapters and F-1 engines. After negotiations, Conroy and NASA settled on a price of $16 a mile for flights of the larger Super Guppy.

In the end, John Conroy’s Super Guppy was the key aircraft that got America to the Moon. Wernher von Braun gave Conroy and his company the ultimate compliment when he summed it up succinctly, “The Guppy was the single most important piece of equipment to put a man on the moon in the decade of the 1960s.” Against all odds and based on just his own faith in his idea, his own funds and his hopes, John Conroy had made history.

One More Bit of Aviation History

NASA has a long history of developing specialized transportation devices for its rockets and equipment. While the Super Guppy was big, it was still far short of the size and load bearing capacity needed to transport the Space Shuttle fleet. For that requirement, NASA instead settled on a piggy back design, mounting the Shuttle on a set of pylons above the top of a Boeing 747 that had been modified specifically for that purpose. Meanwhile, Airbus and Boeing borrowed from Conroy’s Pregnant Guppy concept and build their own “volumetric” designs. These specialty aircraft still fly today all over the world.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What cargo aircraft can lift the greatest load (in weight, not cube) in the world today?

The Antonov An-225

By the way, Airbus actually used a fleet of Super Guppies to transport airplane pieces before they developed their Belugas.

I came to this site to get a link to some photos of the Guppy for a friend of mine after telling him my story.

In August 1962 I was a draftsman at Strato Engineering, a Burbank firm subcontracted to AeroSpace and charged with making drawings for the conversion process on the Pregnant Guppy. The owner of Strato was a man named Abraham Moses Kaplan. The head of the drafting group was Eugene “Gene” Stanley, a former pilot in WW2.

I personally made many of those drawings including the bulkhead at the back of the cockpit as well as the installation of airflow ducts for ventilation into the tail section, and many other routine drawings involving the modification — so many I don’t even remember any of them specifically.

I can personally attest to the fact that many times I had to drive to the Van Nuys Airport, climb up the scaffolding surrounding the plane and find a specific location of modification, make drawings on a yellow tablet, take some tiny black and white photos and return to Strato to make the drawings match what was already built. Apparently, Jack Conroy had GREAT confidence that his design would work! Thanks for your great site!

Hi Jim,

Eugene Stanley is my father-in-law. He had a storied aircraft career from his time as a Thunderbolt pilot in WW2 through many commercial and military aviation projects all the way into the 1990s, including his time at Strato.

My wife tells the story about how her dad pulled her out of school one day and took the family to the Van Nuys airport to watch the first Guppy test flight referenced in this article. That was a memorable experience for sure.

My background was flying in Navy P-3 Orions, so Gene and I had plenty of great flying stories to share. Sadly, Gene is no longer with us, but the success of the Guppy project he and so many of you participated in lives on.

Thanks to all of you for your hard work and dedication on the Guppy project and countless others that made this country great.

Kurt

Wow! Gene Stanley’s son-in-law!! I am the “Jim Luff” you responded to “4 years ago”. I happened back to this site when writing my “life story” and wanted to review dates!

Gene was a wonderful guy! He took the drafting crew out one afternoon to teach Golf — the one sport I never played!

And Mr Kaplan ok’d it!! I started my drafting career at Lockheed on P2V and P3V drawings! If you ever want to chat I am at wordcrafter@att.net.

HI Jim,

I have a modification shop that rebuilds Stinson Gullwings and saw your note on this site.

I own some of the old Wardlow STC’s for the conversions to the Stinson SR-10F. Many of the drawings were done by STRATO, E. Stanly and A.M. Kaplan. I’d like to talk to you sometime if you did any work on the Stinson project for Wardlow. Might answer some questions.

Give me a call 570-836-4800. Thanks Charlie

“My favorite thing about the Guppy is that it is unique. There were a few others in the past but this is the last operating Guppy in the world. Everywhere we go there is a crowd waiting for us and I love to talk about the aircraft, its incredible history, and our mission.”

I was raised in Van Nuys, near Balboa Boulevard and a few miles from the Van Nuys Airport. My uncle had a plane there and would take me and my Dad flying a couple of times each month. A friend and I became regulars at the airport. Those were the days when you could ride your bike into the airport and ride around looking at some really cool planes.

One Saturday we went to the airport and stumbled on the biggest airplane we had ever seen. The stairs were down so we parked our bikes and went inside. We got caught but the one who caught us gave us a complete tour and I got to sit in the captains seat — it was the ‘Pregnant Guppie’.

All of us in my family watched later when the plane made its takeoff as George Putnam reported on the historical flight.

I am attempting to find out what happened to Strato Engineering. I am working on a project which started with the stress analysis provided by Strato. Do you have any info on what happened to the company? Did it get bought out? If so by what company? Anything you can provide would be greatly appreciated.

My father, Gene Stanley, worked for Strato for 20 years or so. Eventually, they lost their government contracts and closed their doors in the early 70’s. My father worked on the project you mentioned. I remember him often talking about it. He was involved in several interesting and diverse projects during his time with Strato.

I was in the USAF stationed at DMAFB from 1964 to 1968 and was an aircraft refueler. I serviced N1038V a few times when it stopped over at the base. I was 19 years old the first time I saw it land and takeoff and I thought it was amazing something that big could actually fly!

I was there the day it took its first test flight. I remember distinctly my parents coming and taking me out of school. I was 7 years old. I watched the grown men surrounding me debate whether it would make it off the ground, and how astounded they were when it did. My father, Eugene Lowell Stanley (Gene Stanley) was the main engineer on the project. The only time I’ve seen his named mentioned in relation to the Guppy was in a French publication. I thought I’d give him a shout out.

Hi Holly, My name is Chuck Dahlin; you won’t remember me but I remember you, your dad, mom, Millie, and brother Billy. I have vague memories of your apartment in North Hollywood, maybe Studio City, before your parents bought the house on Corbin. Our dads served together on Ie Shima. They shared a tent. They flew the P-47N (333rd sqdn. 318th fighter group.) They stayed in touch after the war and your dad facilitated my dad’s hiring at Strato in 1952 . Abe Kaplan was a wonderful man and a brilliant engineer. Strato was originally located on Lankershim just north of Camarillo and moved to Empire avenue in Burbank. My dad left Strato in 1962 and worked at Weber AC till he retired. The last time I saw your dad we played a round of golf at balboa in 1980 something. Around 2010 as my dad’s health failed I looked on the web and found Dr.Bill Stanley in Bakersfield. I read further and learned Gene had passed away not long before and decided not to pursue this endeavor. Your dad was well respected.Hope you and your family are doing well.