Published on October 19, 2012

by Thomas Van Hare

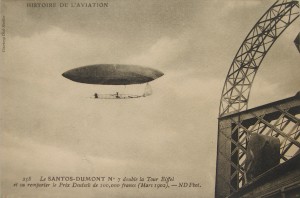

The prize was extraordinary — 50,000 francs — as offered by Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe, a Frenchman known as the “Oil King of Europe” and co-founder of the Aéro-Club de France, along with Ernest Archdeacon and Gustave Eiffel (hence the decision to incorporate the Eiffel Tower in the prize). The requirement was simple, that a pilot of any type of aircraft fly from the chateau at the Parc de Saint-Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back in just 30 minutes total time. The distance, computed in round trip figures, was just 6.8 miles and thus, to achieve that, the pilot would have to fly at no less than an average of 14 mph. Today, this would be an easy achievement, yet when the Deutsch de la Meurthe Prize was announced, the date was April 1900. To accelerate matters, the prize purse expired on October 1, 1903.

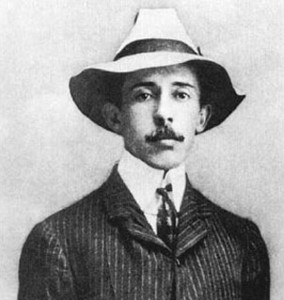

Santos-Dumont and the First Attempts

For Alberto Santo-Dumont, a Brazilian living in Paris who declared himself to be the first “sportsman of the air”, the prize was a dream come true. In the late 1890s, he had mastered balloon flying and, after some experimentation, had developed a steerable, engine-driven dirigible. By the Spring of 1901, he was a well-known fixture in the Parisian social scene. His dirigible was parked at his apartment and at lunchtime, he would ascend into the basket and cruise down the wide Paris boulevards to choose a fashionable cafe for lunch. In all of history, no man has ever mastered urban flying like he did in 1901, literally to the point of using the dirigible for everyday errands and tasks from his fashionable address at No. 9, Rue Washington, Paris, not far from the Arc du Triomphe.

Yet the Deutsch de la Meurthe Prize was something else. By the summer of 1901, Alberto Santos-Dumont had a dirigible that was just fast enough that he could possibly make it. This was his Dirigible Number 5. He could take his time and choose the right day as there were no other competitors yet for the prize, despite the extraordinarily high value offered. Each attempt, however, failed for one reason or another. Each time, he didn’t even make it to the Eiffel Tower. Finally, on August 1, he made a brave attempt, pushing the throttle to the limit.

Yet the stresses on the balloon were too much. His hydrogen-filled Dirigible Number 5 tore open. Rapidly losing hydrogen, he dove toward the ground, attempting to clear a rooftop of the Trocadero Hotel to make the street beyond. He did not make it. The balloon’s structure skidded on the rooftop and the sparks from the impact ignited the balloon above. In a roaring explosion, the balloon was engulfed in flame. Santo-Dumont was trapped underneath in his basket. Somehow, the lines of the basket caught on the rooftop spires and he was left dangling over the street below — luckily, the flames of the burning dirigible burnt out without severing his ropes. With the help of others, he managed to climb to the roof and safety.

Santos-Dumont Launches Dirigible Number 6

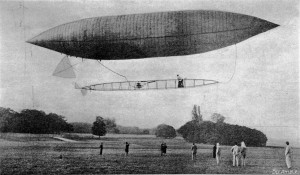

It took another two months before Alberto Santos-Dumont managed to assemble yet another dirigible. This one was more powerful and larger. He called it Dirigible Number 6. It was sleek, shaped like a long sausage with a long latticework hanging underneath in which his basket stood. Like balloons, the baskets of Alberto Santos-Dumont’s dirigibles were all stand-up wicker affairs and this was no different. The basket could only carry one person, despite the large size of the balloon. Further, where the other dirigibles had relied on a long rope for altitude control, in this case, the balloon would fly free at a higher altitude so that he could easily clear the tall buildings of Paris and make a straight line distance to the Eiffel Tower.

Finally, on October 19, 1901, after considerable testing and various trials to prove the handling of the balloon, Santos-Dumont brought Number 6 to the Parc de Saint-Cloud. There, with some fanfare, he departed. The official timing began. Climbing to altitude, he could see the Eiffel Tower clearly. He made a direct flight there and, reaching it without problem, he circled it with precision, as if it were simply a racing pylon. Then he began the flight back. As he neared the Parc de Saint-Cloud, however, the timing was close. He set down and anchored the Dirigible Number 6 to the ground, declaring himself within the time.

The timekeepers, however, were in dispute. There had been some sort of error and soon a debate broke out among them. It lasted several days before finally the decision was made, the Deutsch de la Meurthe Prize was won — his final time was 29 minutes and 30 seconds! By then, the purse had risen to 125,000 francs, which Santos-Dumont graciously accepted. Immediately thereafter, he gave 75,000 francs to the poor of Paris and the rest to his faithful maintenance and construction team as a bonus. The Brazilian Government too offered him another 125,000 francs as their own reward to carrying the name of the Brazilian nation into the record books.

Aftermath and Santos-Dumont’s Later Life

Alberto Santos-Dumont’s victory in winning the Deutsch de la Meurthe Prize was a life changing event. Whereas before, he had been the toast of the Parisian Belle Epoque cafe circuit, now he was a global celebrity. His dirigibles were in demand and his flights garnered regular press attention. He was feted by aristocrats and senior business leaders. He was honored by artists and asked to make appearances internationally. He even came to the United States where he met with President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House.

A year afterward, in 1905, he was pursuing heavier-than-air designs. Soon he had developed his own fixed wing creation as well as a helicopter concept. On October 23, 1906, he finally achieved heavier-than-air flight, although that is another story….

One More Bit of Aviation History

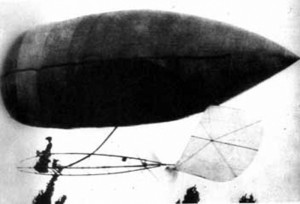

One little known story that relates to Alberto Santos-Dumont regards his “affection” for a Cuban-American woman named Aida de Acosta Root Breckinridge. In all his years flying, Alberto Santos-Dumont never took a single passenger up in his dirigibles of fixed wing aircraft — except for Aida de Acosta. In 1903, spying Santos-Dumont in his Dirigible Number 9, she approached him and asked if she could fly with him. He agreed and gave her three flight lessons. During the the third lesson, she piloted the craft herself, thus becoming the first woman in the world to pilot a powered aircraft in flight.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What does Alberto Santos-Dumont have to do with today’s men’s wristwatches?

Louis Cartier developed the first practical men’s wristwatch to meet a requirement by Santos-Dumont to be able to time his flights.

Cartier still offers the “Santos-Dumont” watch line (as anyone passing through the Geneva Airport will know from the prominent advertisements).

Why was this event important in the history of ballooning?