Published on April 6, 2013

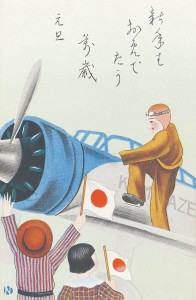

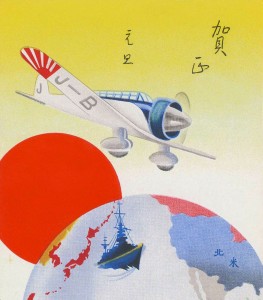

Some time ago, while reviewing aviation postcards from the 1930s and 1940s, we came across a curious set of Japanese New Year’s holiday cards labelled “Kamikaze” that showed a Japanese pilot climbing into the cockpit of what looked a bit like a Mitsubishi B5M “Mabel” bomber. In the foreground, two children waved their arms and a flag. Strangely, the label on the side of the fuselage was in English. Another image showed the same plane flying from Japan toward the USA while a warship steamed eastward underneath — again it was labeled “Kamikaze”.

It seemed strange that the sad story of Japanese aviators sacrificing themselves in the last year of World War II by crashing their planes into Allied ships would be the subject of a New Year’s celebration card. We wondered also at the artwork of the cards, which was bright and positive — how could this be from the closing months of the war? Something was amiss, out of step with the desperate times of Japan in the 1944 and 1945 years. Also, the use of English on the side of the plane also made no sense for what we assumed to be Japanese propaganda piece. With growing interest, we researched the cards to find out just what they were and what their context truly was — and thus, we discovered an incredible story dating to 1937 that has been largely ignored in aviation history.

In fact, we had misunderstood the meaning completely. The “Kamikaze” cards were not from 1945 nor were they printed as propaganda pieces to celebrate the suicidal attacks of Japan’s dying military regime. Rather, they were designed to celebrate the New Year’s holiday of 1937. Surprising the Kamikaze referred to something extraordinary that had happened just four years before Japan would attack Pearl Harbor. Two Japanese aviators, pilot Masaaki Iinuma and navigator Kenji Tsukagoshi, would complete one of the greatest long distance flights in history.

A Record Flight Nearly Lost in History

On April 6, 1937 — today in aviation history! — the two men took off from Tachikawa Airfield, Japan, en route to London, England. Their plane was custom-built and developed from a long range reconnaissance plane created by aeronautical engineer Fumihiko Kono and based on the inspiration of the Northrop A-17. Built by Mitsubishi, later models would carry the designation of Ki-15. The second prototype of three built in 1936/1937 was acquired for the record flight by a Japanese newspaper and registered as a civilian plane. It carried the name Kamikaze on one side in English and on the other in Japanese. It also displayed J-BAAI, the internationally recognized code that was fitting for a flight to Europe. Weirdly, the tail included an image of a leaping tiger, weirdly and coincidentally nearly identical to the one later employed by the American Volunteer Group, the “Flying Tigers”. The wing tips bore the Rising Sun symbol normally associated with Japan’s military, despite that it was a civilian flight.

After departing Tachikawa Airfield, the flight of the Kamikaze proceeded southwest and then looped across the southern coast of Asia, crossing India, and then proceeding directly to the Mediterranean before turning northeast to head across Europe to London. The goal was to connect Japan and England in honor of the coronation of King George VI, which was scheduled for May 12, 1937. Along the way, the Kamikaze would stop at Taipei in China, then continue on to Hanoi and Vientiane in Indochina before setting down at Calcutta in India. Thereafter, the Kamikaze would fly to Karachi, India, and then across the southern coast of Persia and up the Arabian Gulf for a stop at Basra, Iraq. The plane would then fly up the Tigris and Euphrates to Baghdad before turning west to head to Europe and England.

The first stop in Europe would be along the Mediterranean in Athens, Greece. From there, the plane would fly to Rome, Italy, and then onward to Paris, France. At each successful stop, the crowds would grow and soon the pilot was being called the “Japanese Lindbergh”. The flight would culminate in a mid-afternoon arrival at Croydon Aerodrome in London, England. The landing there would be described by observers as “the bounceless plop of a mashed potato”, terminology that is questionable given that a review of the actual video of the landing demonstrates it to be a perfect three-pointer!

Overall, the flight had covered 9,542 miles and taken a total of 94 hours, 17 minutes and 56 seconds. The flight time, not including fuel and rest stops, added up to just 51 hours, 19 minutes and 23 seconds. It was record that would be recorded by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the awarded for a Japanese flight. The achievement compared more than favorably with the time set by England’s own de Havilland Comet in the 1934 MacRobertson Air Race, which had made the flight to Australia 11,000 miles in 70 hours, 55 minutes. At the time, European views of the Japanese were colored by racism and the expectations were that Japanese abilities and aircraft designs were very poor. Thus, many speculated that the navigator, Tsukagoshi, whose mother was English, had enabled success by bringing Western racial advantages to the flight; others attributed a European parent to Iinuma, which was entirely false — such were the bizarre racist views of those times.

At the arrival ceremony at Croydon, the Japanese Embassy in London had arranged for a group of local Japanese school children to be on hand to greet the aviators with flowers and flags, yet the girls were nearly trampled once the engines were shut down, as the English crowd rushed forward to the airplane in their excitement. The distance flown was 9,542 miles, all without mishap or mechanical trouble — testimony to the quality of Japanese aviation engineering that was largely ignored by the world media and military men who reviewed the flight.

On May 12, 1937, the two men took the Kamikaze up to film the coronation parade from the air. Two days afterward on May 14, they departed for Japan, flying the same route back but at a only barely more leisurely pace (taking just six days!). They arrived in Osaka on May 20 and delivered the films of the coronation event to their employer, the media outlet Asahi Shimbun.

Ultimately, the unbelievable record of these two men would stand for over three decades until finally broken by a US Navy P-3 Orion. That’s not bad for a single engine aircraft of the late 1930s!

Looking Back and Recovering History

Looking back, we recognize now how the amazing achievement of Iinuma and Tsukagoshi was nearly lost in history. Seven years later, a desperate military regime, the Imperial Japanese Government, struggled to defend that nation’s homeland in a losing war. As the island hopping campaign of the US advanced steadily up toward Japan itself, there seemed few options left to turn the tide. The Japanese Air Force’s final contribution was the “Kamikaze”, a suicide attack strategy by its aviators who were ordered to crash their planes into the American ships in hopes of sinking them. Such attacks were out of sync with the Western understandings of the value placed on each human life yet they were undeniably effective, striking and sinking many ships in the final months of the war.

Thus, the shocking practice of the Kamikaze consumed the meaning of the original term, “Divine Wind”, which referred to the cyclone that had wiped out a Mongol invasion fleet hundreds of years before, thereby saving the Japanese from a devastating invasion and occupation from mainland China. From that origin, the name for the record-setting flight of Masaaki Iinuma and Kenji Tsukagoshi was selected, long before Japan went to war with Europe and the United States, joining Hitler’s Axis powers in their quest at world domination. With that later, unfortunate redefinition of the meaning of the term Kamikaze, the extraordinary achievement of the two Japanese airmen was crushed by the weight of history. Their Japan of 1937, while at that time ruled by the Imperial Government and involved in a terrible war in China, was still engaged positively with the West. Their flight was a gesture of peace amidst the darkening skies of a coming war that would consume the world.

We can only hope that in writing this article we can help contribute to a more positive understanding of those years before Pearl Harbor. The flight of the Kamikaze should no longer be overshadowed by the later meaning of the word. In any case, with the passing of nearly seven decades since the end of World War II, the Japan we see today is a strong force for peace in today’s unstable world. Iinuma and Tsukagoshi would have likely been proud of the result.

Video of the Arrival of the Kamikaze at Croydon

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What ultimately became of the “Kamikaze” aircraft and the two Japanese aviators, Masaaki Iinuma and Kenji Tsukagoshi?

I wonder at your misinterpretation, especially since the plane and ship are both facing east. Given Yamamoto’s opposition to the attack might this have been construed as a subtle hint that American forces failed to catch?

The plane and ships are faced east, even though the record-setting flight was heading west to London. That fueled the misinterpretation of the cards as being a late war construction, perhaps to celebrate the New Year of January 1944. Since the cards turned out to be from 1937, that interpretation was clearly erroneous, hence our doing the research and writing the article. While there were political issues between the US and Japan, the attacks on Pearl Harbor were still four years in the future. There was nothing there as a subtle hint to “catch” — it was simply that the designer wanted to show the plane heading left to right (thus appearing faster, a graphic design trick), and that it was a global scale, intercontinental flight. In any case, three years later, in 1940, there were more than enough people in Washington who suspected that war was inevitable with the Japanese, hence the American military build up that had already begun by that point.

That English ‘all over’ grass field makes the aircraft look like a model. Great story !