Published on January 31, 2013

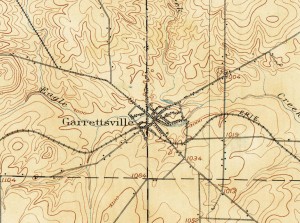

On January 31, 1928 — today in aviation history — the US Postmaster, Mr. Harry S. New, issued a Federal Government order to all US Mail contractors to climb to higher altitudes before flying over the small town of Garrettsville, Ohio. His reasoning was simple — based on a complaint received in the mail, he intended to reduce the effect of noise on a commercial business known as the Cackle Corner Poultry Farm. From this single order, however, the US Government and its judicial system were brought into a pitched battled of claims and counter-claims that would ultimately pit landowners against aviation interests. At stake was a singularly devastating question — did landowners have ownership rights to the airspace above their properties and, if so, how high? Indeed, what started at Cackle Corner would soon expand to become one commercial aviation’s greatest challenges in history.

The Cackle Corner Incident

It all began on a poultry farm. With the award of a new air mail contract, a new commercial air carrier called National Air Transport Co. (NAT) began flying twice daily overhead on their New York to Chicago route. Most of the time, they flew at fairly high altitudes, but sometimes, such as when low clouds forced the air mail planes down low to scud run under the clouds, they would pass low over the Cackle Corner Poultry Farm. The farmer observed that his chickens were noticeably agitated whenever the flights passed overhead. From there, it didn’t take long for him to log a decrease in overall egg production. As summed up in TIME Magazine in early 1928, the problem had reached a critical stage:

Twenty-five hundred hens of the Cackle Corner Poultry Farm at Garrettsville, Ohio, cocked a frightened eye, ran wildly about the barnyard, bumped into, trampled on, injured one another. Next day they did not lay so many eggs. Reason: hens have ears (not visible to the casual observer) and they heard the ear-splitting roar of a low-flying airplane carrying U. S. mail. This roar came twice daily and began to interfere with the profits of the proprietor of the Cackle Corner Poultry Farm. So he wrote a protest last week to U. S. Postmaster General Harry S. New….

The problem was detailed in clear terms in the poultry farmer’s letter, which read:

“I am a poultry raiser keeping about 2,500 Longhorn hens. About once in two or three weeks an airplane, sometimes it is a U.S. mail plane, flies over my place so low that the hens become so frightened that they pile up, thus injuring each other and my egg yield drops one or two hundred eggs per day, and by the time I get them back to normal along comes another low flying machine and sends the egg yield down again…. The loss to me is so great that I fear it may put me out of business. I wondered if the planes could not be requested to fly higher.”

Not unexpectedly, the Postmaster, Mr. New, took swift and effective action to head off what he could see might become a serious problem. His action was also drawn from his knowledge of the increasingly shrill public voice regarding the unexpectedly disruptive aspects of commercial aviation.

Taking Action

The problems at Cackle Corner, clearly, could expand nationwide if they weren’t nipped in the bud. Hence, unknowing of the long term effect of his actions, Postmaster Harry New set in a motion the exact opposite of his original intent — rather than “nipping the problem in the bud”, he had inadvertently launched a serious (though perhaps timely) property rights battle. He ordered National Air Transport Co. to fly higher whenever it passed directly over Cackle Corner. Yet in less than a year, this simple order would become the basis for airspace property right claims nationwide.

Whereas the new business of aviation had once been welcomed as a novelty — man can fly, what a sight to behold! — that changed once commercial contracts routinized and regularized. By 1929, the commercialization of aviation had evolved into a daily, weekly and even monthly nuisance of low flying airplanes with noisy piston engines.

An Expanding Problem

Vacationers who stayed in cottages on Rhode Island were soon complaining about the many airplanes that flew down the beach en route to Boston. In Nebraska, a fox farmer complained that low flying airplanes were causing his foxes to miscarry, which was seriously affecting his furrier business. A wealthy estate owner was upset that an adjacent property had become an airport and that planes flew overhead daily, disturbing what was previously an idyllic, quiet life in the country.

Long Island’s Roosevelt Field, one of the major airports serving New York, realized too late that it bordered an elite country club. The wealthy golfers there complained bitterly about the aircraft noise that was disturbing their sport. Finding no answer in the courts or through letters to the US Congress, the country club built a 125 foot high wall on the edge of their property that bordered the departure end of the airfield. The result was that aircraft had to take off in the opposite direction, even if it meant doing so with a tailwind.

Just two years after the Cackle Corner Poultry Farm incident, aircraft litigation regarding property owner’s claims to airspace rights had spread nationwide. Each state was soon setting new precedents and rulings on the matter. Two main avenues of interpretation emerged, one being that the landowner had rights to some airspace, but not above “all the way to the heavens”; and the other being that if the aircraft were not a significant nuisance then they should have the right to free passage.

However, new and more powerful airplanes meant more noise from every plane as it flew overhead. The effect was multiplied by the expansion of air mail contracts, passenger services and cargo flights. This meant more and more flights. Ominously, with Federal Government inaction, many landowners who were bothered by the noise and intrusion of airplanes began to claim the airspace above their homes, farms, ranches and businesses. By legal precedent, they were able to establish that overflights could be construed as “aerial trespassing”. In many states, illegal trespassers could be shot and many landowners were armed. The issue had come to a head — if such claims were allowed to gain a foothold in case law, the potential of commercial aviation would be permanently hobbled.

Solutions and Compromises

Over time, the matter was settled through the creation of new laws and the imposition of court rulings, which were then extended as nationwide precedent. Even so, the new airspace rights laws came about in a hodgepodge, often conflicting manner. Some properties were granted more rights to higher altitudes, but others were not. Some judges claimed that the matter had to be decided property by property, not through some blanket application of universal law. Many landowners saw the benefits to air travel, but other did not. Arguments fragmented and tempers flared. In some cases, judges ordered police to visit properties and subjectively verify the claims of the nuisance factor involved, which lead to unequal rulings and further arguments.

Ultimately two things saved the day. First, the commercial aviation industry was far better organized than the multitudes of bickering private landowners across the nation. And second, from Washington’s perspective, the airspace above privately held lands had security implications for the nation’s defense. Ultimately, the matter was resolved with an understanding that flights should be avoided within 500 feet of any person or object (such as a building) on the ground. Access to public airports could not be blocked by private landowners, nor would overflights constitute “aerial trespassing”, as long as they were done at sufficient altitude.

It was a reasonable compromise — at least until the advent of large passenger jets and supersonic flights with their sonic booms. That would come later, however, in the 1950s and 1960s — and give birth to an entirely new debate, that of noise abatement.

But that’s another story.