Published on September 17, 2012

“On the fourth round, everything seemingly working much better and smoother than any former flight, I started on a larger circuit with less abrupt turns. It was on the very first slow turn that the trouble began…. A hurried glance behind revealed nothing wrong, but I decided to shut off the power and descend as soon as the machine could be faced in a direction where a landing could be made. This decision was hardly reached, in fact I suppose it was not over two or three seconds from the time the first taps were heard, until two big thumps, which gave the machine a terrible shaking, showed that something had broken….

“The machine suddenly turned to the right and I immediately shut off the power. Quick as a flash, the machine turned down in front and started straight for the ground. Our course for 50 feet was within a very few degrees of the perpendicular. Lt. Selfridge up to this time had not uttered a word, though he took a hasty glance behind when the propeller broke and turned once or twice to look into my face, evidently to see what I thought of the situation. But when the machine turned head first for the ground, he exclaimed ‘Oh! Oh!’ in an almost inaudible voice.”

The Crash

Those would be Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge’s last words before the crash, which would take his life. The passage above was written by Orville Wright’s own hand in a letter to his brother Wilbur. Orville Wright himself suffered serious injury, though he recovered from the crash at Ft. Meyers, near the site of today’s Pentagon. As it happened, the crash took place at 5:18 pm on September 17, 1908 (today in aviation history) in good weather in front of a crowd of over 2,000 who had gathered to see the Wright’s aeroplane, which was being demonstrated to the US Army for possible purchase per an Army contract.

On take off at 5:14 pm, the plane settled briefly back to the ground after flying about 40 feet, skipping off the earth. Some surmised that when the plane struck and recovered to continue flying, the left side, nine foot diameter propeller may have grazed the ground, cracking it. The plane had then flown four circuits around the field at an altitude of 150 feet, performing perfectly.

When the propeller suddenly broke, there was no warning. One of the blades was thrown 60 feet away. The plane lurched first upward sharply, gaining about ten feet of altitude. Amidst the violent vibration, Orville switched off the engine, but not before unbalanced propeller tore its mount and twisted to cut one of the guy wires that braced the tail. Lacking the necessary support, the vertical tail then fell sideways at an angle, serving like as the equivalent of an inadvertent rear stabilizer that pushed the nose down sharply. The plane angled nearly vertically down at the ground. With the engine shut off, Orville was able to establish a downward steep glide by pulling back on the stick as hard as he could. Nonetheless, he could not recover.

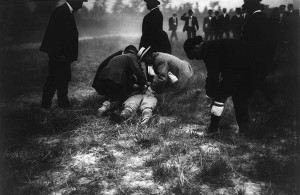

The Wright Flyer hit nose first at an estimated speed of 40 mph. Immediately, it crumpled forward in a cloud of yellow dust and dirt. The impact threw Wright and Lt. Selfridge into the forward guy wires and supports. Amidst the wreckage, Orville remained conscious, tangled in the wires, while Lt. Selfridge was unconscious, the gasoline tank and engine having fallen on top of him. While Orville suffered a broken thigh bone, some damage to his hip and few broken ribs, Selfridge’s head had impacted the vertical frame of the Flyer, fracturing his skull. Neither man wore any head protection, though Wright wore his trademark hat. This proved to be a fatal mistake for Lt. Selfridge — had he worn some sort of helmet he would have likely survived.

Chaos After the Crash

In an instant, the crowd surged forward with a yell. They stampeded toward the plane and the stricken men, though it was unclear what their intentions were. Perhaps they would have stripped the wreckage, perhaps they would have tried to drag the men from the plane, injuring them further. A fast thinking Army officer saw the danger at once and ordered his unit, a mounted cavalry unit on horseback, to charge forward and intercede. Within yards of the plane, the crowd and the mounted cavalry met and amidst the jostling, many were bruised and battered. When some tried to push through, the officer yelled to his men to ride them down if necessary — it appeared to do the trick and the mass hysteria and chaos subsided into an uneasy balance.

Both men were carefully removed from the wreckage. Quickly, they were rushed to the nearest hospital. Orville would spend the next seven weeks recovering from his injuries. However, Lt. Selfridge would not recover. That night at 8:10 pm, just three hours after the accident, he succumbed to his injuries. He was buried with full military honors in nearby Arlington National Cemetery, within sight of the crash site.

Investigation and Recommendations

After the accident, Lt. Frank P. Lahm returned to the field to begin an evaluation of the crash. Based on his work, the US Army decided that all Army aviators would thereafter be required to wear protective helmets. Lacking an aviation-specific design, the Army would use start with something similar to a football helmet with extra padding added. Thus, Lt. Selfridge’s life “was not sacrificed in vain” since countless later military aviators have been saved from serious injury by their flight helmets. The accident demonstrated the truly dangerous nature of early aircraft. Fragile, under powered and difficult to fly, they were death traps.

As a result, many more of the Army’s early aviators perished in crashes. Today, even if the risk of military aviation is now far better managed than ever before, military aircraft operations are inherently dangerous. The reason is simple — as a basic rule, stability is the enemy of maneuverability. Thus, a safe, stable aircraft is an easy target in battle. Further, when the goal of the design is to optimize performance, the engineering margins are cut razor thin. Even a few pounds saved matters — a lot. And finally, military aviators are routinely required to fly demanding maneuvers, often at extremely low or high altitudes, at high speeds, and to the very limits of an aircraft performance, something that a commercial airline pilot would simply avoid.

Aftermath of the Crash

In the end, the accident did not dissuade the Army from its new found commitment to aviation. Gen. Luke E. Wright, the Secretary of War, noted, “It is a very sad happening and one to be deeply regretted. I see no reason why this accident should give any serious setback to the experiments in aeronautics being made by the army. When Mr. Wright recovers, if he desires to try again to fulfill the contract, the opportunity will be open to him. As I understand, the accident was due to a constructural (sp.) flaw and not to a faulty principle, but this is something which will be cleared up after an investigation and a report are made.”

Sadly, Lt. Thomas Selfridge was the first military casualty in the pursuit of powered, heavier than air flight. He would not be the last either.

One More Bit of Aviation History

In 1947, the memory of Lt. Thomas Selfridge was honored by the US Army in the naming of a new airfield — Selfridge Air Force Base, located in Harrison Township, Michigan, just a few miles northeast of Detroit. Today, the field continues to be used by the Michigan Air National Guard and, as such, has been renamed Selfridge ANGB. The field is home to the 127th Wing, flying a composite mission involving KC-135 Stratotankers and A-10C Thunderbolt II ground attack aircraft, which are assigned to the 107th Fighter Squadron, the direct descendent of one of the oldest squadrons in US military history — the venerable 107th Aero Squadron of 1917, which took part in World War I.

Today’s Aviation History Trivia Question

If Thomas Selfridge was the first military casualty, who was the second and how did he die?

Ralph Johnstone, killed in Denver, Colorado, on September 17, 1911.

LT George Kelly was killed in May 1911, making him the second fatality. Base in TX named after him.