Published on December 21, 2012

By Thomas Van Hare

Hélène Dutrieu was a professional bicycle racer from Belgium. Known as “La Flèche Humaine” (“The Human Arrow”), she was famous throughout Europe for her speed and stamina. She won the women’s speed track world championship in both 1897 and 1898 and then also the Grand Prix d’Europe in 1898. By the early part of the 20th Century, she had given up on bicycle racing to become a stunt cyclist. One of her stunts was to ride fast enough to hold to a track in a vertical loop, which she displayed in a show in Marseille. She moved on to motorcycle and automobile stunts and became a race car driver, racing professionally from 1904 to 1907 for the French company Clément-Bayard de Levallois. Finally, she set her sights on becoming a pilot.

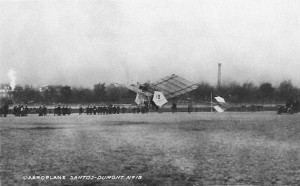

Who better than Hélène Dutrieu to become the first pilot of the Santos-Dumont No.19 Demoiselle monoplane? At least that is what her racing sponsor, the Clément-Bayard Company, thought when they considered who should represent their new aeroplane. Likewise, Hélène Dutrieu wanted to fly. She had witnessed the Wright’s first flying expositions in France. The choice of a woman as a pilot was apt because the name of the plane, Demoiselle, is the French word for a young lady. Thus, it seemed the natural choice of a woman daredevil, race car driver to take into the air.

Among the potential women pilots who might represent the company, Hélène Dutrieu had one advantage over all others — she was a petite woman. She weighed less than any of the others. For the under-powered aeroplanes of the time, this was a critical consideration. In 1908, Hélène Dutrieu began her long and beautiful relationship with the world of flight and aeroplanes — one that was fraught with life-threatening risks. Many pilots in those early years crashed and were killed.

WATCH THE VIDEO!

First Flight and First Crash

In 1908, times were very different than they are today. Women were not deemed to have the right to vote, nor considered to be suitable for most types of work. They were considered “the weaker sex”. As such, they were relegated to the role of caregivers at home. For a woman to fly was dramatic. The Clément-Bayard Company thought that if a woman could fly their Demoiselle, which sported a heavy 50 hp engine, then men would come to understand that flight was not something out of reach and too difficult. After all, the company’s thinking went, if in any entirely sexist manner, if a woman could fly, then so could anyone. Given the risks and potential death of Dutrieu, however, the Company recruited a second pilot, Mdlle. Aboukaia — just in case, as the saying goes. The two women were soon learning the technical details of the Demoiselle.

Hélène Dutrieu had the highest hopes for her first flight. However, it proved to be a disaster. She crashed right at the start. Luckily, she walked away from the wreckage unhurt. To learn to fly, she decided to apply to study under Roger Sommer. Thus, after being accepted, she went to school at the Henry Farman Aviation School. Both of the instructors there were former cyclists like her. A fast learner once she had proper guidance, she was soon in the air. In 1910, she made a notable first, taking her mechanic up in an aeroplane and thus becoming the first woman pilot to carry a passenger on board an aeroplane.

Flying Without a Corset!

Indeed, “la Flèche Humaine” had earned herself a new nickname and became known as “the Lady Hawk” (“la femme épervier”). Though she carried a youthful appearance, she was actually 31 years old when she first took to the skies. This reflected her years of cycling and stunt riding, which had kept her in excellent shape. Her youthful look only furthered the impression of the ease with which men (and women) could fly.

Though it wasn’t instantly apparent from her thin waist and appearance, the press somehow discovered that Hélène Dutrieu was flying without wearing a corset. Aghast, they published the revelation — to the public, even if a woman could fly, there was no reason for her to abandon herself to immodesty! News reports of the scandal rocked the public, though it also somehow made her more famous yet. Apparently, there were those who thought it was interesting that she was apparently so “wanton”.

Hélène Dutrieu shrugged it off. She persevered and continued to fly, even as officials gathered for meetings in Paris to discuss whether she should be allowed to fly without proper feminine corsets.

The formal debate and rulings about her corset-free flying habits were cut short when she suffered yet another crash. As Flight reported in its January 29, 1910, issue:

“On the 21st inst. (January), while Mdlle. Hélène Dutrieux was practising on her Santos-Dumont machine at Issy, she had a somewhat exciting experience, which fortunately ended without injury to herself. The ground was very muddy and heavy, and in her endeavours to get the machine to rise, Mdlle. Dutrieux pushed the elevating-lever right over, with the result that the machine shot up very suddenly to a height of ten metres. It flew along for a few minutes, and then as suddenly fell forward, and after striking the earth remained standing perpendicularly. Much to the relief of the terror-stricken onlookers, Mdlle. crawled out from her seat quite unhurt by the fall.”

Hélène Dutrieu chose to continue her stunt and exhibition work, using aeroplanes as a continuation of her former racing shows. She decided also to enter into competitions as a way to advance her popularity. This meant that finally she had to get certified as a pilot. On November 25, 1910, she applied for and received her flying license — Aéro-Club de Belgique License #27, becoming only the fourth woman in history to be a certificated pilot and the first from Belgium.

The Coupe Femina

The publisher of one of France’s most popular women’s magazines, Femina, was a man named Pierre Lafitte. To express his interest in aviation — and for the marketing impact — he announced in 1910 a prize of 2,000 francs to the woman who each year set the record for the longest flight, based on distance flown and time aloft, in an aeroplane. The competition was to be less of a head-to-head affair, as other endurance races usually were, and instead relied on validated reports from officials who could attest to the times aloft achieved at any time during the year. Thus, many of the new aviatrices submitted their flights as they flew them, from wherever they were flying, throughout the entire year. The competition was hard fought. Many would make claim of an unbeaten, new longer distance, only to be surpassed by another a month later, and so forth. As news of each record-breaking flight came in, the few women pilots that were active at the time would take to the skies once again.

The prize money was attractive, but even more so was the glory and public recognition that would come to the aviatrice who won the competition. For Hélène Dutrieu, the competition was the ideal way to gain the fame she needed to start her new career flying exhibition flights to paying audiences. As reports of other flights came in, one after another, and the potential victor shifted from one competitor to another, Dutrieu decided to push the limits to an incredibly difficult distance. She not only succeeded when she flew, but handily won. Her flight began at Étampes and she flew 167 kilometers in 2.6 hours in a Farman Biplane. With just ten days left to the end of the year, the rest of the competitors had to throw in the towel and recognize that they had been bested, fair and square.

Her record was set on this date in aviation history in 1910. The prize was announced just ten days later on December 31, 1910.

Her prize winning flight achieved what she wanted. Buoyed by the recognition that it provided, for the next three years she flew on the airshow circuit around Europe. Thereafter, she defended her Coupe Femina victory with yet another in 1911. Finally, she retired from flying in late 1913, having also been awarded the Légion d’honneur for her extraordinary achievements.

In practice and in spirit, she wrote her name into the history of women aviation pioneers for all time to come. It is from women like Hélène Dutrieu that the 99’s and others would draw their inspiration.

She proved that women could fly even without a corset!

One More Bit of Aviation History

The closest finisher to Hélène Dutrieu’s 1910 record in the Coupe Femina was Marie Marvingt who flew 42 km in 53 minutes with a flight that started at Mourmelon, France. Interestingly, both Hélène Dutrieu and Marie Marvingt became ambulance drivers during World War I. Marie Marvingt, however, also flew in combat. In fact, she may have been the first woman to fly in combat in history. She performed the first bombing mission flown by a woman in 1915 when she attacked the city of Metz. She was later awarded the Croix de Guerre for her exploits in the air serving France against Germany.

Marie Marvingt’s crowning achievement, however, was not in war, but in peace. She created the world’s first air ambulance service.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Marie Marvingt was the first woman to fly a bomber in combat. Who was the first woman to fly a fighter plane in combat?

Princess Eugenie M. Shakhovskaya was Russia’s first woman military pilot. Served with the 1st Field Air Squadron since late-1914. Unknown if she actually flew any combat missions, and she was ultimately charged with treason and attempting to flee to enemy lines. Sentenced to death by firing squad, sentence commuted to life imprisonment by the Tsar, freed during the Revolution, became chief executioner for Gen. Tchecka and drug addict, shot one of her assistants in a narcotic delerium and was herself shot.

I believe that there is an error in this article, as I do not think that Shakhovskaya was ever a military pilot. Please check.

Hi, for an upcoming publication I’m looking for additional info and pictures on Helene Dutrieux. All info is welcome. Kind regards, John