Published on August 22, 2016

By Thomas Van Hare

Lieutenant Anselme Léon Emile Marchal took off into the gathering evening skies of France. After a brisk turn around his airfield, he headed east into the night. This was one of the most Special Missions of the war so far. His target was Berlin and rather than returning to his base, his route would continue eastward to cross Russian lines and find a safe landing spot there. Extra fuel tanks had been fitted to carry him the distance of nearly 900 miles. It was hoped that the night would hide his passage from German interceptors.

Lt. Anselme Marchal’s story is not of a “Shuttle Mission” taking place in World War II, but rather, one from exactly 100 years ago. He took off into history on June 20, 1916. If his “Special Mission was completed, it would set a new world record for distance. Marchal’s plane was no four-engine bomber, however, but a single-seat, single-engine Nieuport 12 biplane. His chief risk was the poor reliability of his own plane’s little rotary engine. To bolster his odds of making it, he carried a toolbox with spare spark plugs stowed in the cockpit.

As it turned out, Lt. Marchal would desperately need them.

The Special Mission

A year earlier, a German Taube monoplane had overflown Paris and dropped a sack of leaflets. The mission was an early attempt at psychological operations. In its wake, Lt. Marchal, a pre-war pilot of some fame, hatched a plan to respond in kind. After having requested the authority to undertake his special mission, he joined the French squadron, MS 49, based in Corcieux, a small town in the Vosges region of France.

His effort was approved at the highest level and was backed by the French Chief of Staff himself, General Castelnau. The French had learned from the failure of the German attempt at psychological operations. In that case, the Germans had dropped a sack of leaflets from high altitude and it had not opened after it was thrown from the plane. The bag had landed on the streets of Paris with all of the leaflets still inside. Lt. Marchal planned instead to drop his leaflets by emptying the sack completely into the wind stream. Critically, his flight would also demonstrate to the German people that France could bomb Berlin whenever it chose to do so.

In all, 5,000 leaflets were printed for the mission to Berlin. They leaflets carried the following message (the text below is as it was translated from the original German by the editors at Flight, the newsletter of the Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom, which published the text in its July 27, 1916, issue):

We might have bombarded the open town of Berlin and thus killed women and innocent children, but we contented ourselves with throwing the following proclamation: — TO THE PEOPLE OF BERLIN, — Many clear-sighted Germans know to-day that the war was let loose by the military advisers at the Berlin and Vienna Courts. All the official and semi-official lies and perversions cannot do away with the fact that the German Government, with the connivance of the Austrian Government, desiring this war, consciously and with premeditation made it inevitable.

Another set of leaflets were printed with the same message for dropping on the streets of Vienna, Austria.

Flight Planning

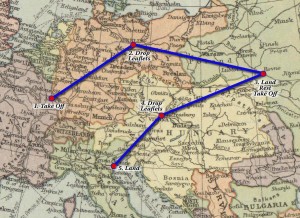

The route of Lt. Marchal’s flight was planned to take off from his airfield at Malzéville, near Nancy. Once aloft, he would fly northeast directly to Berlin, using his compass to navigate by night. Once in the vicinity of Berlin, the lights of the city would guide him in. He would drop his leaflets over the city center, then turn his plane east-southeast to head toward Rovno in Russia (known today as Rivne in Ukraine). This route would take him over Poland and into Russian territories that were occupied by the forces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which itself was allied with Germany in the Great War and locked in trench warfare with the Czarist forces.

By dawn if all went well, Marchal would be deep into Poland. With the rising sun, the risk of interception by air was almost non-existent. The Eastern Front was not as active in the air as the Western, where air battles raged in the skies over the trenches. After reaching Rovno, he would rest, refuel, and then take off to fly to Vienna, Austria. There, he would drop another sack of leaflets over that city before turning toward Italy. He would make his landing on the Po plain.

Aircraft Modifications

To make the flight, Marchal secured a Nieuport 10 and had it extensively modified. Instead of the plane’s usual small fuel tank, which could give the pilot just 2.5 hours of flight time, his specially-built Nieuport 10 carried 354 liters of petrol and 88 liters of oil. The additional fuel tank was mounted behind the pilot in the fuselage — to move the fuel to the front tank (and thereby engine), two Astra fuel pumps were mounted onto the undercarriage rear struts. Thus, when the front tank ran low, Lt. Marchal would start the pumps to refill the front tank from the rear. This was enough to stay aloft for 14 hours. To mount the fuel tank, the Nieuport’s second cockpit (for the observer) was used, making Lt. Marchal’s plane a single-seat version of the plane.

The extra fuel tank required even further modifications to the plane. The plane could not carry the added weight of the fuel needed for the flight. Therefore, a much larger set of biplane wings was fitted, increasing the total wing area from 18 m² to 25 m². As a result, the Nieuport 10’s new take-off weight was increased to about 2,200 pounds (1,000 kilograms). The empty weight had increased from 410 kg to 535 kg. The little plane was powered by a le Rhône 9C rotary engine, boasting all of 80 hp — the engine was chosen because it was the most reliable one produced in France. Even today, many surviving le Rhône rotaries can be spun around freely, giving proof to the engine’s near-clockwork attention in manufacturing.

The Flight

Lt. Anselme Marchal’s flight to Berlin came off perfectly. He took off from Nancy at 9:30 pm. At 3:00 am (Berlin time), he arrived on course in the vicinity of Berlin. The city’s lights were plainly visible in the distance. It was a simple matter to swing the nose of the plane onto a final adjusted course, and head toward the city’s center. For 15 minutes, at an altitude of approximately 500 feet, he circled the city below, picking out landmarks. Then, he opened the sack of leaflets. Without difficulty, he dumped the entire sack into the wind — 5,000 leaflets fluttered down to the city below, spreading widely and catching on roofs, landing on streets and alleys and lightly covering parks and byways. In the morning, the citizens of Berlin would awake to read the message printed on the leaflets — that the city could have been bombed the night before as they slept.

With the sack of leaflets emptied, he turned his plane onto his new course toward Russian lines. A few hours later, the first rays of dawn set the horizon aglow. By then, he was already over occupied Poland. Ominously, his engine began to run rough. At first, it was just a change in the sound. Then, as he continued to press eastward, the engine began to run rough. Soon, it was losing power. He could hold altitude for now, but it was clear that his spark plugs were steadily fouling — or failing.

Finally, with a faltering engine, he selected a field by Chelm, Poland, just southeast of Lublin. He knew that the territory was occupied by the Austrians, who were allied with Germany in the war. He chose a field not only for its suitability for an emergency landing but also for its remoteness. Once down, he would repair the engine as best he could and, if his luck held, he would be off again before the enemy troops could arrive on the scene. He had no doubt that his landing would be observed from miles around, spurring a response, probably with troops arriving by truck to investigate. Every minute on the ground added to the danger.

The Forced Landing

When he put down, he was just 60 miles from the Russian trenches, at the very westernmost part of the Russian and Ukrainian territories (what is now the easternmost edge of Poland). If his engine hadn’t given out and had just run another hour, he could have made it into allied territory.

As it happened, he made a perfect landing in a remote field near Chelm. As soon as the plane was stopped, he quickly climbed out and went to work on the engine. He was well prepared for this — he had spare spark plugs and the wrench needed. As fast as he could, he tried to change the spark plugs — nearly burning his hands on the hot engine. As the minutes ticked by, he changed the first plug, then rotated the engine by pulling on the prop and got to work on the second plug. He could sense the Austrian army closing in — and then, he could hear the sound of their approaching trucks. Moments later, he saw them coming down the road toward the field he was in.

There was nothing left to do but to hurried put in the second spark plug — knowing that so many were still left unchanged — and run around the wing, lean into the cockpit, and flip the magneto switches to on. Then, he ran back around to the nose and gave the prop a mighty heave. The engine didn’t catch. He pulled on it again to spin it. Still nothing. Exasperated, he pulled again. And again. The engine wouldn’t start. Some of the remaining spark plugs, yet unchanged, were too fouled.

With a final heave, he tried his last effort. Then the Austrian soldiers were on him. With nothing left to do, he put his hands up and surrendered. At first, the soldiers couldn’t believe that he had flown all the way from France. The roundels on the wings and fuselage were clearly painted with the Tricoleur, however, and the man before them was definitely French. It would be days later that they would learn that he had dropped leaflets on Berlin.

Prison and Escape

Despite his capture. Lt. Marchal had set a new world record for distance — it was logged and reported variously as either 1,380 km or 1,410 km distance flown. He didn’t feel much like celebrating, however, as he was brought into a prison camp at Salzerbach. Lt. Marchal immediately decided to attempt an escape. For the next six months, he was shunted through a number of prison camps — moving first to Landshut, then Ingolstadt, and finally to Magdeburg — in Scharnhorst prison in Germany. In that time, he attempted three escapes, once only being captured when a fellow escapee fell into the water and nearly drowned. To save him, Marchal was forced to reveal themselves to the German soldiers nearby.

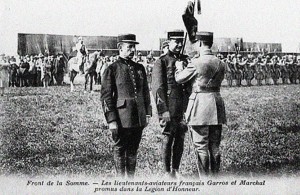

Source: Contemporary Postcard in France

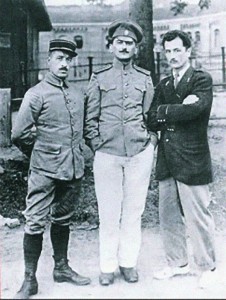

At Scharnhorst camp, he was interned with another famous French aviator, Roland Garros, another pilot well known to Marchal as they were both pioneering pilots together in prewar France. At once, the two began a plot their escape. Though Garros did not speak any German, Marchal was fluent, which they hoped would aid them in their attempt. They developed a plan to simply walk out of the camp at dusk while disguised as German officers. To do this, however, was no easy feat — they would have to develop uniforms that, in the evening light, could pass for the real thing.

Lt. Marchal described how they made the uniforms in his own writing — notably, they chose the ranks of full colonels in hopes that they could use the elevated rank to reduce any potential inquiry or questioning:

In this we washed our two French officers coats, until they ceased to be horizon blue and became campaign grey. The buttons we carved out of wood with penknives, and painted them greenish bronze. Out of our pilots’ overalls we got enough fur to make collars for the coats. One of our friends made us caps. They were a great success. He made the frames out of pieces of cardboard from a box. The tops he covered with blue cloth cut out of a pair of trousers, and then made bands out of a red-flannel belt. This he stole from an old colonel who wore it at night. We hoped the poor old man would not catch a chill. With some nickel he made cockades such as the Germans carried on their caps; and no one at a distance, or in a bad light, could have told them from the real thing. They were “creations.” We cut down some slats of wood into the shape of sabres and blacked them over with shoe-blacking.

Incredibly, the plan worked. On the late evening of February 14, 1918, the two men simply walked out of the prison compound to make their escape. When stopped at the first and second gate by two sentries, Marchal roared about how they had been insulted with catcalls by the French prisoners. He demanded that the soldiers carry a message to the camp commandant that the camp should be brought to order at once. The sentries stood at attention and let them pass, in visible fear of such a superior officer. A third sentry farther on had heard the screaming at the first two and let them pass without a word. Finally, at the fourth and final gate further along, the German guard demanded to see their orders and papers. Though the men had forged papers, they hoped to not have to use them.

Ever fast on his feet, Lt. Marchal again feigned anger. This time, the ruse was that he was insulted at the request. He drew himself up and roared at the top of his lungs that they had had to show the papers three times already! The sentry, recognizing that to get to his final gate, the two men would have already had to walk through three other gates, chose to avoid the fight with a senior officer. He came to attention and waved them through. They walked away from the camp, crossed a bridge, and disappeared into the night.

Running late to catch the train in Magdeburg, they arrived at the station just in time. Garros and Marchal were stopped by a German station guard, but Marchal pointed out that the train was leaving and that they had to get on board at once. The man obligingly helped them climb up and even shut the carriage door for them. From there, they made their way overland to the north. Eventually they crossed the English Channel and made it to England. From there, they were repatriated to France, arriving together as heroes.

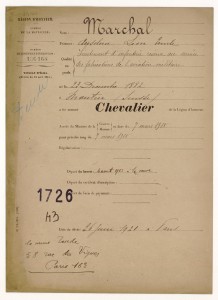

For his extraordinary deeds and escape, Lt. Marchal was made a Chevalier de la Légion du Honneur. He was also promoted to Captain in the French military. With the end of the war, he continued to serve, but not for long — he would die an untimely death in 1921 at just 38 years of age.

One More Thought

The nobility of the French is implied, that they chose not to bomb the city of Berlin and its civilian population. The British, however, highlight the numerous Zeppelin attacks — the world’s first strategic bombing campaign, some say — that targeted the average Londoner in the streets, causing many casualties. This story fits neatly into and promotes a “good war” vs. “bad war” narrative, however, it is overly simplistic and outright false. Both sides were at war and it was a war seemingly without limits.

In Karlsruhe, Germany, there’s a sign that the city has put up that reads: “Während des Ersten Weltkrieges erlebte Karlsruhe zehn Luftangriffe. Der schwerste, am 22. Juni 1916, forderte 120 Tote und 169 Verletzte, darunter zahlreiche Frauen und Kinder, die die Vorstellung eines Zirkus am Festplatz besuchten.”

The translation is: “During the Great War, Karlsruhe experienced ten airstrikes. The heaviest, on June 22, 1916, brought a toll of 120 dead and 169 wounded, including many women and children who were watching a circus performance at the fairgrounds.”

The attack took place mere days after Lt. Marchal’s valiant Special Mission and involved 60 French bombers, taking place on a German religious holiday for the nation’s children. The raid was planned to cause the maximum casualties among the innocent and is considered by some nothing short of a war crime. Today, the people of Karlsruhe still recall the attack as the “Kindermord von Karlsruhe”.

How noble indeed.