Published on June 8, 2013

By Thomas C. Van Hare

Have you ever heard of “Missile Mail”? Yes, our Government in Washington had the rather harebrained idea of loading US Mail onto submarine-launched nuclear cruise missiles (thankfully without the warheads) and firing them off for fast international delivery. It might work, as the saying goes, but there are a couple of reasons not to do it. Just a couple. Really.

On this date in aviation and aerospace history — in 1959 — the US Post Office and US Navy combined efforts to create the world’s fastest postal delivery system. The idea was simple, though the technology was complex. First, mail would be aggregated into small containers for delivery, these would then be loaded onto a cruise missile, which would be loaded onto a submarine, which would sail off the coast and fire it to a distant destination.

On the drawing board, the dream of “Missile Mail” seemed tantalizingly within reach. With this innovative approach to mail delivery, letters could be sent to Europe within hours rather than days or weeks. But what’s on paper doesn’t always work in actual practice, so first, there would have to be tests and there were some issues to be resolved before the idea could get off the ground.

The first tests of Missile Mail proved that the practice wasn’t all that fast or cost-effective, despite the promise of the paperwork. Originating in Norfolk, Virginia, the test mail delivery package actually reached Washington, DC, many days later. It would have been faster to send it by bicycle — and certainly a lot cheaper. The Missile Mail test team, however, explained away the issue as just a demonstration problem since the mail didn’t take a direct route, but rather went from Virginia to Washington by way of Jacksonville, Florida.

That’s government, after all.

Looks Good on Paper

As it happened, the US Government and military might have done better to study history first. The idea of rocket mail — or missile mail, as the government would later call it — was not new in 1959 at all. The first attempts at mail delivery by rocket dated back to the early 1930s. A German inventor named Friedrich Schmiedl had fired his Experimental Rocket 7 and delivered 102 pieces of mail between the two Austrian towns of Schöckl and St. Radegund. Thereafter, on April 21, 1931, he fired another rocket loaded with mail from Schöckl to Kaite Rinne. In both cases, the deliveries were local, but the excitement the launches produced was great. The legacy of his successful launches is attractive even to this day and the mail delivered in those first flights remains highly sought after by stamp collectors.

In the USA, the first rocket mail was launched on February 23, 1936, from Greenwood Lake, New York, to Hewitt, New Jersey, spanning the frozen waters that separates those two towns. The total distance between them, however, was less than 350 yards and obviously, it was more cost-effective to just row the mail across by boat. Again, the launches caused a lot of excitement. Except as a publicity stunt, practical applications seemed few.

Another great rocket mail experimenter, Stephen Smith, was the Secretary of the Indian Airmail Society. He took up the idea of rocket mail in British colonial India. Starting in 1934 and for the next ten years until 1944, he launched 270 rockets, 80 of which carried mail. The greatest achievement he made was delivering mail by rocket across a river. His “Siver Jubilee” rocket mail postal covers are today hot collectors items.

All of these early successes with rocket-delivered mail, however, had been short range and, despite their success, were never practical. It would take the passage of several more decades of technological development for the world’s first truly long range Missile Mail to take off (pun intended).

The Regulus Cruise Missile

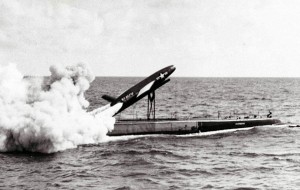

The Regulus cruise missile — more properly, SSM-N-8 “Regulus I” — was the Navy’s key submarine-launched nuclear tipped missile in the early Cold War period. It would later be replaced by the Polaris Missile and then by the Trident, and other systems that followed. By the late 1950s, the US Navy kept at least four nuclear-armed Regulus cruise missiles at sea on board submarines at all times. This was considered necessary to maintain strategic deterrence from the seaborne force.

To achieve the third leg of the nuclear readiness, the US Navy had converted two WWII era fleet submarines, USS Tunny and USS Barbero, into Regulus launch platforms. Two additional submarines, USS Grayback and USS Growler, were then built specifically around the Regulus cruise missile requirement. A fifth submarine, the nuclear-powered USS Halibut, was also brought on line as the world’s first SSBM “Boomer” submarine.

For strategic deterrence, a submarine cruise rotation commenced. USS Tunny and USS Barbero would sail together carrying two Regulus cruise missiles each or, alternatively, any other single submarine drawn from among the other three missile subs of the day would sail carrying four missiles on board. Each Regulus cruise missile could loft a 3,000 pound warhead — a W5 or W27 — over a distance of at least 500 miles. The Regulus I was a subsonic missile, however, and required outside radio signal guidance triangulation similar to LORAN in ships to find its target. Additionally, the submarines would have to surface to fire their missiles, making them vulnerable to attack during launch. These were huge shortcomings, but the idea of a submarine-based nuclear missile force had been born — from there, the US Navy would steadily and dramatically improve its capabilities.

The US Navy Delivers on Missile Mail

By 1959, the Regulus I was obsolete and on the way to the scrapyard. Its shortcomings — very limited range, no inertial navigation system, subsonic, low altitude flight — were simply too great. A newer version, the Regulus II, was in testing, but the Polaris — the world’s first true ICBM — was also soon scheduled to be coming online. For the US Navy, the circumstances were ideal to publicly demonstrate the capabilities of the Regulus I. The US Post Office was also interested in testing the dream of rocket mail.

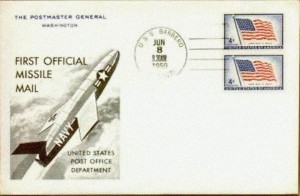

For the first test, the US Navy chose USS Barbero (SS-317) for the task. The Postmaster General, Arthur E. Summerfield, designated the submarine as a temporary post office and 3,000 pieces of mail were collected in Norfolk, Virginia. Prior to sailing, the envelopes were postmarked with the intended date and time of the launch. In turn, these were loaded into a pair of canisters, which took the place that would normally hold the system’s nuclear weapon in the missile’s nose bay. USS Barbero then set sail to its launch station just off the coast of Virginia.

Precisely at the required time, USS Barbero fired a single Regulus I cruise missile down the east coast of the USA to NAS Mayport, in Jacksonville, Florida. In the short time of the missile’s flight, 3,000 pieces of mail were delivered with perfection. The cruise missile was recovered after a controlled landing and the canisters were opened by none other than the Postmaster General himself, who had flown ahead and was waiting in Jacksonville, Florida. The mail was then sorted to prepare it for onward delivery. Weirdly, all of the postal cargo was destined not for recipients in Florida, but for officials in Washington, DC. Thus, after an extremely rapid delivery from Virginia, a state that actually borders with Washington, DC, the mail arrived to Florida which meant that it would have to be carried back to Washington through the regular postal system, which added several days to the journey.

Aftermath

In the end, the world’s first Missile Mail was intended as demonstration of the capabilities of the Regulus I cruise missile more than the US Post Office’s dream of rocket mail. In typical government style, the first Missile Mail demonstrated also the inefficiency, absurdity and bureaucracy of government. Using a rocket to deliver the mail 500 miles in the wrong direction and then laboriously bringing it back by truck and train, past its point of origin and northward beyond for delivery to key officials in Washington, DC, made no sense whatsoever. One of the recipients, however, was the US President, Dwight D. Eisenhower. He opened his letter with a smile, and at the cost of millions of dollars.

At the time, Postmaster General Arthur E. Summerfield stated, “This peacetime employment of a guided missile for the important and practical purpose of carrying mail, is the first known official use of missiles by any Post Office Department of any nation.” Such an encouraging statement masked the accurate point — the one and only example of Missile Mail demonstrated the impracticality of the concept once and for all. The drawbacks included:

- The cost of each rocket far exceeded the postage collected (letters in those days were 4 cents apiece domestic rate, twice that internationally).

- The preparation time for launch was extraordinary — though that could have been reduced over time with practice and better technology.

- Packages or anything that was fragile would not likely survive the accelerations, vibrations at launch and reentry, and the other forces involved in the missile’s flight; though it should be noted that regular envelopes fared well.

- Recovery of the mail packages could be complicated by the missile’s sharp arrival at its destination, which was as could be expected, the crash of the missile into the target at the end of its flight — better termination/landing systems were needed.

Ultimately, however, none of these issues truly doomed Missile Mail.

Just imagine if the dream become a reality. ICBMs would be daily dropping onto major cities worldwide, each carrying just the mail. Would the Soviet Union have welcomed routine ICBM launches from the US into all its major cities? Would missiles from Moscow to New York have been a welcome sight for Americans during the Cold War?

In retrospect, the idea seems ludicrous but, well, this is GOVERNMENT at work after all.