Published on February 19, 2013

During the Great War, in February 1917, the British were on the advance across the desert sands of Egypt and Palestine. Their aim was to liberate the region, including Jerusalem, from the rule of the Ottoman Turks. As the militarily superior British force made gains, the Turkish retreated in order, hoping to be reinforced. Amidst the gains and advances, the Bedouin tribesmen of the region offered their services to both sides, sometimes aiding the British and otherwise accepting payment from the Ottomans so as to foment disorder and banditry in the British rear.

Just such an attack by the Bedouin put the life of a British soldier at risk after a bullet shattered his ankle. Facing a three day journey for medical care, during which he would likely perish, another option was put forward by a volunteer aviator — to fly him to the rear and thus save his life. What followed would be the world’s first aerial medical evacuation — one which has been all but ignored in history.

The Occupation of El Arish and the Battle of Magdhaba

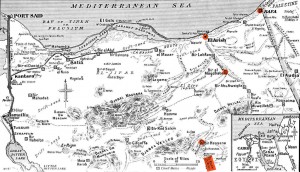

On December 21, 1916, when the British cavalry division of the “Desert Column” entered El Arish, in the Sinai Peninsula. The war against the Ottoman Turks was going well and the Turkish Army, fearing the arrival of the superior British force had withdrawn in two parts, one destined for Rafah and the other for Magdhaba, about 20 to 25 miles east and south respectively. Once having occupied the town of El Arish, the British commanders recognized that they had to exploit the advantage of the newly split Turkish force and capitalize on the momentum in place. Quickly, they elected to attack Magdhaba, bringing the battle to the enemy before an organized and fortified position could be effected.

After an all-night march, the British “Desert Column” and ANZAC forces arrived on the outskirts of Magdhaba. Quickly forming into attack ranks, the force charged into the town at 8:00 am, expecting to encounter 1,600 enemy troops. The British assault was far from overwhelming and the battle raged until approximately 4:00 pm until the enemy finally surrendered. Casualties were significant — the British forces had suffered what was probably 124 wounded and 22 killed (though one source, W. G. MacPherson, writing later in medical review, puts the number of killed as ten less, attributing those as wounded in a like amount). When the dust settled, of the original 1,600 strong garrison, just 1,282 Turkish soldiers had been taken prisoner, the rest had perished. This was a significant victory in the desert war.

The British forces then encamped at Magdhaba and El Arish, sending patrols into the desert. In the meantime, they evacuated their wounded in camel-drawn litters, so-called “camel cacolets” as well as sand litters to the “receiving station” at Kilo 153, an airfield at El Arish that the Royal Flying Corps had established. There, the troops were treated for their injuries.

The Attack on Bir-el-Hassana

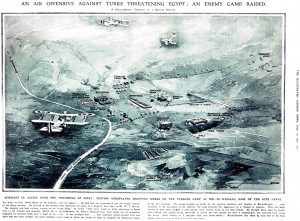

In the next month, patrols in the desert established control by the British forces of the region, though the line had been drawn (temporarily) at Rafah, where the Turks had dug in with the remaining forces. A further attack on January 9, 1917, cleared Rafah and brought it too into British hands. Remnants of Ottoman Turkish forces had retreated to Nekhl and to Bir-el-Hassana, two remote outposts in the midst of the eastern Sinai desert. After tracking the forces by aerial reconnaissance, a decision was made to attack.

On February 17, 1917, the attack was mounted on both Nekhl and Bir-el-Hassana, about 25 miles southeast of Magdhaba. The British 2nd Battalion of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade set out from Magdhaba under the command of Major J. R. Bassett. At dawn on February 18, 1917, the British force arrived — immediately, the small Turkish garrison surrendered, having been taken by surprise and recognizing the likely outcome from the superior British force. Likewise, at Nekhl, aerial reconnaissance proved that the Turkish had already withdrawn, leaving the village undefended, though this word was not passed quickly enough to the commander, who attacked anyway, quickly realizing that there was no resistance. The battle was over but would be marred by a small event the following day, however, when a small patrol near Bir-el-Hassana, where the force was encamped to catch any retreating forces that might come from the area around Nekl, encountered a group of roving Bedouin — it was February 19, 1917, today in aviation history.

The British patrol was ambushed by the armed Bedouin bandits, who had been employed by the Turks. The engagement, as was usual, involved a surprise attack by the Bedouin that, once the British formed up an organized response, quickly culminated in a rapid retreat by the brigands, who disappeared into the desert. In the attack, one of the British enlisted men, Lance-Corporal MacGregor, from the 2nd Battalion of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade, was hit by rifle fire.

The medical corpsmen from the 124th Field Ambulance Str. 26 went to work on the one casualty they had. Quickly, it became clear that the Lance-Corporal needed far more medical care than they could provide. Further, the terrain between Bir-el-Hassana and El Arish was rough and would make for a difficult crossing by camel cacolet. Lance-Corporal MacGregor was in no condition to ride on his own. He had taken a bullet in the ankle, shattering it. A box split was improvised, but the circumstances were dire. Medical personnel doubted that he would survive.

The Aero-Medical Evacuation

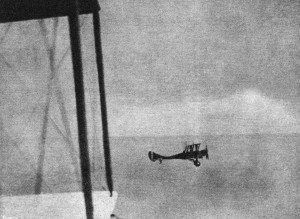

As they discussed options for the injured man, a pilot whose name has been lost to history volunteered to immediately fly the injured man by plane to El Arish. He knew the route well and also knew that the distance could be covered by air in just 45 minutes. His offer was readily accepted.

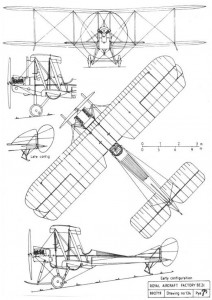

Without delay, Lance-Corporal MacGregor was loaded into the backseat of the airplane, a Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2C, one of a small number that were supporting the British “Desert Column” for observation purposes. As it happened, the flight was completed without mishap or difficulty and landed at Kilo 153, whereupon the injured soldier was immediately brought in for surgery.

Aftermath

Though the world’s first aero-medical evacuation flight had been a complete success, the British Army did not seek to replicate the program. The flight was seen simply as a successful, ad hoc use of aviation and in the rest of the desert war (and in Europe) there were no plans to formalize any aero-medical evacuation units, practices, policies or procedures. In fact, except for sparse mention in a few documents, almost no records exist of the flight itself. Yet from this small start, the promise of aero-medical evacuation flights would flower into one of the most successful uses of aviation in the world today, both in military and non-military settings, saving tens of thousands of lives.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

When did aero-medical evacuation flights become commonplace and under what circumstances?