Published on October 9, 2012

Thirteen years before the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, on October 9, 1890, in Brie, France, on the lawn of the Château d’Armainvilliers, Clément Ader was about to make history. At the invitation of the Château’s owner, a wealthy banker named Monsieur Pereire, a runway of 200 meters was cleared on the lawn. As Clément Ader held on, his invention, the bat-winged Éole, raced forward. At the front, a huge four-bladed propeller spun furiously. Behind the prop, running with intense heat and precision, an alcohol-burning lightweight steam engine screamed — this was the key to his invention, an engine light enough and powerful enough to allow Éole to fly. Then, as the speed of the machine picked up, the wings clawed for lift. Suddenly, the Éole began to rise. Incredibly, in a feat that is virtually unquestioned in history, Clément Ader and his Éole flew.

Factually, it is not the Wright Brothers, but rather Clément Ader who achieved the world’s first powered flight in a heavier-than-air aircraft — a point often missed by aviation historians.

A Lifelong Quest

Clément Ader spent years researching and working on his avion or plane, terms he invented to describe his aircraft. In the 1850s, as a teenager, he had worked on model aircraft and had proven many methods of flight on a small scale. Each model flew — or more properly glided — a short distance. While today, children can make simple paper airplanes, in the time of Clément Ader, even such simple designs in paper were far in the future. His models were more substantial, build of wood and fabrics — and each flew, more or less and often less, as he refined his designs.

By the 1870s, Clément Ader was an adult and was working in the administration of the Ponts et Chaussée — the equivalent of a bridge and road works government department, yet from a time before automobiles made their debut. While there, at his own expense, he had tried various tests with small, powered balloons, seeking to achieve safe flight with the ability to exceed the free flight principles of a balloon, in which France had a century of experience since the Montgolfier brothers had first flown. In 1876, he left his government position and dedicated himself to the invention of powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine.

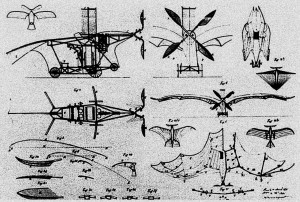

Taking his inspiration first from birds and then, seeking a larger specimen, from bats, Clément Ader sketched his Éole design. The name Éole was drawn from the Greek god, Aeolus, who, in Homer’s Odyssey, gives Odysseus a bag filled with the four winds that the god has captured, allowing him to finally sail home to Ithaca (Odysseus used the gentle and dependable West Wind, naturally). Clément Ader’s design of the Éole was to feature bamboo structured, fabric-covered bat wings that were copied from a pair of live bats he imported from the Indies — these were Megachiroptera (fruit bats) with wingspans of 1.5 meters that he kept in an aviary in his garden. As well, he was deeply influenced by the bird-studies of Louis Pierre Mouillard and his breakthrough book published in 1881 called L’Empire de l’Air. That same book was republished by the Smithsonian in America two years later and would go on to inspire the Wright Brothers and their own flight experiments.

A Lightweight Steam Engine

By 1886, fully four years before his test flight, Clément Ader had already built his Éole, yet knew that he would need a more powerful engine. A dedicated inventor, Clément Ader was no stranger to mechanical and electrical things, so a steam design was not a far reach for his intellect. He had invented treads for vehicles to use in crossing farmlands (much like today’s tank treads or caterpillars) and he had studied engineering and advanced technologies. By 1880, he had improved his knowledge of electrical engineering such that he had improved on Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone and installed his own network of phones in Paris. Unsatisfied with the single ear piece of the telephone system, in 1881, he had invented a stereo listening device that he called the “théâtrophone” — and he then broadcast a stereo opera over a 2 mile telephone line system, thus making this true Renaissance man the father of stereo music.

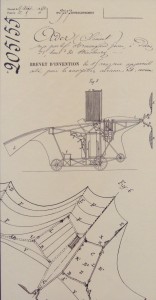

Now with his sights set on producing sufficient power to fly, he undertook studies of steam engines. Railroads were common and steam tractors were appearing in “modern” farms. Steam engines ran in ships and they ran in factories, powering the industrial revolution. It seemed clear that the steam engine was the best option — except that it was far too heavy to have allowed flight. Thus, Clément Ader set out lightening the device. To maximize power, he developed a four cylinder crankcase and block, working out the pressures and minimum metal thicknesses throughout. To further lighten the load and ensure sufficient heat, he adopted alcohol as the preferred fuel, giving the engine intense blue hot flames with which he could rapidly boil water and generate high pressure steam in a small, tight closed loop system. When finished, he had developed an engine that weighed just 60 kg and produced 20 horsepower — it was a marvel of engineering and just what the Éole needed to fly. (Of note, later in 1903, he developed the concept of the V-8 engine design — the first of its kind — further showing his incredible engineering talents.)

The First Flight

On a fine autumn day in 1890, Clément Ader’s Éole sped over the grass at Château d’Armainvilliers. With sufficient speed, the bat wings generated the lift necessary to carry the plane into the air. Only one thing was missing, though Clément Ader had experimented with wing warping for control, his Éole lacked any effective control system. It was simply a matter of racing over the grass, lifting off, flying for a short distance and then reducing power to the steam engine so that the plane would settle back down and roll to a stop. In all, he had just 200 meters of clear grass as his runway in which to prove his experiment — would it be enough?

The Éole accelerated quickly, the four-bladed propeller converting the torque into thrust with reasonable efficiency. Less than half way down the runway, the aircraft lifted off. Gripping the sides, Clément Ader flew a short distance and then cut the heat and power from the engine. Exactly as planned, the Éole settled back onto the grass, landing perfectly on its three bicycle-like main wheels. A fourth, elevated wheel at the back had proven to be unnecessary, though it was there in case the aircraft rotated too much on take off or landing. With some meters of the runway to spare, the Éole rolled to a stop.

In every respect, the Éole’s first flight was successful. Carefully, Clément Ader documented the distance flown — it was exactly 49 meters. As for his maximum height, he estimated with some precision that he had achieved 25 cm (about 8 inches) in altitude. In modern aeronautical engineering terms, he had lifted off and stayed within ground effect, allowing his to fly a short distance despite the heaviness of his aircraft.

Later Developments

Clément Ader’s Éole would not be his last machine. He would go on to build the Avion II, though it is unclear if that ever flew. Funding from the French military and government was cut when he could not show further progress. After that, given the military importance of his innovation, he was sworn to secrecy by the French Army — a strange matter, since they both recognized the military potential of his innovation yet also chose to not fund it!

What made the Éole less important than the Wright Brothers and their first flight at Kitty Hawk? It was simply this — while Clément Ader had managed to lift off, his airplane had no controls and could not truly fly, as the Wright Brothers did, turning left and right, climbing and descending at will. While he had achieved a first, it was a dead end — just as steam-engine-powered airplanes were a dead end from a technical perspective.

Despite Clément Ader’s incredible feat, his greater contribution came only later when he authored a book on the principles of military flight operations, called L’Aviation Militaire. He published in 1909 at a time when aeroplanes were increasingly popular and seemed on the edge of a breakthrough to higher, more reliable and capable flight. His book would go through ten editions and help shape the strategies and tactics of aerial warfare going into the Great War (World War I) of 1914-1918.

Clément Ader’s Final Vision of Aviation’s Future

In the end, Clément Ader would see his principles go to war in defense of France, his home, when it was attacked by the German Army. He would live past the end of the “war to end all wars”, reading the news of the November 1918 Armistice. By then, his French military airplane had truly proven its potential. He passed away while under care in Toulouse in 1925 after having lived a comfortable retirement in Muret, the same town in which he was born in the Haute Garonne region of France.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Among Clément Ader’s greatest visions which he published in his book, L’Aviation Militaire, was the aircraft carrier. He wrote with incredible foresight: “An airplane-carrying vessel is indispensable. These vessels will be constructed on a plan very different from what is currently used. First of all the deck will be cleared of all obstacles. It will be flat, as wide as possible without jeopardizing the nautical lines of the hull, and it will look like a landing field.” Based on his writings, just one year later in November 1910, the US Navy would undertake the development of their own first “modern” aircraft carrier, from which all of the Navy’s aircraft carriers of today have evolved.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What aircraft did Louis Pierre Mouillard create in the 1870s?