Published on August 8, 2013

By Thomas Van Hare

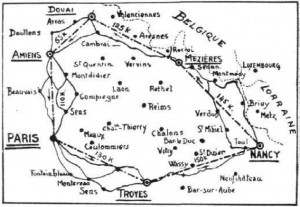

The year 1910 was an auspicious one for aviation. Many new aeroplane designs were in the works and the early models of the 1908 and 1909 period, such as the Antoinette types, were being surpassed by newer, more powerful planes. Aviation meets were steadily expanding and amidst the numerous exhibitions and demonstrations flights, challenges like the Daily Mail’s flights around Britain and rewards for the first to fly across the English Channel attracted great interest both among pilots and among the general public. When the French announced the Circuit de l’Est, many expressed interest. The challenge was a long-distance circular race that sent pilots out from Paris in a counterclockwise route right to the borders of Germany, Luxembourg, and Belgium and back again.

The only problem was that it was an extraordinarily long course — 805 kilometers in all. What would have been impossible a scant 18 months earlier now seemed within reach — and soon 35 pilots signed on for the challenge. It was amazing what just two years had brought — but there was still a lot to learn, as the events of the Circuit de l’Est would soon prove.

Competitions and Plans

Victory in the Circuit de l’Est, which was sponsored by Le Matin, the French news magazine, was to go to the pilot who could complete the full circle from Paris to Troyes, Nancy, Mezieres, Douai, Amiens, and back to Paris. As it seemed unlikely that all would finish — or possibly even any — the rules allowed that the pilot who completed the greatest number of legs along the way (if a tie, then the greatest distance), and, in the event of a tie, to the pilot who achieved the length in the least time. If a winner could complete the entire circuit, the prize would be huge — 100,000 francs. If not, then the sum would be half that.

At Nancy, a series of individual competitions were also scheduled spanning three days from August 9 to 11 — this was not unique and at many stops along the way, competitions were put on at the behest of local authorities who sought to sell tickets to more expansive events at each city. Each competition brought its own prize money. In modern eyes, the tasks were a mix of both the obvious — longest flight, highest flight, etc. — and the surprising — shortest take off, as an example. And mixed in was one competition at Nancy that begged disaster, an award to go to the pilot who could carry the most passengers aloft for the longest flight around the racecourse that doubled as the landing field at Nancy. In other words, the “winner” would be the one who, along with his volunteer passengers, could survive the most overloaded, unsafe take-off, subsequent short flight and landing.

Final Competition Preparations

The flyers and their aircraft gathered together at Issy, near Paris for the start of the race. Weather was promising and the event sold many tickets — with crowds expected at all of the six cities along the route. The Circuit was to take place over many days and, as such, carefully developed plans had been laid on and funded to house the pilots and aeroplanes at each stop along the way. The race wasn’t so much a challenge to see who could fly first all the way around, but rather it was that all of the pilots would do one leg at a time, leaving in a prescribed start order and having their leg times logged carefully.

As the plan would have it, all of the aeroplanes would arrive at each of the cities within a few hours of one another and have a good party in the evenings. That applied to all, except for those who didn’t make it or who were delayed along the route. Bicyclists and medical personnel were also enlisted to ride quickly between cities and lend assistance to downed flyers, a novel solution to a problem that had many organizers concerned — just what to do if a plane crashed and the pilot was in dire need of medical care?

The organizers were complete in every respect, or so they thought. Even the signaling was defined, with messages going out to pilots and mechanics by a three-flag system — white, black, and red pennants would be flown. Black meant that none would fly. White served as a signal that flight would likely begin soon. Red indicated that the flyers were to take off. A black pennant flying under a red meant that mechanics were requested to assist with a downed aeroplane. Lastly, a white pennant under a red one mean that the pilots had all gotten away well.

A Troublesome Beginning

Yet that Sunday, August 7, 1910, instead of the projected 35 pilots, names like Monsieurs Nieuport, Bréguet, Picard, Morane, Leblanc, Sommer, Wallon, and Mamet, among many others (even Latham was to come), by start day, Flight reported that ten were present, of which just eight would manage to take off. What might have been a disaster for the planners, was instead taken in stride — aviation was a new field, after all.

The pilots who did make it for the first leg included Emile Aubrun in his Blériot monoplane, Alfred Leblanc in a Blériot monoplane, Georges Legagneux in a Henri Farman biplane, the German pilot Otto Lindpaintner with his Sommer biplane, Julien Mamet in a Blériot monoplane, and Charles Terres “C.T.” Weymann in another Henri Farman biplane. Hubert Latham came over flying an older Antoinette, while the Peruvian Juan Bielovucic Cavalié (he lived in Paris) arrived on a Voisin. Others had tried to make a showing but, with the rain and mediocre weather the day before (on Saturday), hadn’t made it — for instance, De Baeder failed to show in his Breguet despite setting out (he would come out okay).

Interestingly, almost all of these starters depended on reliable Gnome motors. To serve as escorts, a group of military pilots were tasked with accompanying the men. Lieuts. Cammerman and Aquaviva were present, as well as Moisant — though he had other plans, as everyone would later realize. Finally, Lieut. Lucca came on a Wright machine.

That Sunday morning, when the white pennant went up to signal the start, the order was prescribed by the earlier drawing: The schedule put Latham into the air first, then Aubrun, followed by Bielovucic, Legagneux, Leblanc, and Lindpaintner. At the end, Mamet was last to go — at least that was how it was scheduled. The first leg, straight on to Troyes, would be 135 kilometers.