Published on February 20, 2013

Today we celebrate the birthday of one of aviation’s greatest women, a flyer who, in her long life of 88 years, achieved more firsts, was more influential, and was awarded more citations and medals than any other woman (and probably man) in history. Her life was an almost non-stop adventure of flight, danger and discovery and she dared more things than Amelia Earhart, flew long before Harriet Quimby, and created a legacy that is remains with us today in the creation and organization of the world’s first organized aero-medical evacuation service and certification programs for flight nurses.

This is the story of Marie Marvingt, known as “La Fiancée du Danger”, who was born on this day in aviation history, on February 20, 1875.

First Flights and Adventures

In 1901, Marie Marvingt had her first experience with flight, riding as a passenger in a balloon over the countryside of France. On July 19, 1907, she flew her first balloon as a pilot and in September of 1909, made her first solo flight. By then, she was already a world class sportswoman in mountain climbing, cycling, fencing, swimming and shooting, as well as in a range of winter sports, including ski jumping, speed skating, luge and bobsledding. Denied entry into the Tour de France in 1908 (it was only open to men), she cycled it anyway after the completion of the official race. Only 36 finished of the starting line up of 114 cyclists — she finished it as well with a competitive time. In 1910, the Académie des Sports presented her with the Médaille d’Or — “for all sports”, they declared. Never before and never since has such a blanket “all sports” honor been bestowed upon any individual, yet just such a woman was Marie Marvingt.

In September 1909, she also flew her first aeroplane, a Sommer, and quickly decided to learn the art of piloting. By 1910, she was studying under Hubert Latham and learning to fly in an Antoinette aeroplane, a very difficult task given its instability, lack of power, ungainly control system and general inability to bank effectively in turns. It was the kind of plane that when you saw the tops of the trees, you were relieved because it meant that you would not crash into them.

Flying the Antoinette, she became the second woman to be licensed in a monoplane and went on to fly 900 flights without a single significant crash. Yet there was something else that struck her about the potential of aviation — in a time when flight was considered to be in the realm of sportsman and daredevils, she saw practical uses instead. Thus, she hit upon her greatest calling, to pioneer and organize the field of aero-medical evacuation, flight medicine and in-flight care.

Proposing an Aero-Medical Evacuation Service

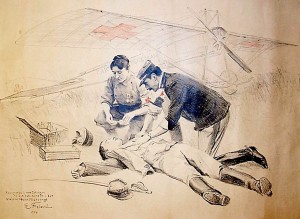

Her pitch to the Government of France on creating an aero-medical evacuation service was welcomed, given her elevated and popular status as a world-renowned sportswoman. Working with the Deperdussin designer Louis Becherau, she pioneered an aeroplane design that was to be purpose-built for medical flights. She began to give speeches in various public forums in order to gain support for the concept and organizational effort that would follow. In proposing her plans, she commissioned a painting by artist Émile Friant to show how care might be given in the field to a wounded soldier, hoping to gain official military support for her venture as war loomed in Europe. Yet it would all come to nothing when the Deperdussin company’s owner, Armand Deperdussin, embezzled the funds and the company subsequently went bankrupt.

With the outbreak of the Great War of 1914, her plans for an aero-medical evacuation organization came to nothing, even if the need was perhaps the greatest it had ever been. Patriotic to the core (pour la France!), she disguised herself as a man and went to war with the 42ième Bataillon de Chasseurs à Pied on the so-called “Western Front”. Discovered after a time, she was returned to civilian life whereupon she volunteered to serve as a bomber pilot. Given her background, she was accepted and thus becoming the world’s first female combat aviator (in this regard, she was a pioneer far, far ahead of her time, as nearly 100 years later, women are still not accepted into combat pilot positions in many air forces!). While flying in the war, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre for a raid on a German base at Metz.

After the end of the Great War in 1918, she rededicated herself to founding an aero-medical evacuation service. After thousands of presentations, and after extraordinary efforts that spanned years, finally in 1934, she was able to establish a service that supported the vast empty deserts of French-ruled Morocco. Her example would spread globally over the decades that followed.

16. Mademoiselle Marvingt sur monoplan Deperdussin.

Source: Contemporary French Postcard

Final Years

In her final years, Marie Marvingt showed little interest in slowing down. In 1955, for her 80th birthday, she flew as a passenger in a two-seat USAF combat jet from Toul-Rosières AB. That same year, she began studies to become a helicopter pilot, though she never completed her ratings. At age 86, recalling her youth as a competitive cyclist, she biked from Nancy to Paris, a distance of about 350 kilometers.

Finally, on December 14, 1963, after a life of adventure and at the age of 88, she passed away in Laxou, France, and was buried in the Preville Cemetery in Nancy. In the end, her life serves as a stunning example of what is possible — both within the glorious field of aviation and outside of it. She lived and died a true “grande dame”.

L’Aviatrice MARVINGT sur son Monoplan Antoinette

Source: Contemporary French Postcard

Perhaps it is best to remember her in her own words, describing the risks that she and other early aviators faced together in pioneering the skies — this from Collier’s Magazine, September 30, 1911:

I find that I am speaking to you of several flights without having yet notified you which was the most stirring. It was beyond all dispute the first that I made alone in my Antoinette, on the 4th of September 1910. For a long time past I had had complete control of the machine with my last teacher, Laffont. I had as much confidence as a learner can have. But, in spite of that, I felt a very unusual and strange sensation. There was a little wind, and I at once rose to a height of 60 meters. The monoplane climbed far better than the one I usually rode in. The first turn caused me real uneasiness, which, at the second, was turned into joy unalloyed. I was rather nervous about coming to earth, but my landing was quite normal. It was done: I had flown.

This new sport is comparable to no other. It is, in my opinion, one of the most intoxicating forms of sport, and will, I am sure, become one of the most popular. Many of us will perish before then, but that prospect will not dismay the braver spirits. In devoting themselves to the new cause, those who have the true aviator’s soul will find in their struggle with the atmosphere a rich compensation for the risks they face.

It is so delicious to fly like a bird!

Indeed, the joy of flight remains one of the finest experiences in life, even today, more than 100 years later.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Who was the first woman to be licensed to fly in a monoplane?

From the Archives

First Helicopter Rescue — a dramatic story of rescue during the Korean War, when a daring helicopter pilot braved heavy ground fire and slipped in to rescue a downed aviator as North Korean soldiers moved in. Read more! =>