Published on August 29, 2013

By Thomas Van Hare

The use of drones in military service has a long history. Many remember how German engineers created glide bombs during World War II. These ranged from the larger V-1 “Buzz Bomb” to the smaller, air-launched rockets like the Ruhrstahl X-4, the Fritz X and the Henschel Hs 293. None of these, however, can be properly categorized as “drones”, nor can the unmanned, radio-controlled four-engined bombers of Project Aphrodite (born by the USAAF and USN during WWII). The first such missile was likely the Kettering Bug, but it too is not really a “drone” in the more modern sense.

Today, what most people think of when they hear the term “drone” is a type of unmanned aerial system like the General Atomics Predator. These aircraft perform reconnaissance and attack missions and are remotely piloted — far from being unmanned, they take more men (and women) to fly than a traditional airplane. However, early drones had no such advanced capabilities — rather, they were either free-flying or radio-controlled aircraft with very short ranges. Additionally, they were not used as reconnaissance aircraft, nor did they carry cameras and sensors.

Rather, they served a much lower calling — they were nothing more than flying targets for gunnery practice.

The A-Series Drones

According to most sources, the US Army’s first drones were developed at the beginning of the 1940s. These aircraft included a variation of the Curtiss Fledgling, a plane that was developed as a primary trainer for the US Navy and later adapted by the USAAC as a target drone known as the A-3. There were two previous “A-series” drone models, the Fleetwings A-1 and the Radioplane A-2, both of which served in similar roles starting in 1940.

These aircraft were flown as targets for air-to-air gunnery practice — though that practice soon proved to be far more expensive than employing a “target tug” to tow a banner, which successive members of a flight of pursuit pilots would shoot at in training. This allowed the pilots the opportunity to practice “leading” an aircraft, what is more formally known as the art of deflection shooting.

However, even the “A-series” of drones were not the first. It turns out that the US Army’s first drone predates the Flightwings A-1 by nearly two decades. In fact, it was also the US Army’s first operational glider.

Some make incorrect claims that the first “drone” was an earlier development in Britain, where six prototype unmanned aircraft were built by the Royal Aircraft Factory. While these first flew on June 5, 1917, and were called “AT”, meaning Aerial Target, as strange as it may sound, they were not actually “aerial targets” after all, despite the name. The AT designation was chosen to deliberately mislead the Germans about the aircraft’s true purpose, which was to be loaded with high explosives and flown as a cruise missile. After multiple crashes in testing, the AT design was retired and the RFC declared that there was no future with drones, given what they claimed was their limited military potential.

New and Interesting Goals

In the summer months of 1922, at the US Army’s McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, an aeronautical engineer named Jean A. Roche was hard at work developing a new glider concept for military use. The use of gliders was well-established as a testing training tool among aeronautical engineers. Long before the Wright Brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk, many early gliders had been tested and flown. Chanute, Lilienthal and even the Wright Brothers themselves used gliders to perfect their understanding of aeronautics.

Yet Jean Roche had no interest in developing another glider for flight testing or training. His task was to answer the call by coastal anti-aircraft artillery gunners for a better solution to practice shooting at aerial targets. Clearly, shooting at manned airplanes was not a good idea. Similarly, Jean Roche had heard calls from pilots about wanting a small aircraft that they could actually shoot at for practice — and while practice dogfights with other aircraft (nowadays known as Air Combat Maneuvering, or ACM) were excellent, nothing comes quite close to the actual experience of firing the guns and shooting the “enemy” out of the sky.

Jean Roche’s concept for both was to develop a small, maneuverable, unmanned glider.

The First Army Gliders

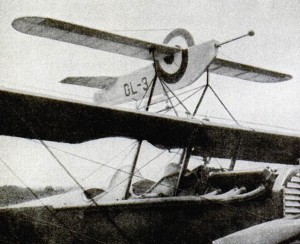

After months of development, in December 1922, Jean Roche’s first target glider, the GL-1, entered testing on behalf of the U.S. Army Coast Artillery. The GL-1 used linen covering a wooden frame mounted on a fuselage that was supported by a tubular metal structure. It was a mid-wing monoplane glider with a 12-foot wingspan. The GL-1 was carried aloft atop the wing of an Army Air Service DH-4 biplane. Once near the target range, it was released from approximately 10,000 feet of altitude. From that height, it would commence a circling descent toward the waiting gunners below. If everything went well and the GL-1 did not suffer any hits, it could fly for approximately 30 minutes, descending at a rough rate of 330 fpm, giving ample time for the gunners to practice.

Soon afterward, Jean Roche developed a larger and improved glider, the GL-2. The GL-2 was a high-winged glider that borrowed its wing from the Curtiss JN-4 Jenny’s upper wing structure. Unlike the GL-1, the GL-2 was manned by an Army pilot who would fly it around, not serving as a live fire target in this case.

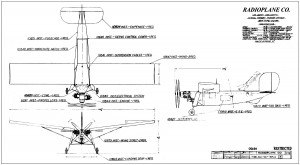

In response to the requests of Army pilots, the GL-3 — also called the G-3 — was developed to serve as a gunnery target for air-to-air practice. Like the GL-1, it was small and carried aloft on top of the wing of the training biplane. The pilot would release the GL-3 and then turn away. Thereafter, after circling back, he would acquire the GL-3 target and repeatedly set up firing passes, practicing his interception procedures, deflection shooting, and air combat maneuvering.

The GL-3 could be set to fly straight, to orbit or to change directions on a programmed pattern, which greatly complicated the practice intercepts. It could even fly a pattern that was called the “falling leaf”, presumably meaning that it drifted left and right in a series of falling chandelle-like turns. As a result, the GL-3, which was quite small, could end up turning at unexpected, if seemingly random points during the planned practice attack passes, complicating the firing solution. Flight tests were carried out with Curtiss XA-4 (s/n 27-244) and the XP-500.

Q-Planes and Beyond

In the wake of WWII, with the advent of more and more sophisticated aerial interception systems, including new-generation air-to-air missiles and radars, the use of drones as aerial targets became commonplace. Many of the retired aircraft were retrieved from the boneyard and converted for “one-way” missions that were flown by radio control. These aircraft were designated with a “Q” to distinguish them from their forebears. As but one more recent example, the famed McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, after retirement, flew its last missions as QF-4 Target Drones for the USAF and US Navy — hundreds were blown out of the sky by American pilots who gained first-hand experience targeting and firing radar and heat-seeking missiles.

As for UAS/UAV aircraft, the term “drone” should never have been used by the media in describing what is arguably a completely different category of aircraft (for reconnaissance and close air support) — but that’s another story.

Dear Historic Wings,

Interesting article. The understand the full story of the British ATs, the best source of data is the Air-Britain book ‘Sitting Ducks and Peeping Toms’ by Mike Draper, (see the Air-Britain website https://www.air-britain.co.uk ).

This book covers the development, construction and use of RPVs by the British from 1917 to 2011(including their use in Iraq and Afghanistan).

Toodle pip!

Nigel Dingley

“…far from being unmanned, they take more men (and women) to fly than a traditional airplane….”

This is a very interesting tidbit. Do you have any numbers to go along with that?

Yes, this is derived from direct discussions in the past year with members and pilots within the UAS/UCAV community. To paraphrase former Secretary of the Air Force, Michael Donley, who summed up the issue perfectly, ‘there is a manpower shortage in the unmanned fleet’.