Published on March 13, 2013

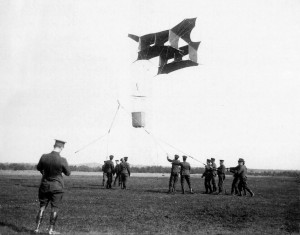

“High Upon a Kite. The No. 1 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps carried out an extensive series of experiments with kites at Farnborough, on Tuesday, and in one case an officer and two men were carried to a height of 2,000 feet.”

One hundred years ago today, this small snippet appeared in the then current issue of Flight, the newsletter of the Royal Aero Club in Great Britain. The idea of manned, or man-lifting kites sounds rather extraordinary to the modern reader, but in fact, it is an age-old practice that dates back to the Chinese, who first used kites as a way to execute prisoners. Later, the Japanese also used man-lifting kites for a variety of purposes, including such mundane tasks as lifting men and supplies to the top of buildings during construction projects, a practice that dates from the 1700s. In Britain, the idea of military uses of kites had taken hold in the 1880s and 1890s. By 1904, the War Office had active contracts with the famous aviator, Samuel Cody, who had achieved flights by that point as high as 1,600 feet, using a 4,000 foot long cable. By 1913, however, kites were falling out of use due to the emergence of airplanes as better, more flexible reconnaissance machines — and due to something else. In fact, it wouldn’t be the airplane that ultimately would replace the man-lifting observation kite, but rather something completely different and unexpected.

Development of the Cody Bat Kites

In the 1900s, Samuel Cody had worked on a new man-lifting kite concept called the Bat. Fittingly, its shape included bat-like spars and stretched, dark fabric. The “Bat” look evolved to the point where modern filmmakers depicting Bruce Wayne’s alter ego would be proud. Yet Cody’s Bats far predated any comic book heroes. They were, in two words, both useful and terrifying — useful to the officers on the ground in need of information and terrifying for those who were standing in the wicker basked suspended below the Bat and carried aloft into the skies.

In fact, it was through kites, not aeroplanes that Samuel Cody first made his name. In the years before the first flights were made in Europe, there were few options for anyone seeking to experience flight. Samuel Cody, an American who had become a British citizen, pioneered a new use of kites as a way to sail aloft, similar to balloons, but tethered to the ground or to a vehicle of some sort so the kite “pilot” (who was really more along for the ride than actually piloting the kite itself) could move from place to place. To prove the concept and gain the respect of his peers, Samuel Cody flew one of his own kites across the English Channel, pulled behind a small boat. The attention of the Royal Navy and the Royal Astronomical Society followed quickly. Samuel Cody was then awarded with a new military title and role, as the Chief Kite Instructor.

Later Cody Bats reached an altitude of 2,000 feet in tests, carrying up to three men in the air in the attached basket. One reached over 3,440 feet, a record, carrying Lieutenant Broke–Smith into the skies. If one were to consider what the ride might be like, it would clearly be on a par with skydiving, except that it might last hours, hanging there in the air, hoping that the wind didn’t abruptly shift or die down, pondering how easy it was to get injured at landing. If you’ve ever flown a kite yourself, it is obvious that landing one gently is not the usual ending for the day’s flights at the beach, even if various stabilization panels, topsails and multiple kite systems added greatly to the stability of the overall apparatus.

Other Kite Designs in Europe

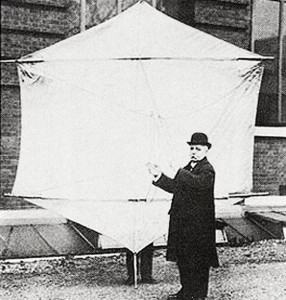

Interestingly, Samuel Cody was not the only man who had developed kites for observation and flight. Another earlier kite experimenter was Baden Baden-Powell and his hexagonal-shaped “Levitor” kites from the 1890s; these were supposed to lift a single man up for aerial observation during military operations. The man was essentially “crucified on the kite”, however, and the contraption was far from safe. Baden-Powell’s kites, nonetheless, got the approval of the War Office for use in the Boer War and several were sent to South Africa. The war ended, however, before they could be used. The same kites were then later used by Guglielmo Marconi in 1901, who used a “Levitor” design to raise an antenna up to an altitude of 400 feet so as to facilitate the first successful wireless communications across the Atlantic Ocean.

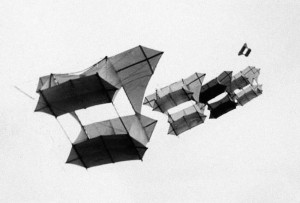

The famous Norwegian Arctic explorer, Roald Amundsen also worked on man-lifting kite designs in 1909, working with Einar Sem-Jacobsen to perfect a series of box kites that were strung out in a row (Samuel Cody had also experimented with the same stabilization concept). Ultimately, however, even if Einar Sem-Jacobsen’s kites worked, even testing them by lifting Amundsen himself, the polar explorer decided that he would not take them into the Arctic after all.

The End of Kite Development

While most historians like to present that it was the airplane that truly ended kite development, that would be a wrong statement. Indeed, something else took over the man-lifting kite, something far more reliable and easy to deploy and which didn’t rely on uncertain winds to remain in position. It was, of all things, the observation balloon. By the middle of the Great War — 1914-1918 — observation balloons were in use on both sides of the front lines.

Artillery was the great killer of the war — far more than rifle shots, machine guns, aerial bombing or strafing, or even poison gas, which was in common use. It was the heavy artillery that proved to be the deadly killer of that era of trench warfare. From the observation balloons, observers could relay targeting information to artillery units and correct the aim to fire for maximum effect. Of course, the only problem with observation balloons was that they too could be shot down — and some pilots soon became quite expert at destroying the balloons. Both sides had an answer to that, however, which was to surround the balloon with anti-aircraft artillery. But that’s another story….

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Samuel Cody built the first aeroplane in English history, but he got his start with man-lifting kites. Who were his primary helpers in the kite design work that he did starting in 1899 and continuing on into the first decade of the 1900s?