Published on December 18, 2012

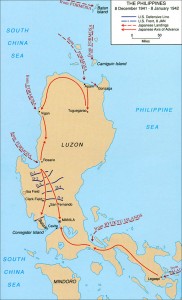

The first weeks of the war in the Pacific were desperate. Pearl Harbor was struck on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, and within hours, the Philippines was also under attack. The US Army Air Corps had a large fleet of aircraft based at Clark Airfield on Luzon, including 72 P-40 Warhawk fighter planes and 35 B-17 Flying Fortresses. The Japanese certainly understood the potential of air power — in fact, their Pacific strategy was largely based on the use of aircraft to bomb and strafe Allied forces into defeat. Thus, they committed over 450 aircraft to the battle for the Philippines. What was worse, they struck and caught the American command by surprise — even as the communications were lit with requests for confirmation and information regarding Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Half of the American fighters were destroyed on the ground.

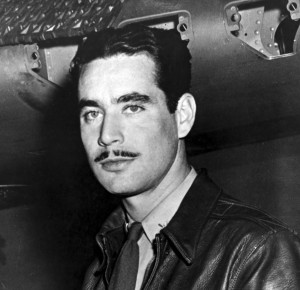

Yet from the ashes of the first days of conflict, America would celebrate its first ace of World War II — a man named Boyd “Buzz” Wagner. As for the nickname “Buzz”, that came from the fact that he was known to buzz airfield buildings so low that he could knock tiles off the roofs.

Against All Odds

By December 10, 1941, the Japanese air assault had brought the number of P-40 Warhawks in the Philippines so low that the Japanese now enjoyed something nearing a 20-1 advantage in sheer numbers over the American forces. Concurrently, the Japanese had landed ground forces at Aparri, at the far northernmost tip of Luzon, and at Vigan, which fell along the northwest coast. Within days, the first land-based Japanese fighter planes were arriving at a new airfield at Vigan.

Although the American air commanders had ordered the remaining B-17s to fly south out of harms way and also ordered that the last 22 P-40 Warhawk and 8 P-35 fighters be restricted to reconnaissance missions so as to preserve their numbers. In the meantime, Japanese bombers were striking with heavy escorts of between 100 and 150 Japanese Zeroes. Everyone, from the commanders to the pilots and ground crews, felt that it was just a matter of holding out long enough until US reinforcements arrived to relieve them. Sadly, though they didn’t know it at the time, no reinforcements were on the way.

On December 11, one of the pilots, 1st Lt. Boyd “Buzz” Wagner, was assigned to fly a reconnaissance mission over Aparri — it would be a flight that was 225 miles each way. He was to take off and fly a route to report on enemy movements and any additional landings that might be underway. Flying alone, it was hoped that he would slip in and come away without being intercepted. Arriving at Aparri, he encountered the Japanese invasion fleet and, flying low, he came under fire from a pair of Japanese Naval destroyers, whose fire he evaded. Nonetheless, the Japanese called in a flight of five Mitsubishi A6M2 Zeroes to intercept him. As a result, Buzz Wagner was bounced from above by five enemy aircraft — the closed from above and behind as he dodged the enemy flak.

Thinking quickly, he dove and, looking back, realized that his P-40 Warhawk could outrun the Japanese Zeroes in a dive. Leveling off, he quickly assessed the relative speeds and realized too that the Warhawk could also escape running flat out in level flight. Soon he was far away and looking back, could see the five Japanese Zeroes turn toward their base. He wheeled around and, staying low, flew toward them. With his superior speed, he soon closed the distance. This time, he was the hunter — and was not spotted as he closed in. He took careful aim on the first aircraft — pulling the trigger, he shot it down. Instantly, he kicked the rudders and turned toward the second aircraft. Again he fired and the second Japanese airplane fell into the sea.

Peeling off, he located their airfield and dove in to attack. Many enemy fighters were lined up on the small runway and he made two passes, setting fire to ten of the aircraft. He turned to fly back to Clark Airfield, however, the last enemy aircraft from the earlier engagement were still around. Suddenly, he realized that they were closing in from behind at high speed. Chopping the throttle, he dodged with P-40 as it slowed rapidly. The two Japanese Zeroes misjudged their attack and overshot, racing past him with too much speed. Now, they were the ones in front of his guns. With a quick kick of the rudder he lined up again and fired, downing one and then the other in quick succession. For a second time, he turned toward home. His credit for the day was fourteen enemy aircraft, four of which were shot down in the air.

Becoming an Ace

Soon thereafter, other reconnaissance reports confirmed that there were at least 25 Japanese airplanes parked at Vigan. The American commanders decided to fly a surprise raid of their own and assigned Buzz Wagner to lead the flight. He selected another two highly skilled pilots, Lts. Allison W. Strauss and Russell M. Church, Jr., to fly the mission with him. Two of the three planes were loaded each with six 30 pound bombs — the other would serve as an escort fighter.

At dawn on December 16, the three pilots took off, each in a P-40 Warhawk. They flew to Vigan and came in at low altitude from offshore so as to avoid early detection. Without pause and as planned, Lt. Strauss climbed high to provide top cover as the other two planes swooped in on the parked Japanese aircraft at the field. Buzz Wagner was the first overhead and dropped his bombs into the center of the enemy aircraft. As he peeled off, the second P-40 Warhawk came diving in.

Frantically, the Japanese anti-aircraft gunners manned their guns. Immediately, the Japanese fire had its effect as Lt. Church’s P-40 Warhawk was hit and caught fire. Over the radio, Buzz Wagner ordered him to break off and escape to bail out — yet Church instead dove down at the enemy airfield and lined up to attack, even as flames consumed his aircraft. Flying over the center of the parked planes, he released his six bombs, scoring six direct hits. Then flew straight ahead and away from the field. Soon thereafter, overcome by the fire, the plane slanted off and crashed in flames.

Buzz Wagner returned to the Vigan airfield and strafed the remaining enemy aircraft, braving the intense anti-aircraft fire. Flying parallel to the runway, he noticed a flash of something that quickly disappeared under his wing. To get a better view, he rolled inverted — even if he was at extremely low altitude. With a clear view, he realized that one of the Japanese Zeroes was taking off directly alongside him. Thinking quickly, he chopped the throttle, kicked his plane back upright and shifted over in a skid behind the Japanese plane — with another burst of fire, he downed it as well.

The two surviving American planes returned to Clark Airfield. Their credit for the day’s work was never determined, but it was probably at least a dozen planes on the ground plus the one that Buzz Wagner downed just after it took off. With his fifth kill officially credited, Buzz Wagner became the first ace of the American forces in World War II.

His Final Combat Mission

After the mission to Vigan, Buzz Wagner was assigned to yet another reconnaissance flight. It was December 18, 1941 — today in aviation history. Sadly, once again, the Japanese gunners proved their worth. As he made his reconnaissance pass, the Japanese opened fire. One of their heavy AAA guns fired a shell that exploded directly in front of his P-40 Warhawk. The canopy and nose were showered in shrapnel, injuring Buzz Wagner badly with bits of metal in his face and chest. One metal shard pierced his left eye. Bloody and in extreme pain, with vision from but one eye, he flew back to Clark Airfield. Landing successfully, he was transferred out of the Philippines to a hospital for recovery.

Buzz Wagner would return to combat, but not in the Philippines, which fell just days after Wagner was evacuated for surgery. After recovery, he was ordered to take charge of all fighter aircraft in New Guinea. He would fly the Bell P-39 Airacobra and in that plane, in a single mission later in 1942, he would down yet another three enemy aircraft. With eight kills to his credit, he was ordered back to the USA to perform training duties — over his objections. The War Department considered his skills as America’s first ace to be best used in training others to fly combat. He would never see combat again.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Buzz Wagner died in an aviation accident just a few months later. On November 29, 1942, when flying a brand new P-40K Warhawk from Eglin Field in Florida to Maxwell Field, Alabama, his plane simply disappeared. It took six weeks to find the wreckage of his airplane and his remains — the reason was that it was 90 degrees off of his planned course, many miles away. He would be buried with full military honors in a huge funeral attended by between 15,000 and 20,000 Americans. His funeral and burial were covered by LIFE Magazine — and so marked the end of America’s first ace of World War II.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The P-40 Warhawk was made famous flying in the defense of the Philippines and with the AVG in the Pacific. As well, it served duty in North Africa, England and elsewhere. Who was the leading ace who flew the P-40 Warhawk?

Was it General Joel Paris?

Terrific story. So sad Buzz Wagner did not live to see the end of the war. You mention the story on his funeral in LIFE. Is that where the photos from the story came from? I am specifically interested in obtaining rights to use the photo of the planes at Clark Field. Any help would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you so much.

Group Captain Clive Caldwell, DSO, DFC and Bar RAAF.