Published on November 3, 2012

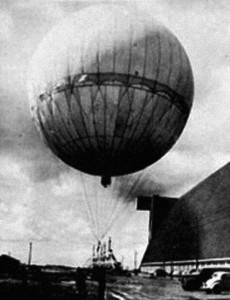

A group of young Japanese women sat on their knees in a gymnasium floor carefully gluing three squares of mulberry leaf paper together with a kon-nyaku paste. Starving, some ate bits of the edible paste and at night, they would smuggle some home to their families. The mulberry leaf paper squares were then glued together into larger sheets that wrapped into a sphere — a hydrogen balloon measuring ten meters across and able to lift 1,000 pounds in an unmanned basket suspended below. Dozens of gyms and warehouse floors were likewise at work across eastern Honshu, Japan’s main island.

Elsewhere, under the direction of the Imperial Japanese Army’s Ninth Army’s Number Nine Research Laboratory, the complex altitude control system was being prepared — if everything worked properly between 6 and8 percent of the balloons would make it to the United States, carrying incendiary and high explosive bombs. These were the Fu-Go, short for Fusen Bakudan, were Japanese final terror weapon against America during World War II. In all, approximately 9,300 balloons were constructed and launched before the campaign ended.

Yet what ended the campaign wasn’t a military action, but rather a victory… by the media?

The Design of the Balloon Bomb

The work was accomplished and organized under the Japanese Army’s Technical Major Teiji Takada. The Fu-Go were based on an idea of Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba, and took advantage of Japan’s discovery of the jet stream. Based on high altitude wind measurements, the Japanese worked out that the jet stream would carry the balloons across the northern Pacific, down through Alaska and Canada and onto the West Coast of the USA. The entire flight would take just three days.

The Fu-Go were far from crude balloons and the altitude control systems were critical to the success of the flight, since the balloons had to fly above 30,000 feet and below 38,000 feet to remain in the jet stream. This was made more complex by the daytime solar heating of the hydrogen gas within the balloon. As the sun shown on it, it would rise. Going too high, it would exit the top of the jet stream and so, based on the altimeter reading, a calculated amount of gas would be released to bring it back into the core of the wind.

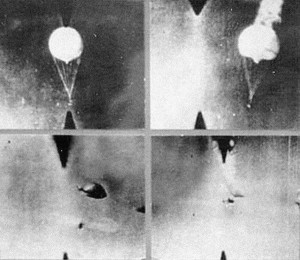

Similarly, at night, with the cooling of the gas, the balloon would descend. For this, the engineers had devised a mechanism that would release small bags of sand from a four spoke wheel, two at a time on opposite sides of the wheel, until the balloon rose high enough to reenter the jet stream. The sand for the ballast bags was packed on the beaches of eastern Honshu. The hydrogen gas was prepared at three factories in Japan. After three days, a timing apparatus would trigger the dropping of the incendiary and high explosive bombs as well as the lighting of a long fuse that would ignite the hydrogen within the balloon.

The Mission

Beginning today in aviation history, on November 3, 1944, the first Fu-Go swarms were released. As each was launched, the Japanese crews would watch briefly as they rose upward until they disappeared into the daytime sky, a tiny spot floating northeast, before they began preparing the next balloon. For the next five months, day after day, weather permitting, the balloon launches were continued.

In the United States, the first balloons went largely unnoticed. Huge swaths of forest stretch across Alaska, Canada, and the Pacific northwest states. Few landed near populated areas. Many disappeared into the Pacific Ocean. Others crashed into the mountains of the Sierra Nevada (some of the bombs may still be out there in the mountains and forests, unstable after all these years and a danger to an unlucky hiker). Some landed or dropped their bombs nearer to populated areas where the explosions were heard.

Over Alaska, American fighter pilots spotted some of the balloons and attempted to shoot them down as they sped along in the jet stream. This was high altitude interception work and the balloons were hard to spot — but a few pilots shot down a handful of balloons. One of the balloons was only partly holed and it crash-landed in an area from where it could be recovered.

The Impact of the Media

As the first media reports of the balloons began to appear, the US Army sprung into action. They begged the press to not report on the events so that any successful bomb drops would not be heard of in Japan. The media complied willingly, hoping to help in the war effort. Likewise, when people found balloons, as was standard policy at the time, they were told what was going on but then sworn to secrecy. One pastor and his wife drove into the country for a picnic with some church school children, aged 11 to 13. While the pastor was parking his car, the wife and the children approached a balloon they spotted — they were killed when it exploded, thus becoming the only casualty of the balloon campaign.

The public was then warned but the balloon campaign was denigrated in the news, part of an Army plan that hoped that the Japanese would be fooled into thinking the campaign was completely ineffective. Meanwhile, Army planners fretted that the balloons would soon be launched to deliver chemical and biological weapons — in fact, the Japanese were well on the way to deploying these deadly weapons, which they considered to be necessary in the final battle with the Allies.

In Japan, their own news media carried stories of American citizens shrieking in panic as dozens of balloon bombs soared overhead. The propaganda had an effect in a time when the Japanese were coming under increasingly heavy bombing attack from the Pacific Air Forces. The first B-29 bombers were already flying missions over southern Japan. Nonetheless, privately, the Japanese military leadership was hoping for better intelligence reports of success, but found none. Finally, they declared the Fu-Go campaign a complete fiasco. In April 1945, it was shut down. By then the B-29 bombers had knocked out two of the three hydrogen factories, which had reduced the launch rates anyway. Yet it wasn’t military action that had killed the Fu-Go campaign, but the media’s decision to hide the results.

Final Words

In the end, over 300 balloon bombs hit the United States. Almost all landed in the unoccupied forests and mountains of the Pacific. Some made it deep into the United States, catching “the perfect wind”. Balloon bombs were found in the expected locations of Alaska and Canada — many others made it to Washington, Oregon, California as well as Idaho, Montana, and Utah. Fewer reached Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota and North Dakota. Two hit Michigan. Some made it to Arizona, Texas, and even into Mexico. In the end, it was an innovative concept, but one that didn’t work well against the sparsely populated western states of the USA.

One More Bit of Aviation History

A far larger balloon campaign was undertaken by England against Germany. Based on a handful of reports from breakaway barrage balloons that had reached Sweden and caused some damage to power lines, Churchill ordered that a campaign of wire dragging balloons be launched when the winds favored flight to Germany (which was most of the time). The balloons would then hope to entangle in high voltage power lines, burning out the line conductors. The plan worked and fires were reported in the news within days of the first series of launches. German fighter pilots would engage and shoot down the balloons (a huge of waste of money given that the cost of shooting down a balloon was far less than even the cost of fuel — each balloon, unlike the Japanese long range Fu-Go, cost just 35 shillings). The program, called Operation Outward, had one large success — a balloon wire shorted out a line, causing a fire at the power generation facility at the Böhlen power station south of Leipzig. The entire station burned to the ground — chalk that up to one less bombing raid needed in the war against Germany.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

For a time, dropping bombs from balloons was outlawed? Why and under what treaty?