Published on June 11, 2013

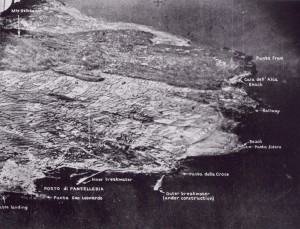

In 1943, at the height of World War II, the Allies embarked on a new offensive plan to pressure the Axis powers of Italy and Germany from the south. The invasion of Sicily was planned for that summer and, from there, it was planned that the next step would be the invasion of Italy’s mainland itself. First, however, a small island south of Sicily, nearly midway between that island and Tunisia, stood as a strategic outpost that had to be taken. Ringed with radar facilities and manned by 12,000 Italian troops, the island of Pantelleria was a veritable fortress. It was well protected too by heavy artillery that pointed seaward. In fact, the Italians had enough firepower to make an amphibious invasion costly.

For Allies, however, as hard as Pantelleria appeared to planners of the amphibious invasion, it also presented an opportunity to test whether air power alone could reduce heavy fortifications, destroy heavy guns and pillboxes and reduce the defenders to the point of surrender without the necessity of a full-on amphibious assault. Thus, beginning in May 1943 and culminating with the scheduled invasion on June 11, 1943 — exactly 70 years ago today in aviation history — the Allies undertook Operation CORKSCREW. The first phases allowed air power to prove once and for all time that it alone could win a major battle. However, while the air victory attained was heartening, it would ultimately become known as the “Pantelleria Curse”. Success, it seems, can lead to unexpected results.

The Aerial Campaign

Pantelleria was a small island of just 42 square miles. It was mountainous and rugged, making it an ideal defensive fortification. The Italians had prepared well, digging in, reinforcing and concealing over 100 major gun emplacements on the mountainous heights and at strategic points across the island. The beaches and harbor were defended by a series of well-positioned pillboxes and defense points. Communications wiring and command centers had been built and covered in concrete too coordinate the defenses against any type of invasion. An airfield was located on the island to help with the defense — the Italians no doubt hoped that they could hold on at Pantelleria as had the British at nearby Malta. After careful strategic consideration, many military experts considered the island to be nearly impregnable at worst or, at best, a serious challenge where huge forces would be required, with victory attained after terrible casualties.

Air power, however, offered the Allies a serious advantage and alternative to a frontal assault with ground troops. German and Italian fighter defenses had been beaten back sufficiently to enable ongoing, intensive bombing raids to commence by May 1943. Medium bombers and heavies, ranging from American four-engined bombers like the B-24 Liberator and two-engined mediums like the B-26 Marauder, made up the bulk of the attack. Fighter-bombers offered tactical air power to swiftly target individual sites. Starting at the beginning of May, the attack commenced — the first target was Marghana Airfield, which was the island’s key defense point.

Marghana Airfield was a huge parallelogram shaped field, allowing take off in almost any direction and making it difficult to bomb to the point that it would be unusable. Two massive hangars, called Nervi and Bartoli, were built at the edges of the field, measuring 340 meters across and these were buried underground to maximize their resilience against bombing. Inside, bombers were parked and fighter planes were hoisted up onto a second level for storage. Massive fuel bunkers were also kept within and buried deeper underground. Despite the extraordinary design of the airfield, it was quickly destroyed along with approximately 80 Italian aircraft on the ground in the first week of the aerial attack (later, it was discovered that two Italian aircraft had survived the onslaught, as had both of the massive underground hangars). Thereafter, the next target was the harbor, which was also reduced with many ships sank.

Targeting the Guns

Thereafter, the Allies began a steady, carefully planned series of attacks that targeted each of the key gun emplacements and bunkers. One by one, day after day, planes launched from the coast of North Africa, including from nearby Tunisia and flew essentially unopposed against the island, dropping their bombs on each fortification. These aerial attacks culminated from June 7 to June 10 with an all-out, final push to bring the island to its knees. On the last day of that four day series of heavy attacks, the remaining Italian commander radioed Rome asking for permission to surrender (other senior Italian officers had departed ten days earlier to escape the air attacks). The following morning, as the amphibious invasion drew near the coast, he received approval and a large white cross was laid out on the center of Marghana Airfield, by which it was hoped that the Allies would see that the island was surrendering.

The signal was initially missed and Allied naval forces moved in close to the shore to open fire with a devastating array of naval gunnery. The Italian response, obviously, was almost nothing. Finally, the amphibious landing craft approached the beaches and, as the men stormed ashore they were met with a stunning array of white flags hoisted from all of the defense points. As Churchill would later write in his memoirs, the only casualty suffered in the landing was that one Allied soldier got bitten by a mule. As for the Italians, casualties were more extensive and approximately 40 percent of the hardened gun emplacements were damaged or seriously degraded — ten were completely destroyed.

Air power had worked and Pantelleria had surrendered — it was an assault witnessed by none other than General Dwight D. Eisenhower himself, the Supreme Allied Commander who was already working on the plans for the invasion of France on D-Day. The success achieved was inspiring and raised expectations of the potential of air power.

The Pantelleria Curse

In the wake of the successful aerial bombing campaign against the Italian forces on Pantelleria, Allied military planners started to make rash assumptions about the future potential of air power to clear the way for the ground troops. Based on Pantelleria, it was suddenly expected that ground forces would occupy much of their time “flitting from one dazed body of enemy troops to another” as zones were pounded into submission by the combined air forces. Sadly, this high expectation would not prove to be the case — at all. Pantelleria was initially celebrated by air power advocates as the proof of a new dawn in warfare. Soon, however, it began to be regarded as the “Pantelleria Curse” as expectations quickly outstripped reality.

Those who were more seasoned and experienced in combat operations knew that Pantelleria was actually something of a special case. Air power had its limits. While air power may have reduced the enemy’s capabilities at Pantelleria very significantly — by as much as half — the surrender only took place once the Italian commander realized that an overwhelming amphibious assault was on the way. The day before, informed through intelligence channels that the assault was imminent, the commander on Pantelleria realized it was a hopeless battled. As a result, he cabled for permission to surrender. The nearby, smaller Italian-held islands also surrendered.

What was missed in the celebration was that fully 47 percent of the Italian forces remained at full combat readiness, a significant force that, had the amphibious landing been seriously opposed, would have turned the island into a massive killing zone. Thus, even if Allied victory was certain, the losses would have been so steep that they may have affected the outcome of the war as planners might well have reconsidered the amphibious landing strategy for France, perhaps depending more on airborne, paratrooper forces instead.

The Limits of Air Power

As later events would demonstrate with blood red clarity, ground forces could dig in and withstand horrific punishment from the air — and survive to defend the beaches afterward. Pantelleria was instrumental in the planning of D-Day, which came just a year later. There, despite thousands of sorties, Germany’s Atlantic Wall not only survived the pounding, but very nearly prevailed in the defense once the invasion began. It would take another nearly 50 years for air power to finally achieve what the earlier advocates had hoped for when, during the First Gulf War in 1991, Saddam Hussein’s massive army suffered 45 days of air attack. At the end of that, the vast majority were ready to surrender to the first ground troops they saw.

One Iraqi unit even surrendered to a drone which, after suffering a mechanical failure, crash-landed in the desert, its camera still operating. The observers at the ground station watched as dozens of Iraqi soldiers came up to the camera and stood around it trying to surrender to the unseen power that was at the controls of the downed machine. It was an apt, even futuristic demonstration of modern aerial warfare.