Published on November 27, 2012

By August 1944, the US had captured Saipan in the Marianas, one of the last in a series of island invasions that were the hallmark of the Pacific Campaign against the Japanese in World War II. Within days, the US Navy’s famed Seabees were at work building a new airbase that would be called Isley Field. By November 1, the first of the USAAF’snew Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers of the 20th Air Force overflew Tokyo on a reconnaissance mission. Alarmed, the Japanese made attacks against the American bombers on Saipan a high priority. Immediately, bombing raids began — yet these were largely blunted by the fighter cover provided by the combined forces of the USAAF’s P-47 Thunderbolts in daylight operations and P-61 Black Widows at night. Then on November 27, 1944, 68 years ago today in aviation history, the Japanese staged their most daring raid yet. It was a one-way flight of 12 bomb-laden A6M5 Zero fighters. At high noon, the attack began, having achieved complete tactical surprise.

Planning and Approach

With the news reports of the first American bombing attack on Tokyo still echoing through the halls of the Japanese high command, the decision was made to undertake a devastating strike against the B-29 base at Saipan. The mission was assigned to the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 252 Kokutai (252 Air Group). However, the mission was daunting. With the limited range of the A6M5 Zero fighters, there was no way to reach Saipan from the Japanese mainland. Yet Japan still had options. In fact, it retained the small airfield at Iwo Jima — the US invasion of that island was still months in the future. While basing their aircraft on Iwo Jima was impossible due to the near daily attacks by the USAAF’s P-47 Thunderbolts, that site could still refuel any planes that made a quick stop while en route to Saipan.

The problem was that flying from Iwo Jima, to Saipan and then back to Iwo Jima was still beyond the maximum range of the A6M5 Zero. As well, the single seat Zero fighters could not successfully navigate the long distances over water to reach Saipan and stage the attack. The nearby airfield in the Marianas at Pagan was still in Japanese hands and this gave the planes somewhere to land after the raid — though it was clear that the airfield would be nearly instantly attacked once any of the planes landed there. Based on the overwhelming numbers of P-47s that were known to be defending Saipan, the likelihood of survival after bombing the targets, strafing the field and then fighting with the American fighters was very small anyway. Those who volunteered for the mission knew it was a one-way trip.

The 252 Kokutai planned well. A flight of 12 A6M5 Zero fighters would be loaded with bombs and flown to Iwo Jima, scheduled to arrive at nightfall. To assist with navigation, two Nakajima C6N Myrt reconnaissance planes would accompany the planes. Overnight at Iwo Jima, the combined total of 14 planes would refuel and prepare. Before dawn, the planes would depart Iwo Jima. Because the USAAF had fielded radar systems on Saipan so as to warn of any incoming attacks, the planes of 252 Kokutai would have to fly at wave top height, coming in under the radar to achieve complete tactical surprise. If successful, the attack would catch dozens of B-29s on the ground where they were defenseless and easy targets. It was expected that the USAAF would scramble its P-47s and that a low level dogfight would ensue. The pilots were prepared to fight to the death — the hope was that in doing so, they could cripple the B-29s of the XXI Bomber Command and slow the attacks against Japan, at least for a time.

The Mission and Results

The operational plan of the 252 Kokutai came off nearly perfectly. In a testimony to the low altitudes that the Japanese pilots flew to avoid radar detection, during the final hour on approach to Saipan, one of the Zero fighters clipped the top of a wave with its prop. Suffering damage that made it impossible to proceed to the target, the pilot had to abort, drop his bomb into the water and divert to Pagan. There, he hoped to land. The remaining 11 A6M5 Zero fighters continued on — at noon they arrived at Saipan as the two Nakajima C6N Myrt reconnaissance planes turned back to Iwo Jima — both returned safely.

Not all luck was on the Japanese side that day, however. In the hours before the attack, by coincidence the XXI Bomber Command had launched its second full scale B-29 bombing mission against the Japanese mainland. Thus, most of the B-29s were long gone when the Zero fighters came over the horizon and began their attack. For the 252 Kokutai, their only targets were those planes that had not been mission ready and were undergoing maintenance. Nonetheless, the Japanese achieved complete tactical surprise. Initially without interference, they pulled up and rolled over into their planned bombing attacks. With air raid sirens howling and AAA crews opening fire, the 11 Zeroes made a devastating attack on the remaining B-29s. Five of the Superfortresses were hit, of which three were soon destroyed, ablaze and unrecoverable.

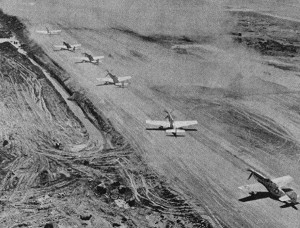

As the Japanese Zeroes came around to begin their strafing runs against the facilities and other aircraft parked on the field, the USAAF’s P-47 Thunderbolts scrambled to take off. Other P-47s that were flying overhead as fighter cover dove down on the Japanese in hopes of disrupting the attack. Soon the air above Isley Field was a swirling mass of fighters in close combat. One by one, however, the Japanese planes were shot down, overwhelmed by the heavy and powerful American fighter planes or hit by AAA fire. Concurrently, at Pagan, the lone damaged Zero that had hit the waves was spotted by another flight of P-47s as it made a dash toward the runway. They pushed over and closed rapidly, shooting it down well short of the runway.

A Final Act of Bravery

Out of ammunition, the final Japanese pilot recognized the impossibility of continuing the fight in the air. His last weapon was his pistol — and he intended to use it. Bravely, he dodged through the pursuing P-47s and set down right on Isley Airfield. Shutting down his engine, he brought the plane to a stop, threw back the canopy and leapt from the cockpit. Once on the ground, he drew his pistol and began firing at American troops along the runway perimeter, including those manning the AAA sites. The lone pilot’s bravery was witnessed by Brig. Gen. Haywood Hansell himself, the commanding officer of the XXI Bomber Command who could just stand in awe of the man’s bravery as American infantry finally shot him with their rifles.

Amidst the chaos of the air battle, the P-47 Thunderbolts had claimed four of the 11 Zeroes, while the AAA gunners had managed to shoot down six. The eleventh and last, as noted, had landed intact on Isley Field. Yet the AAA gunners had also managed to down one of the P-47 Thunderbolts, a friendly fire incident that was later deemed “inexcusable” in the official report that followed the action.

Aftermath

Recognizing the potential damage that the Japanese surprise attack could have done had the bombers not been scheduled for a mission that day, the 20th Air Force brought in more fighter cover. Bombing attacks and suppression raids on surrounding enemy airfields were increased so as to try to eliminate the possibility of another surprise attack. To ensure that the low level approach below the radar could not be repeated, the US Navy was ordered to deploy two destroyers 100 miles north of Saipan as a radar picket line. If another raid came in, at least 25 minutes of advance warning would allow the USAAF to scramble its P-47s (and later P-51s) and intercept the Japanese planes well over the sea. As well, two B-24 Liberators fitted with airborne radar systems were dispatched to Saipan to provide an airborne early warning radar system (this was the first use of airborne radar control aircraft in USAAF history).

Despite all of this, some of the following Japanese shuttle raids through Iwo Jima slipped through, going around the destroyers and avoiding detection. Finally, on December 7, 1944, on the anniversary of the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese penetrated with sufficient air power and attacked with a combined force of high altitude and low altitude aircraft in a simultaneous assault. This time, the XXI Bomber Commands entire line of B-29 bombers were caught on the ground, lined up in along the sides of the taxiways of Isley Field. Combined, the Japanese attack destroyed three of the B-29 Superfortresses and damaged another 23 of the heavy bombers — the greatest success yet achieved.

One More Bit of Aviation History

While the raids on Saipan slowed the American strategic bombing campaign against Japan, it did not stop it. The months of 1945 proved the most devastating time in Japan’s history. One by one, the Marianas were taken and additional airfields brought into service. Soon the island chain was like a massive bomber base with dozens of runways active at once. What followed included the devastating Tokyo fire bombings and the mass scale strategic attacks against Japanese industry and cities throughout the mainland. Iwo Jima fell to the US Marine Corps — truly one of the greatest victory in USMC history — and soon the American P-51s were based far enough north to provide escort cover for the bombers as they flew over Japan. With Japanese air power dramatically weakened, the island was left virtually defenseless. Finally, in August 1945, the USAAF was able to launch its two nuclear weapon attacks against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the war — the planes launched from North Field in the Marianas.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

How many airfields did the USAAF have in the Marianas and, combined, how many runways were in use by the end of the war?

My father was General Hansell’s driver. I would like to get a copy of the newsreel of the daylight Japanese bombing raid. It is supposed to show my father drive Gen. Hansell in a jeep during the bombing. Do you know how I might obtain a copy?

Thank you.

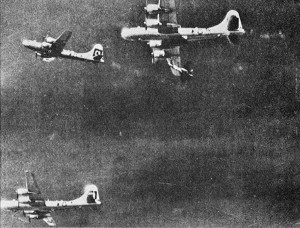

The photo on the Ki-45 passing under the B-29 was taken duing a raid on May 5, 1945 on Tachiarai airbase. The AC was piloted by Lt Marvin Watkins. My UNcle Bill , Lt William Fredericks, was the the co-pilot. This photo also appeared in Life Magazine sometime in summer 1945. Moments after this photo was taken #4 engine caught fire and the crew bailed out. Of the nine crew who remained, Capt. Watkins was sent to Tokyo and tortured, but survived the War. His eight fellow surviving crew members, however, died from vivisection experiments performed at the Department of Anatomy, Kyushu Imperial University, Fukuoka, Japan. Of the 12 original B-29s in the 6th Bomb Squadron, only three survived. The crew arrived at North Field in March of 1945, and flew between 8 and 10 missions. Several mission they suffered battle damage or engine trouble and at least once had to make an emergency landing on Iowa Jima for repairs.