Published July 7, 2012

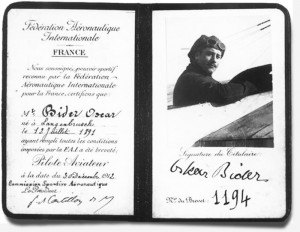

Today, flying across the Alps is little more than a short climb followed by an easy flight looking down on the majesty of the mountains below. Yet back in the early days of aviation, the Alps were a formidable challenge for aircraft. Even a decade after the Wright Brothers first flew, the highest flying airplanes could barely climb above 10,000 feet. A Swiss pilot by the name of Oskar Bider would prove that the Alps were not insurmountable by making a pioneering flight that linked Bern and Milan, directly across what many considered the most challenging section of the mountain range. In doing so, he would cement his position as the “father of Swiss aviation.”

Among the aviation superstars of his day, Oskar Bider was different — he was a soft-spoken, humble man. Initially he was attracted to the open land and freedom that he felt could come with farming life. In June 1911, he traveled to Argentina and worked on a ranch in the province of Santa Fe. Still unsatisfied, just two months later, he read of the death of an aspiring Peruvian pilot named Leo Chavez, a man who had left South America to learn to fly and had attempted to cross the Alps. Chavez’s efforts ended in a crash near Domodossola. Bider determined that as a Swiss citizen, he should learn to fly and help pioneer mountain flying.

Bider Flies the Pyrenees

In November, after just a few short months in Argentina, he returned to Switzerland. He entered flight training at the Bleriot school in Pau, located at the foot of the Pyrenees in southwest France. Over the objections of his family, which considered flying to be not so much a business or pastime as a dangerous venture, Bider soon learned to fly. Once he had soloed, he purchased his own Bleriot and painted Swiss crosses on the wings and tail.

As his first challenge, he would venture internationally to fly from Pau to Madrid, crossing the mountains of the Pyrenees en route. Having trained at Pau, he knew the mountains well and felt that he could surmount them in his Bleriot. This would be Bider’s first great flight and he planned with great care. Among other things, he took a train to Madrid so that he could familiarize himself visually with the landmarks that would aid his navigation. While in Madrid, he prayed at the great cathedrals for success in his daring venture — a distance and route that had never before been attempted.

On January 24, 1913, the weather was ideal for the flight. He would write his uncle about the venture, recounting it this way, “At 6:45 in the morning, by moonlight, I was greeted by the hum of my 70 hp engine. A handshake with my friends and then I am off in my little bird, floating across the starry sky.” It would be approximately 500 km of flying, with a landing in Guadalajara en route before he would arrive safely to Madrid. With this daring flight behind him, he had joined the ranks of the new pioneers of aviation. Soon all of Switzerland was following his flights and he had become the star of that nation’s new interest in aviation.

A Swiss Aviation Hero

In the first week of March of 1913, he returned to Switzerland as the triumphant “aviation hero.” Immediately, he garnered yet more interest from the press by undertaking the first airmail flight in Switzerland, carrying a load of mail from Basel to Liestal. He actively promoted aviation and the potential of flight for the country, doing more than any other to capture the spirit and imagination of the public. This would benefit not just his personal efforts but would help educate the public about aviation and what it could bring to Switzerland in the future. Ever humble and understated, he was the perfect Swiss aviation hero.

Yet the Alps beckoned. His first foray would have him skirt the lower altitudes by completing a flight from Bern to Sion. A good trial flight, he knew that to truly conquer the Alps, he would need to cross the center of the mountain range in an international flight. He chose a route from Bern to Milan, Italy. Like his flight from Pau to Madrid, he planned carefully — a hallmark of his career that many later pilots would emulate. As part of his preparation, he flew his Bleriot to higher altitudes, setting new records, and he pressed the maximum endurance and distances he could fly. He learned through personal experience the hazards of mountain flying, including how winds interacted with mountain ridges, causing dangerous mountain wave and turbulence.

Flying the Alps

Finally, he was ready — an event that happened on this day in aviation history — July 7, 1913. An interim stop for fuel would allow him to carry a minimum load over the highest point of the Alps — with that, he could overfly the highest by just 330 feet — it would prove all that he needed. A contemporary report carried all the details of his greatest triumph:

“[Bider] flew a 230 km route from Bern to Milan with a brief stop in Domodossola, taking off at 4:08 am and landing at 8:42 am, and then onward with 4 1/2 more hours of flying, and, if one includes in the calculation all of the necessary legs of the flight, reaching a total distance of 280 km. He crossed the high Alps exactly at the midpoint between the Jungfrau (4,166 m) and the Mönch (4,105 m). Then he transited the broad Rhone valley and flew east of the Monte Leone to the southern part of the Valais Alps. Never before has any aviator achieved such a feat. Bider has surpassed even himself because he was also the one who just recently crossed the Pyrenees.”

Bider would make the return trip, thus crossing the Alps in both directions.

Bider’s Untimely Death

In 1914, the Great War (World War I) would launch Europe into a bloodbath. Yet it would also bring new advancements in the field of aviation. Throughout the war, Switzerland would retain its neutrality and Bider would serve as a flight instructor, preparing Switzerland’s new air force for the potential of air combat. Soon after the end of the war, in 1919, he would make the mistake of flying after a party with his friends. Drunk, he insisted on showing off his aerobatic talents in his Nieuport 21 biplane (aircraft no. 604). In the middle of his impromptu airshow, he stalled the plane and spun it into the ground. He was instantly killed. Somehow, the most conscientious, carefully planned pilot had made the mistake of trying to fly drunk. It would cost him his life.

Of the crash, Swiss Major General Rihner would later report, “until now [Bider] had never been tempted to fly in a less than sober state, and had always previously been a good example of the correct performance of his duties, yet he was tempted in the early morning of July 7, 1919, to carry out this acrobatic demonstration, which had cost him his life.”

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

The Swiss Air Force was founded on July 31, 1914, under the command of Theodor Real at Bern Beundenfeld, counting Oskar Bider as one of its first nine pilots and instructors. Like many of the other early pilots, out of patriotism, Bider provided the new Swiss Air Force with his own personal Bleriot XI-b, the very one in which he had conquered the Alps. Other aircraft that would be used in that first year included Henri Farman H.F.22, a Morane-Saulnier H, a Grandjean L, an L.V.G. C-III, and L.V.G. C-III-1 and an Aviatik B-II. Bider’s calm, considered approach to flight, coupled with his humble nature helped establish a very valid standard (even modern!) for flight discipline within the new Swiss Air Force. Even his death serves as a lesson for aviators worldwide — that it only takes one mistake of judgment to lose your life in the air. As today’s Swiss Air Force nears its 100th anniversary (which will be celebrated with airshows in July 2014), Oskar Bider’s original Bleriot hangs in the Transportation Museum in Lucerne, Switzerland, alongside many other great aircraft in the history of Swiss aviation.

From the Archives

Jetman Across the Channel — Swiss aviator Yves Rossy is no daredevil, but rather a highly skilled, professional engineer-pilot who does his utmost to minimize risk. His airplane, if you can call it that, however, is little more than a small wing with two tiny jet engines under the wings. His hands and feet are his rudders, he leans to bank, kicks to climb or dive — he is the Jetman.