Published on February 4, 2013

Not every aviation pioneer was successful — in fact, many were not, with some even dying on the long and hard road to proving that man could safely fly. Francois (Franz) Reichelt was just such a man. His death was tragic and, though most consider his leap of faith to be little more than folly, in fact, he was on the right path — but only with years of further work would that be known. His invention was revolutionary — a backpack-mounted, non-rigid parachute for use by pilots.

Reichelt’s Past Work

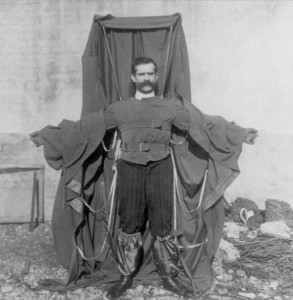

Reichelt had arrived in Paris from Austria just five years earlier to set up shop as a tailor for men’s and women’s clothing. These were valuable skills for an inventor, particularly one who was focused on perfecting a pilot’s parachute. His idea was to design a system that could be worn like a garment, part of which involved a backpack into which a silk, folded parachute would be packed with care. Whereas others had been working on a parachute that involved a concave canopy that would inflate above and slow the aviator’s fall, held in shape by a wooden frame, these proved too bulky for use in an aeroplane. Reichelt’s design was radically different, being more like a wingsuit/parachute blend.

Reichelt had been testing his designs for many months using mannequins. He would suit them up, then, pulling the parachute out, he would manually throw them off tall buildings. Finally, he had gotten permission to test his designs at the Eiffel Tower where he threw his mannequins off of the first platform level. Most of the time, the mannequins would hit the ground with a solid thud. Once, however, the parachute system had worked perfectly. The mannequin had glided down to a perfect landing.

Having observed that success, Reichelt took many months to make modifications to his design to capture what he learned based on that experience. Satisfied with his new design, he petitioned for the right to test it again from the Eiffel Tower. This time, however, he intended to operate it himself, recognizing that the position of the body was important to the success of the device.

Official Reticence

Having seen his previous experiments, however, the Paris Police were not favorable toward allowing him to test it personally. It took weeks of petitioning to gain their approval, though it appears that the police thought that they were approving more tests with mannequins when they gave the go-ahead after long negotiations. In the meantime, Reichelt’s friends tried to stop him from testing the device himself. He was adamant, however. He stated that it could only work with a man, not a mannequin and without safety cables or other “shams” that would erode the success of the test. He trusted his new apparatus completely.

Finally, on the morning of February 4, 1912 — 101 years ago today in aviation history — Reichelt was ready. The police roped off an area to hold back the small crowd that gathered including members of most of Paris’ newspapers. A photographer and two cinematographers were hired to be on hand and capture the jump on movie film. At the base of the Eiffel Tower, one of the policemen realized on seeing Reichelt in his parachute suit that he was going to jump himself. He tried to prevent him from mounting the Eiffel Tower, arguing that it wasn’t approved. In response, Reichelt showed the police permission order, which left it unsaid whether a mannequin was required — thus, he was approved for the test. The policeman let him through and Reichelt turned to the assembled crowd and called, “A Bientot!” before heading up.

The Tragic Jump

Reaching the first platform, Reichelt was 80 meters high. A jump from there would be fatal if his system failed, yet he was confident in his design. Two of his friends had accompanied him, as well as the cinematographer. The other cinematographer positioned himself on the ground opposite the jump point, so as to capture the span of the legs of the Eiffel Tower and Reichelt’s leap of faith.

On the platform, his two friends tried one last time to intervene and convince him that more mannequin tests would be wiser. He waved them off and climbed onto the edge of the platform. Looking down at the ground below, he stood hesitatingly. He appeared momentarily uncertain. He said a few more words to his friends and then leaned forward as if jump, but then pulled back. Twice more he leaned into it but then pulled back again abruptly. Finally, he simply stepped off forward and fell face first off the platform like an ungainly diver, stretching his arms out to engage the parachute. It had taken a full 40 seconds for him to make the leap — it was 8:22 am.

Instead of deploying properly, the wind from the accelerating fall wrapped his parachute around him as he fell. His head was aimed straight down toward the ground. A gasp rose from the shocked crowd. In the last ten meters, it seemed that his parachute finally started to deploy properly — perhaps if he had jumped from higher up it might have opened all the way, though perhaps not. In modern terms, it was a crude design and did not appear to have the right features. As it happened, he was already too close to the frozen ground below for it to matter. With a sickening thud, he hit the ground. He died instantly from the impact. His head made a dent in the ground at the base of the tower that authorities measured at 15 cm deep, which they dutifully reported to the assembled news reporters.

After the Jump

His body was carried to Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital at 149, rue de Sèvres, where he was pronounced officially dead (though the reality of that had been obvious from the moment of the first impact). Then his body was carried to the police station on Rue Amélie. Awhile later, it was carried to his third floor apartment at 8 rue Gaillon. Later, an autopsy report was issued by the hospital. Among the findings, both his right limbs were crushed, his spine was shattered, his skull splintered, he was bleeding from the mouth, ears and nose and his eyes were wide open, “dilated with terror”.

Amazingly, the doctor’s also determined that probably as he had fallen off the top of the first platform, he had suffered a massive and fatal heart attack, probably brought on by the stress of the moment (this latter bit of news was not reported widely for over 95 years after his death)!

The News Coverage

The following day’s news carried the story across Paris. Headlines varied but were to the point:

L’Expérience du Parachutiste a Fini Tragiquement

The Experience of the Parachutist Finished Tragically

L’INVENTEUR REICHELT S’EST TUÉ HIER

en se laissant tomber de la première plate-forme de la Tour Eiffel

THE INVENTOR REICHELT KILLED HIMSELF YESTERDAY

in throwing himself from the first platform of the Eiffel Tower.

Over the years that followed, coverage typically discussed the tragedy in terms that made Reichelt appear to be a foolish visionary who needlessly took his own life. While it is clear that he could have benefited from more tests — his friends were right in that regard — he was also right in another way, that the only true way to know whether the apparatus worked would be to try it out “live”. It was at that point, like it or not, that the ultimate test would have to take place.

Sadly for Francois Reichelt, he died attempting to prove his invention. A body suit that formed the basis of a parachute would develop over time, but only many decades later. As for backpack-mounted non-rigid silk parachutes, they would be issued to some aviators during World War I in the last months of the war. By the 1920s, they were commonplace. Thus, in the end, Reichelt’s vision was correct, it was just that his design was still wrong.

One More Bit of Aviation History

How far we have come since the days of experimenting with parachutes. Nowadays, even beyond the amazingly maneuverable parachutes one sees in use in military and sport, there are also the new generation of parasails — seen here in a video shot at Col de la Forclaz, near Annecy, France. The beeping is a vertical speed indicator, when it increases in pitch, it indicates that the parasail pilot is in a thermal or updraft, rising upward perhaps from the wind against the slope of the mountainside.

If you get it right, you can fly all day along the ridges, sitting in your small strap of a seat with the beauty of nature around you. In other words, once you jump off the cliff, you aren’t looking down trying to spot a landing place — rather, you look up because that is where you are going, higher into the sky, to touch the face of God.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Also in February 1912, another person made a parachute jump — this time succeeding. That was all the across the Atlantic, however, in New York, and thus the news of it would not reach France for weeks to come. Who made the jump and where was it accomplished?