Published on January 9, 2013

Today in aviation history marks the birthday of Richard Halliburton, adventurer, aviator, author, grand lecturer and world traveler. Born in 1900, Halliburton was a graduate of Princeton. As many who attended the finer institutions of education in the day, Halliburton set out on a “Grand Tour”, yet where others would travel by boat to Europe and visit Paris, Rome, and all of the other wonderful cities of Old World, Halliburton took a different path, taking to a ship as an ordinary seaman. After his return, he was transformed forever — he dreamed of nothing but adventure and travel. His goals became to see the world and to write and lecture about of the experience.

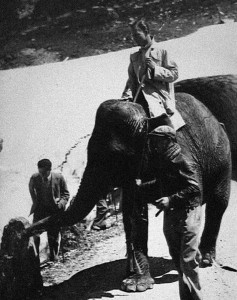

In his life, Halliburton did many great things and took countless unexpected paths. Seeking to transit the famed Panama Canal, for instance, he noted that shipping was charged a transit fee based on weight. Vowing to swim it, he weighed in personally and then dove into the water. When he was done, the transit fee was but $0.36 — the cheapest in history. Likewise, he became a modern Hannibal when he crossed the Alps on an elephant (which he borrowed from the Paris zoo)! Yet his greatest adventure was his flight around the world in an open cockpit biplane dubbed, “Flying Carpet”.

A Non-Pilot’s Global Journey

The only problem was that Richard Halliburton was not a pilot. He had money enough from his writings and lectures, that was sure — even though he was in the first year of the Great Depression. He found a willing, truly expert pilot, but asked him to fly for free, but with ALL expenses covered. For many young pilots, such an opportunity would be hard to pass up today. The other certainty of such a trip was that with a man like Richard Halliburton, the food and lodgings would be second to none. As well, the encounters on the way, friends one would make and experiences would last a lifetime — after all, the famous writer was good friends with Amelia Earhart and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr.

The plane selected for the trip was a Stearman C3B Sport Commercial biplane, which featured a 220 hp Wright J5 radial engine, a great engine that was not cowled. The pilot he selected was named Moye Stephens, a highly experience pilot and instructor. The pair left Los Angeles, California, on Christmas Day of 1930. First, they began a cross-country series of short flights that eventually took them to New York City. As promised, Halliburton covered all expenses — in fact, the costs and expenses of the 18 month journey came in just a little north of $50,000. That might not seem like a lot, but if you correct the value of the dollar in 1930 for inflation, that equates to approximately $690,000 today.

For Moye Stephens, while the rest of America was plunged into the poverty of the Great Depression, he had quite a good job, even if it didn’t pay anything, one might say. With that said, however, Moye Stephens had already been well-employed. A former movie stunt pilot for Howard Hughes (he also taught Hughes to fly), he had taken a job with TAT (later to become TWA) and flew a Ford Trimotor for about $500 a month in salary! The fact that he quit that to fly Richard Halliburton around the world says a lot about how attractive the offer really was.

Adventures and Experiences of a Lifetime

The pair arrived in New York and loaded the “Flying Carpet” into a crate for shipping to Europe (such planes could not hope to safely cross the Atlantic — and certainly not the Pacific for that matter). The pair then boarded the ship for a top drawer cruise across to England. Once there, they began a long, casual and enjoyable journey, flying from place to place as Richard Halliburton deemed necessary and interesting, dining and socializing as they went along, seeing the sights from the air.

They crossed both France and Spain before stopping in Gibraltar, something of a grand European tour. Then they flew across the Straits of Gibraltar to Morocco — and from there on, the flight was certain to be less certain and leisurely. The real adventure was just beginning. At Fez, they arrived in time to participate in the country’s first air meet. Moye Stephens put his movie stunt pilot skills on display with an impromptu aerobatics show in the Stearman, performing loops and rolls for the crowds.

Thereafter, they flew the Sahara to Timbuktu, where Halliburton used his connections to secure access to a fuel cache maintained by Standard Oil. Moving on, they flew to Algeria where they were hosted by the French Foreign Legion. Similar stops and adventures were ahead — Cairo, Petra, Damascus and then into Persia where they offered a ride to the Crown Princess Mahin Banu. Likewise, in neighboring Iraq, they gave a flight to Crown Prince Ghazi. who wanted to fly over his school so that his classmates could see him in an airplane (two years later, Ghazi would take the throne of Iraq). Back in Persia, they met with the famous German aviatrix, Elly Beinhorn, whose Klemm L 26 monoplane with its Argus engine was down with maintenance problems. The pair helped her get flying again (Halliburton’s deep pockets, no doubt, played a role) and the two planes flew onward together east.

Hugging the coastline, the pair of planes arrived in India and made their way to the Taj Mahal. From there, they flew to Nepal and Halliburton, Stephens and Beinhorn circled Mt. Everest in the two planes. While there, Halliburton used the flight to take the first aerial photos of the mountain in history. Back at lower altitudes, they put on another of Moye Stephens’ air shows, this time for the Maharajah of Nepal, who enjoyed the loops and rolls very much. They continued onward to Borneo where they were feted by the Ranee in Sarawak (who also took a flight). As well, they delved into the opposite end of “civilization” and took the chief of the Dyak Headhunters up for a flight. As thanks, the chief gave them a collection of 60 shrunken heads (they later dumped the heads as not a souvenir a too macabre for their trip).

They proceed to the Philippines before finally crating the plane again for the long cruise across the Pacific aboard a ship back to the United States. They arrived at San Francisco, rested and relaxed. There, they reassembled the plane for the last leg of their journey. When they arrived back at Los Angeles, the pair had put more than 33,000 miles behind them over an 18 month period.

Final Notes

After the journey, Richard Halliburton would make good on his investment in the writing of a book that was entitled, “The Flying Carpet”. First year book sales alone brought in $100,000 — not a bad sum for a project during the Great Depression. Before he passed away (lost at sea in a typhoon while on another adventure), Richard Halliburton lectured to over 3 million people, recounting his tales and travels to an always awestruck audience. As for Moye Stephens, he would later join with several others and found the Northrop Corporation.

The Flying Carpet: Adventures in a Biplane

from Timbuktu to Everest and Beyond

If you would like to dive in to Richard Halliburton’s personal adventure, you can get the book today — a wonderful read that reflects the times, a truly glorious period of aviation history.

Buy Print Edition

Dear HW,

I have a copy of ‘The Flying Carpet’ book and it certainly is a fascinating read. I’m sure copies are easliy obtainable on Amazon and ABE Books so I’d recommend any interested in interwar flying to track down a copy.

Nigel Dingley

Where is Halliburton’s Flying Carpet today?

Does his actual Stearman C-3B still exist?

The last record we found of the plane found was in the Netherlands in 1934 in Schipol / Enschede, Netherlands, where it was photographed at a sports flying day. At that time, the plane had painted on the sides of the rear fuselage the name ROSS, and underneath that on an arrow, was painted HOLLYWOOD and underneath that was USA.

ROSS stood for Ross Hadley who owned two Stearmans in the 1930s and flew them arond Europe and even made a jaunt to Singapore at one point. By 1938, however, Ross Hadley is recorded to be flying a Beech D-17S Staggerwing, which he entered in the National Air Races of 1938 (Bendix Race). That plane, with Ross Hadley as pilot, was registered NC18776 and finished 5th place in the race with a recorded speed of 181.84 mph.

About 50 pages to go in Richard Halliburton’s book, “The Flying Carpet”, and WOW, what a great read! The book was given to me as a gift when I was in school in the 1980s from a friend who loved planes. I’ve been waiting for the impulse to read it for 30 years. The book she gave me was originally a gift to her dad 40 years earlier. There is a pencil inscription in the cover, “Mr Stacey from Helene Stacey, Christmas 1935” — I am sure another story and another adventure.

I feel sorry that I waited so long to find my alter ego in the form Richard Halliburton. If you have the time, don’t wait to read it — this book is awesome.