Published on August 6, 2012

Over the course of a little more than an hour, three B-29 Superfortresses took off from North Field, Tinian, Guam, and turned northward toward Japan. One aircraft, dubbed “Necessary Evil,” carried a small team of scientific observers and a camera crew. The second aircraft, “The Great Artiste,” carried a set of instruments to measure the effects and blast to come. The third and last of the three bombers was named “Enola Gay” after the aircraft commander’s mother. It carried a special payload — a single bomb that was so secret that only three men on the airplane knew of its purpose and capabilities, including Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., who served as the aircraft commander; Major Thomas Ferebee, the bombardier; and a US Navy Captain (a strange addition to a USAF bomber crew) named William S. “Deak” Parsons, who carried the title and role of weaponeer and bomb commander. The augmented crew numbered 12 men in all — and this was to be no typical bombing mission over Japan. This was the year 1945 and the “Enola Gay” carried the “gadget” (the scientist’s name for their experimental atomic bomb) that they had dubbed “Little Boy.” Their target was Hiroshima, Japan.

For Japan, World War II had started in the 1930s with successive invasions and expansions in Asia, even reaching China and Mongolia. The Japanese nation had imperialist goals — to become the dominant power in all of Asia and rule for the benefit of Japan. By 1941, the Japanese were experienced and fielded one of the most powerful militaries on the planet. Their Navy was superior in almost all respects. Their Air Force was top tier, perhaps only equaled by that of Hitler’s Luftwaffe. It seemed like all of Asia was within reach. Yet to achieve such dominance meant that Japan would bump up against two other great powers — the Soviet Union and the United States.

After the Khalkin Gol battles, Japan was able to secure a treaty with the Soviets. The end of their expansion westward had been reached. They would now have to turn their attention to the east and to America, its great strategic rival in the Pacific. The island nation would execute a punishing strike at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and follow up with the bombing and successful invasion of multiple island chains, including the Philippines. Yet the strikes had forced America out of its neutral stance and into a global war which it alone had the power to win. Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany were allies with Mussolini’s Italy and between the three, until America’s entry into the war, it seemed that they intended to carve up the rest of the world into shares between them to rule.

The next three and a half years saw the reversal of all of Japan’s, Italy’s and Germany’s gains. The Soviet Union would rally at Stalingrad and begin the long push to Berlin, culminating in victory in what Stalin called the Great Patriot War. Meanwhile, the US, Canada and England, with surviving forces of the Free French and support from partisans and volunteers from occupied nations like Norway, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia Poland, and many other countries, would press in from the east with landings at Normandy — they too would close in on Berlin, bringing Nazi Germany to an end. In the Pacific, the US, New Zealand, Australia and Britain would undertake a vast island hopping campaign of amphibious landings, spreading Japanese defenders out thinly and reducing their navy and air force to tatters. It would be a hard campaign, yet by 1945, the stage was set for the final act of the war — what most planners and policymakers thought would be the final invasion of Japan.

Even after Italy and Germany were finished, the Japanese would hold on to fight. Debate raged within the top circles of the Japanese Government as some sought an armistice and peace treaty while others believed that victory could be attained if only they fought on. The momentum of the leadership held to a view that an invasion of Japan by the Americans would prove disastrous, allowing Japan to recover and gain peace with reasonable terms, preserving at least some of its independence. The nation readied the nation for the final battle, building up a force of over one thousand aircraft to use as Kamikazes against the coming invasion fleet. Plans were drawn up to train civilians in battle against American soldiers, in hopes of inflicting so many casualties that the American people would lose heart and force an armistice.

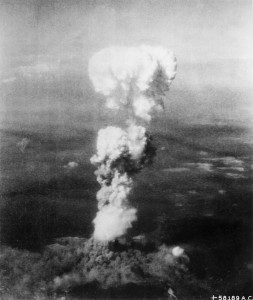

It might have worked, yet this final battle would never come. Instead of a great invasion fleet, just three airplanes would carry a single bomb over Hiroshima. Looking down at the city below through the cross hairs of his Norden Bombsight, bombardier Ferebee would flick the release switch. The single bomb would fall free toward the bend in the river below — from altitude, Hiroshima looked at peace. The bomb was set to air burst over the center of the city, but with prevailing winds, the bomb went slightly astray. Tactically, it could be called a “miss”, except that the explosion and blast radius was so great that it didn’t matter.

On sight of the blast, the bulk of the flight crew on the “Enola Gay” were shocked — over the intercom, multiple voices echoed one phrase — “My God!”

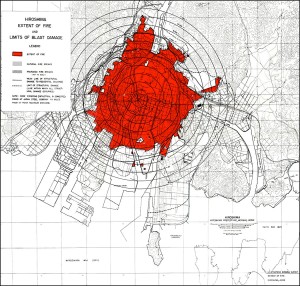

In a single flash, tens of thousands of Japanese civilians were simply vaporized. The shock waves spread out in every direction, flattening buildings and destroying the outskirts of the city. The urban center of Hiroshima was absolutely crushed into rubble, with only a few standing buildings. The radioactive flash from the explosion burned people where they stood. Tens of thousands more would die in the days and weeks afterward. In all, over 90,000 were killed — all by a single bomb named “Little Boy”.

The disaster of the bombing of Hiroshima and subsequent bombing of Nagasaki just three days later would finally bring the nation of Japan to surrender. The Emperor himself would address the people of Japan by radio — for most, it was the first time they had heard his voice. He would ask them to bear the unbearable and accept surrender. The Japanese people would bow down in defeat for the first time in their history. And a new era would begin — the Atomic Age.

One More Bit of Aviation History

The dropping of the atomic bombs “Little Boy” (Hiroshima) and “Fat Man” (Nagasaki) were seminal events in human history. Despite the extraordinary damage these two weapons caused, in modern terms, they are actually miniature bombs. “Little Boy” had a yield of 16 kilotons of TNT, which was sufficient power to kill between 130,000 and 150,000 people. “Fat Man” with its yield of 21 kilotons of TNT, killed 39,000 in its blast and another 25,000 injured from radiation and blast effects. All of this, however, pales in comparison to the destructive potential of the weapons developed since that time — the USA’s B61 weapon, for comparison has a maximum yield of 340 kilotons. The Soviet Union’s largest bomb was the RDS-220 (NATO Code Name: “Tsar Bomba”), which was tested in open atmosphere in 1961. The bomb had a yield of 57,000 kilotons and was air dropped from a Tu-95 Bear Bomber. In one short video, you will come to recognize that nobody, absolutely ever, would have survived a nuclear war.

Message*

Today is the 67th anniversary of the first wartime nuclear attack in history, the bombing of Hiroshima on August 8, 1945. Although it’s not necessarily something to celebrate, the success of the Hiroshima mission was a major factor in bringing World War 2 to an end. Incredibly, a second nuclear attack on Nagasaki would be required before the die-hard fanatics in the Japanese government would finally surrender.

With their surrender the war ended, and the seaborne invasion of Japan was no longer necessary. The Japanese almost always fought to the last man, and although estimates vary, invading the Japanese home islands would probably have cost 50,000 to 150,000 American lives and anywhere from 300,000 to 1,000,000 Japanese lives. These are not just numbers. They represent real people.

During World War 2, it was common to hang a little flag in the front window with one or more blue stars, each star indicating a son or husband serving in the war.

By the war’s end, far too many blue stars had been replaced by gold stars, each indicating the death of a son or husband in the war. If I saw a kid wearing a black armband, I knew the blue star in his front window had changed to gold. My family was lucky… the three stars on the little flag in my front window remained blue.

So, when revisionist historians accuse the United States of nuclear genocide, or whatever they’re using as their current buzz word, think about all those young American men who came home alive, because our nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced the fanatical Japanese leaders to surrender.