Published on September 6, 2012

By Thomas Van Hare

Skimming low over the water north of Hokkaido, Lt. Viktor Belenko had managed to elude the others in his flight that had launched for training. He turned south toward Japan. The other pilots realized — too late — that he had turned out from their practice engagement and dove away. For a few moments, they had considered giving chase, but the distances were too great and their fuel wouldn’t be enough. They knew too that Lt. Belenko wouldn’t get far — as was usual practice, none of their planes had been given enough fuel to make it to Japan, as close as it was.

Yet Lt. Belenko had done the impossible. By careful bookkeeping and overstating his fuel usage on the previous mission he had flown, and then by flying the same airplane on its next flight, Belenko had worked out how to have enough fuel on board to make it to freedom in Japan. His destination was Chitose Air Base — at least he hoped he could make it, whether he had the fuel on board or not would be a close thing.

As he flew south, he expected to hear some reaction from his Soviet superiors, perhaps some trick to get him to turn around. They would call him on the radio with some promise, some message…. And then, as he was racing along just meters above waves, he heard a female voice call him softly through the headsets, “Comrade, you are dangerously low on fuel….”

Prelude to Defection

Lt. Viktor Belenko was one of the selected few who held the high status of being a MiG fighter pilot. He received extra pay, access to special stores for shopping, housing that would be otherwise reserved for the Soviet elites, a car and much more. Yet still, he found life in the Soviet Union to be lacking. The benefits he enjoyed rang hollow. His loyalty was tempered with an educated cynicism that came from his experience as a pilot. Daily ideological lessons were a requirement at which he chafed. He found them to be both repetitive and obvious propaganda. For example, the propaganda films taught repeatedly how bad things were for blacks in America. The camera would pan over scenes of poor neighborhoods, yet Belenko noticed big cars parked in every driveway. He asked himself how bad it could really be in America if even the blacks had Cadillacs. He considered the multi-year waiting list that he was on, hoping to one day assume ownership of a much smaller car that he was entitled to. He found himself questioning — and he later put it succinctly:

“I questioned the Soviet system by using my technological knowledge. I said okay U.S. is so bad how come they send man on the moon and bring him back? (Russians could send men on the moon in only one way.) If U.S. is so bad how come they’re building best fighters in the world? If U.S. is fallen apart how come they have more Nobel Prize winners than progressive communist society? At same time I could not ask anyone those questions. If I had, at that time (in late 1960s), I would have ended up in mental institution. So I made my conclusion that U. S. is not that bad.”

Yet where others lived in quiet cynicism, Viktor Belenko instead played the game very well and applied his intellect to advancement. He was promoted rapidly and soon advanced to flying jet fighters. Then he trained to fly the top Soviet interceptor — the MiG-25, a plane that the West code named as the “Foxbat”. The MiG-25 was the most secret, most advanced Soviet jet interceptor yet built at the time. For Lt. Belenko, it was his ticket to freedom.

The Escape Plan

Lt. Belenko was assigned to the 513th Fighter Regiment, a part of the 11th Air Army within the Soviet Air Defense Force. His fighter regiment was based at an airfield at Chuguyevka Air Base, Primorsky Krai, in the far eastern edge of Siberia. One of the regiment’s missions was to attempt to intercept the SR-71 Blackbirds that would sometimes overfly Vladivostok. Only the MiG-25 could conceivably make a run at a higher flying SR-71 and, if they managed to get into position, possibly even shoot one down. It was a cat-and-mouse game played out large, in which the Americans guessed the essential capabilities of the MiG-25 and planned flight profiles accordingly, while the Soviets tried various types of intercepts and deployments to be lucky enough to wind up in the right position — even once — to take a shot.

For America, getting a MiG-25 in hand was a key intelligence goal — until the USAF could analyze the MiG-25 Foxbat’s capabilities, they would never know exactly what the plane was capable of. For Lt. Belenko, the MiG-25 was therefore the key to his future — he planned on delivering one to the Americans, along with the flight manual, and then assist in training the USAF on how to fly the plane. In return, he hoped for political asylum and a new identity in the West.

The Flight to Freedom

On September 6, 1976 — today in aviation history — Lt. Belenko took off with his flight of MiG-25 for a regular training mission. On such missions, to ensure that no Soviet pilot could defect and make it to Japan (the nearest airport in the Free World), the fuel levels were always carefully recorded and limited. Unbeknownst to the others, however, Lt. Belenko’s aircraft had a bit of extra fuel on board — he had over-reported a fuel burn from the day before and managed to ensure that he would fly the same plane twice in a row. Thus, when the fuel burned was replenished, he judged that he had enough — just enough — to allow him to make it to Japan. It was a gamble, but it was the best he could do

In preparation for the flight, he memorized the headings to fly. He knew the exact distance and timing. He memorized the runway configurations of the Japanese airfield. He worked out exactly when and how he would suddenly break away and dive to the south, leaving the rest of his flight quickly, unaware of his departure for a few seconds. At top speed, even a few seconds would put him out of range of their pursuit — if they could even be decisive enough to realize what had happened. The other MiG-25s in his flight, being the same type as his, could never close the gap once he had gotten out of range. It all worked out on paper — the plan was sound, but would it work?

Just as planned, he had achieved the breakaway and gained the separation from the others in his flight. Nothing stood between him and the Japanese coast. He was already far to the south and, with the throttle far forward, he was running on fumes. Yet he could see the coastline of Japan in the distance.

Suddenly, he was confused by the female voice that came over his headsets. Was this some type of trick? He thought that the controllers were using a woman on the radio to convince him to return. He listened as she began again, “Comrade…” What was this? Then he realized that the voice was exactly the same as before — the same intonation, the same timing, the same exact phrase. It sounded like a recording. He recognized that the voice was the equivalent of a low fuel warning light, but more sophisticated than that. The designers at the Mikoyan-Gurevich Bureau had elected to use a woman’s voice to ensure that the pilot took notice. He smiled — this was the last joke of the Soviet system, a final, if inadvertent trick of circumstance.

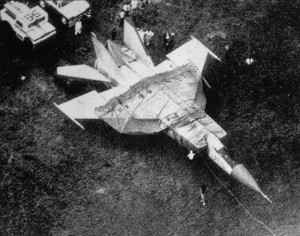

Minutes later, he arrived at the airfield, what he had planned to be at Chitose. He flew a landing approach right onto the departure end of the runway. However, the airfield wasn’t his intended destination after all. Rather than arriving at the military airbase at Chitose, he had come to Hakodate, Japan, a civilian airport. He realized that somehow he had missed the heading or missed seeing the military airfield and overflown it. It did not matter, he would have to land. The runway at Hakodate, however, was too short to handle a high speed landing of a military jet, something that he had researched while planning his flight to freedom. It would have to do.

As he came in, he narrowly missed colliding with a departing commercial airliner — the two planes passed in what would be termed a “near miss”. Then he touched down. Without sufficient runway to stop, he stood on the brakes, hoping to stop before he overran the end. It wasn’t possible. The MiG-25 skidded off into the overrun area and blew a tire. Finally, the plane came to a stop. He was just short of hitting an antenna array, but he had made it. With a sigh of relief, he unbuckled and hit the switch to open the canopy. Later analysis uncovered that on board, he had less just 30 seconds of fuel left in the tanks. The mission was perfect — and it would be his last in a Soviet MiG-25.

When a small group of Japanese officials approached, carrying a white flag in an attempt to peaceably establish the first contact, he handed them a note he had pre-written in English, “Quickly call representative American intelligence service. Airplane camoflauge. Nobody not allowed to approach.” His note didn’t do much good — the Japanese officials took the note and retreated; none of them could speak English. Soon, a translator made an attempt at reading the language of his note and botched the job. The Japanese incorrectly translated his note to read that the plane was wired to explode with a bomb. The unintended result was that it took a little while for things to get sorted out and, critically, the Japanese airport authorities were quick to call the military into action.

Aftermath

Though he would never get to help train the USAF’s pilots regarding how to fly the aircraft (the Japanese were afraid of reprisals from Moscow and so disallowed the Pentagon from taking the aircraft of Japan, much less flying it), Lt. Belenko would be extensively debriefed about the plane and its capabilities. The USAF would take the MiG-25 apart and, coupled with the information that Belenko provided, they would learn that the MiG-25 Foxbat was not as capable or well-engineered as they had earlier believed. They uncovered its limitations, flaws, and quirks. They knew — finally — its true capabilities. While the MiG-25 was an impressive airplane, it was still no match for its American counterparts.

President Ford was in his final year in office at the time — he granted Lt. Belenko political asylum. With the stroke of a pen, Belenko was a free man — at least on paper. Less than a year afterward, the Carter Administration took office. Just five months had passed since Belenko’s asylum had been granted and the new President hoped to improve relations with the Soviets. Incredibly, he ordered the Pentagon to return the plane. Would he also return Lt. Belenko to Soviet hands?

Others in the Pentagon tried to secure the plane for more testing — but to no avail. President Carter felt that the return of the plane was a good gesture. Some wanted to display the MiG-25 at the National Museum of the USAF at WPAFB in Ohio next to other planes that defectors had flown to freedom, such as Kim Suk No’s MiG-15. They too were overruled by the President.

Finally, the US Military complied with the President’s wishes. However, they did it in their own way. The plane was disassembled, every nut and bolt analyzed, and then left in minute pieces, packed up into 30 separate crates, and shipped back to Russia. The unwritten message was clear — Dear Russian Bear, the US has everything we need anyway so here are the pieces to prove it. With best wishes, the Secretary of the Air Force. PS: Nice plane, but nothing we need to keep.

Four years later, through a special bill in the US Congress, Viktor Belenko was granted US Citizenship.

For a time, he was given a new identity to help ensure that the Soviets didn’t dispatch an assassination team to repay him for his disloyalty. However, with the fall of the Soviet Union, Lt. Belenko began to his real name once again. When asked about his motivation to defect in an interview on the twentieth anniversary of his flight to Freedom (in 1996), Viktor Belenko was philosophical, relating to a book he had read while in the Soviet Union. The book was Howard Fast’s Spartacus. He quoted, “You can’t keep a free soul in a cage. You can’t keep eagle in a cage.” To this day, he lives and works in the USA, consulting on the Russian military and the thinking of the Russian leadership.

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

Defections of pilots from behind the Iron Curtain were rare events. Each was celebrated in the West, not only for the front line Soviet hardware that it brought to the USA for analysis but for the freedom it allowed the defecting pilots. From a philosophical perspective, each defector was a signpost on the highway that confirmed the West’s understanding and the popular assumption of the true conditions within the Soviet Union. From the first defector to the last before the flag went down on the Soviet Union, the stories of death-defying escapes from behind the Iron Curtain to freedom remain some of the most inspiring in history.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Who was the first pilot defector to escape from behind the Curtain, in what airplane and on what date?

This was quite an interesting story. I own and have read the book: “MiG Pilot: the Final Escape of Lt. Belenko” by John Barron.

Frank Jarecki was a Polish MiG-17 pilot who defected with his aircraft. He lived near Erie, Pennsylvania, and died a few years ago after spending many years in manufactuting.

In 1978 while assigned to the Aviation Detachment, Berlin Brigade (US Army), the aircraft I was in was intercepted (actually buzzed) by MiG-25s on two separate occasions. I was in a DeHavilland U-6A Beaver for “training” purposes flying within the 20-mile ring around Berlin. On the first buzz one MiG-25 came in slow enough on our right wing for me to actually make the pilots eyes as he flew by. The second occasion occurred two weeks later when two MiG-25s, the lead MiG above to the left of us and the second slightly behind and below to our right went by in full after-burner. Talk about noise, turbulence and adrenalin rush! Though Berlin air traffic control radar had warned us of the ‘fast movers’ at our six we were totally unprepared for the surprise. Not too many Army aviators can say they were buzzed by MiGs.

Where is Belenko exactly now?

The last I heard, he was in the Washington, DC, area doing defense contracting work.