Published on June 15, 2012

Resolution of the Incident

Predictably, when the Swedish Government approached the Soviets regarding their responsibility for the two aircraft, i.e., the loss f both the ELINT aircraft and the subsequent search and rescue plane, the Soviets denied any involvement. However, when faced with eye-witness reports of the downing of the PBY Catalina, the Soviets then released an official statement making claim that the Swedish aircraft had fired upon the two MiG-15s, which responded in justified defense by downing the plane (of note PBY Catalinas in US Navy service during WWII were armed with .50 caliber machineguns in the waist ports, lending some credence, even if misplaced, to the Soviet’s false claim — as it happened, the Swedish Catalinas were unarmed).

Despite the public bluster, privately the Soviets engaged in a series of behind the scenes diplomatic exchanges with Prime Minister Erlander. They had made clear through force of arms that there was a limit to just how far they would allow Sweden to go in its shift into the NATO camp. However, despite the blunt nature of their message (delivered in blood, so to speak), the specific operational terms of what the Soviets wanted and what they would allow had yet spelled out with any clarity. Thus, the Erlander and Khruschev governments began the process of working out a new entente for operations in the Baltic Sea. It was a process that would take several years.

Top Secret Equipment at Risk

For the Americans, a key concern was that the Soviets might make efforts to recover the Top Secret AN/APR-9 ELINT system. After discussions with the Americans, Sweden notified the Soviets that any attempt to salvage the plane or its contents would be met with military force. This appeared to have the desired effect and the Soviets did not deploy a recovery/salvage team at the time.

Finally, four years after the shootdown while a summit meeting between Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev and Swedish prime minister Erlander, Khruschev personally confirmed Soviet responsibility for the shootdown of the first aircraft, the ELINT-equipped Tp 79 Hugin. For Sweden, this was a welcome sign — not because they needed confirmation, but rather because it signaled that the Soviets were ready to improve relations by accepting responsibility for what both sides already knew to be indisputable fact. Nonetheless, Erlander still kept the Soviet admission secret from the public and allowed the media focus to remain fixed on the loss of the Catalina. Erlander’s key goal was to not damage Sweden’s public policy of neutrality — not inasmuch as it put Sweden’s security at risk, but rather as an internally-focused policy meant to assuage public concern about the real risks associated with Sweden’s Cold War involvement. It was imperative that Sweden continued to favor a neutral stance, even if everyone in the government and senior military ranks quietly recognized a tilt toward the West.

The matter of the Catalina Affair was quietly resolved and public outcry was tempered through careful public relations. In the years that followed, the Swedish government declined to discuss the matter further. The loss was forgotten by all but the families who struggled with the government’s continuing representation that the Hugin ELINT aircraft had crashed due to a navigation error.

The Truth Comes Out and the Aircraft is Raised

In 1991, two years after the fall of the Soviet Union, independent researchers were able to gain access to the archives of the KGB’s predecessor organization, the MGB, which confirmed that the Soviets had ordered the shootdown of the Tp 79 Hugin. For the families, this triggered the beginning of a campaign to have the deaths of the eight men on the Tp 79 Hugin officially recognized as an operational loss in the Cold War. The men had given their lives in service to Sweden. The continuation of an official line that the flight had been lost due to a navigation error was a travesty, all the more so now that the Soviet reports were public and readily available in the press.

In this context, a retired Swedish Air Force fighter pilot, Anders Jallai, embarked on a crusade to bring the full truth to light and honor the memories of those lost. He enlisted the support of two others, Carl Douglas and Ola Oskarsson, and together with Oskarsson’s company, Marin Mätteknik AB, set out to find, photograph and ultimately raise the ELINT aircraft from the seabed. In doing so, Jallai also hoped to recover the bodies of those lost and bring closure for the families. In the summer of 2003, the team was able to find the aircraft in 126 meters of depth. Later, the wreck of the PBY Catalina was also found on the Baltic seabed, 14 miles farther east. Like the Tp 79 Hugin, the Catalina was found riddled with holes from the MiG-15’s cannon fire.

The remains of the Tp 79 Hugin, along with the bodies of four of the crew members (including the pilot, Alvar Älmeberg), were raised in two operations — one in 2003 and the other in 2004 — with the second operation using a revolutionary new forensic recovery process called FriGeo, also called Freeze Dredging. The Swedish submarine rescue vessel HMS Belos carried a freezing plant and was able to employ the FriGeo system to freeze the top layers of the ocean floor into solid blocks. Then, using slings and cables, the HMS Belos raised the entire aircraft fuselage and seabed together, lifting a total of 200 cubic meters of earth.

The Mystery of What Happened to the AN/APR-9

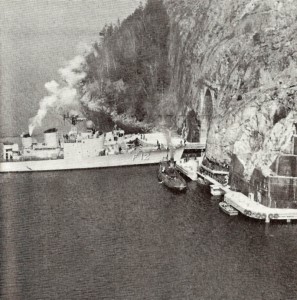

Once recovered, the wreck of the aircraft and surrounding seabed were transported to Muskö Naval Base, a Swedish underground naval facility on the island of Muskö, located just south of Stockholm. The naval base is considered one of Sweden’s most secure, being carved directly into the sides of granite cliffs that jut vertically out of the water. (Today, it is largely closed with only a portion of its 20 kms of tunnels and rooms still active.) Once the recovered aircraft was at the base, a team of security professionals, among others, went to work examining the debris. Recovery specialists began to comb through the seabed to uncover any bodies and other pertinent debris that might aid in the investigation of what happened and how the aircraft was lost.

One of the key items was to recover the AN/APR-9 ELINT equipment from the aircraft. Even after the passage of five decades, the device and its potential contents (if any were still recoverable, which was doubtful) remained classified as secret. The search of the recovered surrounding seabed allowed a complete, in-depth forensic analysis of the crash site and the wreckage itself. Everything was examined closely so as to find and recover the ELINT hardware and other key equipment.

Surprisingly, there was no sign of the American-made AN/APR-9 ELINT radar intercept system. Where had it gone? Had the Soviets undertaken a secret underwater recovery during the 1950s, 1960s or 1970s, perhaps using a submarine and divers to do seabed recovery? It seemed like something out of a James Bond movie, where divers approach the wreck and dismantle the electronics gear on board to take it back to the Soviet Union for secret analysis — but it was all too possible that exactly that had happened.

If this was accomplished by the Soviets, it is likely to have happened no later than in the early to mid-1970s (during that time, the US continued operating the AN/APR-9 ELINT system and it was a key piece of equipment during the Vietnam War). Such a recovery would have been an easy task for the newly deployed Soviet India Class submarine that debuted at that time. The India Class carried to IRM amphibious reconnaissance vehicles that could travel along the seabed on tracks or operate in “swimming mode” with a propeller. In fact, one of the two India Class submarines was deployed with the Northern Fleet from 1976 to 1994. The IRMs were likely to have been pioneered before the submarine was completed.

Whether or not this happened is probably something that will eventually come to light from the Soviet archives. In any case, the circumstantial evidence is compelling — most likely, the Soviets pulled off a covert intelligence coup. As any intelligence professional can attest, truth really is stranger than fiction after all.

Finally, once the examination of the aircraft was completed and all human remains had been recovered and buried, the aircraft was transferred to the Swedish Air Force Museum at Linköping for public display. At Linköping, extensive work had to be undertaken to stabilize the wreckage which was deteriorating now that it was raised. This was a lengthy and costly process. Finally, the Catalina Affair exhibit opened to the public on May 13, 2009. Today, the wreckage stands as mute testimony to the sacrifices of Sweden’s military and intelligence services in the years of the Cold War, defending an unknowing public from the very real threat of war from the Soviet Union.

Aftermath and End Notes

Anders Jallai took action where the Swedish government had been unwilling to resolve the case. His efforts resulted in bringing some level of peace to the families. His work also forced the government’s hand in recognizing the sacrifices of the men who were lost. That he had to proceed as a private citizen with private funding is astonishing, yet it is also testimony to his true character. Without a doubt, Anders Jallai has demonstrated through his actions that he is a man of honor and one who is willing to undertake action where others would not. He took the initiative, despite the steep challenge before him, to reveal the truth and end a decades long lie. Anders Jallai’s greatest achievement in life was not in becoming an elite fighter pilot, but rather in the actions he took after he retired in service of uncovering the truth of events that were long buried.

With the completion of the recovery, the eight men who were killed that day were awarded a gold medal in recognition of their service, a timely gesture even if five decades late. Anders Jallai was also publicly honored by the Swedish government in the same ceremony. Swedish policy had come full circle and no longer would the matter be subject to an officially sanctioned cover up.

Regarding Stig Wennerström, the spy who revealed the nature of the ELINT flights to the Soviet Union, he was convicted of espionage in 1964 and sentenced to 20 years in prison. He served ten years and was released on parole, despite still being seen as a security risk. He was never tried for his role in providing the Soviets the information that brought them to shoot down of the Swedish aircraft. He never spoke of the events, only mentioning the Catalina Affair once during his post-arrest debriefing. Even then, he only mentioned the events informally during a break in his questioning. For its part, the government failed to further debrief him on the matter, choosing instead to leave the issue “buried.” Stig Wennerström died a free man in Stockholm of natural causes in 2006. Unapologetic, he maintained to the end that his spying activities had been meant to “balance” the situation and thereby promote peace, a hard position to justify given the blood that was on his hands from the shootdown.

To date, the remains of the other four crew members lost that fateful day, 60 years ago, have not been found. Notably, there were rumors in the years following the shootdown that a Soviet torpedo boat had picked up a life raft with four Swedish intelligence officers on board. If true, some of the men may have survived the downing of the Tp 97 Hugin after all. What little evidence there is points to the four Swedes being conveyed to Tallinn, the capital of Soviet-occupied Estonia, where they were turned over to the Soviet authorities for intensive debriefings and interrogations. It is quite possible that these four men met the same fate as the imprisoned Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg.

During this era, it has been proven conclusively that the Soviets maintained a number of secret prisoners, including Americans who were captured during the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Furthermore, even as late as the early 1950s, tens of thousands of German prisoners were still held by the Soviets from their battles in WWII. These were men who were captured during the Soviet advance from Stalingrad all the way to Berlin. The vast majority of these prisoners simply disappeared, most dying of starvation, disease or simply being worked to death in the Soviet gulag system.

Notably, in 1980, fully 28 years after the event, one of the widows of the four missing men received a postcard from Leningrad. She was confident that the message was written by her husband, a man she thought long dead. There was no return address and, sadly, no additional contact was made, despite years of waiting. If the postcard was truly from her husband, perhaps after years in prison in the Soviet Union he had finally been released to live out the rest of his life within the Soviet Union, no doubt under the careful observation of the state security apparatus. Perhaps he had cooperated or had been converted by Soviet propaganda — or perhaps he was just temporarily in a situation that allowed him to somehow mail a single postcard. The truth will likely never be uncovered.

In the end, a memorial for the eight crew members lost on Tp 79 Hugin was erected at the Galärvarvet Church in Djurgården, Stockholm. It stands as a solemn reminder of a dark era in Cold War history, a time when Sweden and the Soviet Union quite nearly ended up in a major conflict.

Today’s Link of Interest

Download the U-2 “Utility Flight Handbook”, previously classified SECRET — Copy #7, from March 1, 1959 (18 MB).