Published on May 8, 2013

The plane was purpose-built for the flight, extensively modified from a proven design of the Levasseur PL4 reconnaissance seaplane and redesignated as the Levasseur PL.8. Its huge bulk carried thousands of pounds of gasoline, enough to hopefully achieve a singular goal — to claim the Orteig Prize. That award offered the princely sum of $25,000 as an incentive to the aviator or aviators who could first link Paris and New York in a single flight, in either direction. The men who took up the challenge were Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli, two former combat pilots who were the second and third highest scoring French aces from the Great War of 1914-1918. Their plane, nicknamed “L’Oiseau Blanc”, or White Bird, represented the hopes of world peace in the form of the dove of peace. With high hopes, the men took off today in aviation history, on May 8, 1927.

They were last sighted leaving Ireland heading northwest out into the open Atlantic. What happened next remains one of aviation’s greatest mysteries. Put simply, they never arrived in New York and neither man, nor the plane, have been seen since. In short, they simply disappeared.

The Plane

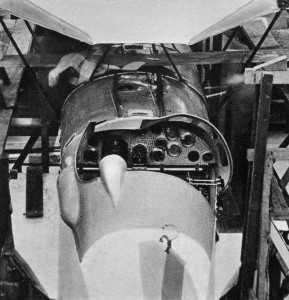

Nungesser and Coli had carefully developed the plane in close coordination with the Pierre Levasseur Company in Paris. Personally working with the designers, the men made numerous changes to the existing PL.4 seaplane design. Principally, the fuselage was widened, allowing the pilots to sit side-by-side and enabling three huge fuel tanks carrying 1,056 gallons of gasoline to be mounted between the biplane wings behind the engine firewall. A single 460 hp W-12 Lorraine-Dietrich engine was installed (two engines only doubled the number of failures that might occur on such a long flight) after it had been bench-tested and “broken in” by running at low to medium power for 40 hours.

Numerous innovative features were developed for the airplane. The most important of these had to do with the landing gear and fuselage. The wheels were designed to fall away after take off, rather than retract or hang unneeded under the fuselage for the long flight across the Atlantic. The savings in drag enabled the plane to fly faster, carry more fuel and be lighter weight. For landing, the fuselage was fashioned into a flying boat hull so as to enable a water landing — it served also as its own life raft if the two aviators came down in the open ocean.

Fittingly, Charles Nungesser’s wartime personal insignia was painted on the rear of the fuselage — it was a skull and crossbones, flanked by a pair of candles and a coffin, all of which were emblazoned on a black heart. If the new technology of aviation was to spread the message of peace and hope, the thought was, who better to fly it than two former wartime pilots?

The Flight

When the men took off at 5:17 am on May 8, 1927 — today in aviation history — they had great difficulty at first. The plane was so heavily loaded that as it lifted off, it couldn’t quite fly. It settled back down on the runway at Le Bourget in Paris, before it took off again, this time slowly risng into the early morning air as the two ace pilots gingerly kept it up as the speed slowly increased. They managed a low and slow climb — it was the best that could be done as the crowds they left behind cheered madly.

They were next seen crossing the French cast and heading out across the English Channel. Four French Armée de l’Air pursuit planes flew in formation as an escort under Captain Venson. It was a powerful tribute, but once L’Oiseau Blanc crossed over the English Channel, they broke off and returned to their bases. Shortly afterward, a British submarine spotted and logged the passage of the plane overhead as it headed toward the English coast. It was then spotted and logged over Ireland before one last observer reported the plane’s passage northwest out into the Atlantic Ocean.

It was the last anyone saw of the plane — even to this day.

The Mystery

There are many competing theories concerning the fate of L’Oiseau Blanc. Critically, the plane, traveling the Great Circle route across the North Atlantic, was far to the north of the established sea lanes. If an engine problem had developed, the two aviators could have set it down in the water, though the condition of the waves might have made that difficult. Once alighted on the water, the waves would likely tear the wings off the fuselage and tail. They might have floated awhile, but without ships in the water nearby, their rescue was essentially impossible. In any case, no fuselage “boat” was ever found.

Many people in Canada and Maine came forward at the time with reports of hearing an airplane engine overhead. Many reported what they thought was the sound of an airplane engine passing overhead and disappearing to the southwest, as if navigating toward New York. In fact, the two men had planned the trip exactly that way, having planned on culminating their flight with a landing on the Hudson River right at the base of the Statue of Liberty. In deference to the multiple reports of hearing the engine noise overhead, it seems that many could well be accurate — if not “sightings”, they were likely “hearings”.

Plotting the “hearings” gives some evidence that the plane was running desperately late, having likely been dogged by headwinds the entire way. If so, based on the times of the “hearings”, it seemed that they must have come down into the forests of rural Maine. Searches by many others in the years since, including by such men as author Clive Cussler, never turned up a single trace of the plane, however. Moreover, a careful review of many of the newspapers of the era reveals that many sightings were rumors that were built up into full-fledged false stories in hopes of selling newspapers.

One Parisian paper even fabricated the safe arrival of the two men in New York. The Parisian response was a complete loss of faith in the publication since journalism, after all, should be at least somewhat truthful and accurate. Ultimately, the lost sales resulted in the bankruptcy of that paper. Most writers at the time claimed that L’Oiseau Blanc had crashed or landed in the Atlantic Ocean — a theory that remains widely accepted even today. As the men had no weather reporting for the majority of their over water trip, anything could have happened. Had the pilots been downed in bad weather? Had the plane’s fuselage floated as planned? Had the wings torn off in contrary seas? Had the fuselage swamped and sunk? Had gotten lost and and flew into the center of the Atlantic? It is impossible to know.

Aftermath

Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli were sorely missed in France. They were two of the country’s greatest military pilots. France mourned their disappearance, hoping that some bit of news would reverse a much-feared reality. But it was not to be. Two weeks later, Charles Lindbergh took off from New York and flew to Paris, taking the Orteig Prize. On arrival at Le Bourget, he was worried that the French would condemn his effort as it was coming so soon after the disappearance of L’Oiseau Blanc. He was wrong, of course, and the French celebrated him and his airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, with wild abandon.

As for Nungesser and Coli, perhaps one day, an errant hiker will come across the remnants of the plane in the woods. The engine should be recognizable due to its three banks of four cylinders each in parallel (a so-called W-12, just as a V-8 is an engine of two banks of four cylinders shaped in a “V”). Or perhaps one day by random chance, a ship with sidescan sonar will spot the shape of the fuselage and wings on the sands deep underwater in the midst of the Atlantic — if even that much is left intact, which seems somewhat unlikely.

Hopefully, the mystery of L’Oiseau Blanc will be solved one day. Maybe the two aviators did in fact manage to cross the Atlantic after all, even if they would have failed to qualify for the Orteig Prize, having fallen short of New York. Even making it as far as Canada would have been an amazing feat.

Of course, if they had indeed made it to Maine, it wouldn’t have been what they set out to accomplish, nor negate what Lindbergh did become the first person to fly from either New York to Paris or Paris to New York (which is what Nungesser and Coli were trying to do). Also, as we know, Lindbergh was the first to fly solo across the Atlantic, and, despite what the New York Times stupidly wrote in an article many years ago, it would not alter history and not change the fact that Lindbergh was the first to make it across solo by plane (paraphrasing — Nungesser and Coli = two people in the cockpit!). The truth is that two pilots named Alcock and Brown co-flew the Atlantic non-stop from Newfoundland to Ireland in 1919. Nevetheless, it would be great to know they might have at least made it even if it was to Maine still sad, however, that they did not make it alive .

An interesting article thank you. We recently visited the memorial Nungesser and Coli at Etretat, Normandy – some pictures here http://www.normandythenandnow.com/last-flight-of-the-white-bird-at-etretat/

It’s a stunning memorial at the place Nungesser and Coli last saw France.

Also posted is an old image of the original memorial blown up by the Germans in WW2. Memorial styles certainly change!

We are glad Nungesser and Coli and their bravery are not forgotten.

Can anyone tell me if the name ‘LORRAINE’ was on the rudder section when the aircraft left Paris on My8, 1927? I do not see it on any of the photos when it was leaving Paris, if the photos were from May 8, 1927. The replica on the roof of the L’Oiseau Blanc Restaurant has the word LORRAINE and other names on it.