Published on September 15, 2012

“You’ve got to be able to shoot from any position. From left or right turns, out of a roll, on your back, whenever… a series of unpredictable movements and actions, never the same, always stemming from the situation at hand. Only then can you plunge into the middle of an enemy swarm and blow it up from the inside.”

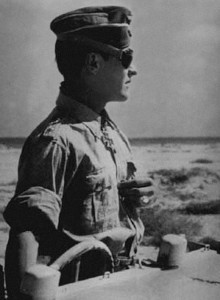

So said Hans-Joachim Marseille regarding his fighting tactics. One of Germany’s top aces from World War II, he was widely regarded by his peers as one of the best, if not the best fighter pilot in the entire Luftwaffe. Today in aviation history marks the 70th anniversary of Marseille’s famous mission on September 15, 1942, which not only marked his 150th kill but also saw him shooting down seven British P-40 fighters in just eleven minutes of combat in the skies over North Africa.

A master of deflection shooting, Marseille was nonetheless barely average when it came to the routine chores of flying. His landings were substandard and many said he was considerably below squadron requirements. On the other hand, he also had the unique ability, once airborne, to push his plane to the limits and fly it with near perfection. He was a rash, handsome and popular young man who had so many girlfriends that early in his career while based in France he often was scrubbed from missions because he was too tired to fly.

A Berliner, he was confident, overbearing, and rarely followed orders well. In today’s air forces, he probably wouldn’t make it out of flight training. Yet he stands as one of the greatest aces of all time. Prone to disobedience, he was “fired” from one squadron and reassigned twice. He was finally “tamed” through careful mentoring of the Gruppenkommandeur of JG 27, Eduard Neumann, who said, “Marseille could only be one of two, either a disciplinary problem or a great fighter pilot.”

The Tactics and Artistry of the Ace

Hans-Joachim Marseille’s score was in large part due to three factors. First, he had the best eyesight in the entire staffel — where others would see nothing, Marseille would pick out enemy aircraft at extraordinary distances. This allowed him to position himself and his formation above and ready to strike with maximum advantage in a lightning attack, taking the British pilots by surprise.

Second, to say that he was deadly at deflection shooting is an understatement — he was, in the words of the other pilots in his staffel, an “artist”. He could shoot from a high-G turn against a turning target and still hit with unerring accuracy. Whereas others would need to line up from behind, Marseille could estimate where his gunfire would hit with extraordinary precision. Sometimes, he required just 15 rounds to bring down each of his opponents. Typically, he hit the engine or cockpit only.

Finally, Marseille developed a method to address the favorite defensive tactic of the British Desert Air Force (DAF) — a formation from World War I known as the Lufbery Circle. When at a disadvantage, the British would take up this type of defensive circle. An enemy pulling in behind one target would find that he was under attack from the next British plane back in the circle. Marseille perfected a different type of attack, as described by a fellow Luftwaffe pilot, Werner Schrör:

“During the fights over the convoys to Tobruk, the British introduced the defensive circle [ed: describing a Lufbery Circle of the World War I era]. It was very efficient, but then Marseille disenchanted it; he would dive down near the circle, pull out and zoom into it from below. He reached the level of the circle just before stalling, just in time to level off, shoot down a Tommy and start to spin to sea level, where he pulled out at the last second (it was impossible to follow him). He then climbed back to his own formation and repeated the performance until the circle broke up. No other German pilot was able to copy Marseille’s tricks, although all made attempts to do so, and sometimes succeeded in breaking up the circle.”

Seven Kills in Eleven Minutes

On September 15, 1942, he encountered a large flight of British P-40 Kittyhawk fighters of the Desert Air Force (DAF). Immediately, the British DAF pilots formed into a Lufbery Circle. As usual, Marseille dove down, pitched up and took his deflection shot. At 17:51, he shot down his first opponent before dropping away in a spin. Then he did it again at 17:53. And again at 17:55. Again at 17:57. Then again at 17:59 and yet again at 18:00. Finally, he shot down the seventh plane 18:02, marking his 151st kill. The remaining British DAF fighters finally scattered and Marseille returned to his base.

Two weeks later, on a routine escort mission covering a flight of Ju 76 Stukas, while flying a newly assigned Me 109G (not his usual plane), he suffered an engine fire. It had been an uneventful mission until that moment. He tried to return to base but was unable to stay with the plane as the cockpit filled with smoke. Finally, he radioed that he had to bail out — his last words described the smoke building in the plane, “I’ve got to get out now. I can’t stand it any more”. He attempted to jump, but his body struck the tail of his Messerschmidt, shattering the left side of his chest. He was either killed instantly or knocked out from the impact. His parachute never opened. His squadron mates had watched his body plummet to earth. Later, his body was recovered from the desert sand and buried at Derna, Egypt. He was just 22 years old.

A Final Controversy

In the past twenty years, historians have questioned Marseille’s combat claims. Some make note that British records show fewer aircraft shot down one some of the days he flew than he actually claimed. While they used this evidence to discount his claims, in at least one case, subsequent further study uncovered that the British squadron had misreported, apparently to cover up the losses. It is impossible to tell what Marseille’s real score was, though this is not a unique issue with his combat record and seems to apply to most aces of that era equally. Commonly, fighter pilot claims can be inadvertently inflated, sometimes by as much as one third. Put simply, sometimes damaged planes dive away and are thought to have been shot down, but before impact, out of sight of the hunters, their pilots pull out of their spinning dive and fly home.

For a pilot who was credited with shooting down more than 150 planes, that might mean that he “wasn’t so great after all” — maybe he only had 100 true kills to his credit (which seems an astonishing claim in and of itself). In the end, the argument seems pointless and does nothing to diminish his extraordinary record and skill. Indeed, only 29 Luftwaffe pilots had higher scores than Marseille, yet all of them built their records in the skies of the Eastern Front, fighting inferior Russian planes and pilots. Hans-Joachim Marseille’s opponents were almost all British and American — they were far from inferior in training or tactics. Rather, Marseille was simply the master of the skies and rightfully earned his nickname as the “Star of Africa”.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Hans-Joachim Marseille’s career as a fighter pilot was short and deadly. He flew his first combat mission during the Battle of Britain, on Wednesday, August 13, 1940. Eleven days later, he claimed his first kill off of Kent — either an RAF Spitfire or Hurricane. In the 25 months that followed, he flew a total of 482 missions, of which 388 were combat missions, and scored 158 total kills in that time. In his final month of combat during September 1942, he scored 54 kills. Given that he was killed in a non-combat event, his grave marker bore the simple declaration: “Undefeated.”

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What was Hans-Joachim’s most deadly day? How many planes was he credited with having shot down over how many sorties that day?

Sept. 1, 1942, 17 in one day. The next day he was notified that he would receive the Diamonds. I wrote the book, The Star of Africa.