Published on February 2, 2013

By Thomas Van Hare

The mission was supposed to have been a two vs. two air combat maneuvering exercise, pitting pilots of the 71st Fighter Interceptor Squadron against one another. Before take off from Malmstrom AFB, the jet flown by one of the pilots, Larry McBride, was forced to abort the mission when the drag chute deployed on the ramp. This meant that it would leave Major Tom Curtis alone against two of his squadron mates, Captain Gary Faust and Major Jimmy Lowe. All three were flying the Convair F-106A Delta Dart. Thus began what was supposed to have been “just another day at the office” for the USAF at the height of the Cold War. Yet the mission that day — February 2, 1970 (today in aviation history) — would soon go down in the books as one of the most bizarre stories in all of aviation history.

The Mission

After take off, they quickly reached the MOA (Military Operations Area) and the flight split up to fly apart. Reaching 20 miles separation from each other, the planes turned back to begin the practice engagement with a head-on pass. Each flight got separate vectors from ground controllers to ensure a fair and even meet up — once they crossed, each pilot could proceed as they wished. As they flew toward each other, Major Curtis decided that his best option was to go after the younger Capt. Faust first. He advanced the throttle and accelerated to Mach 1.90, giving him a speed advantage that he intended to translate into a vertical engagement that favored him.

The flights passed each other at high speed — the fight was on! Immediately, Major Curtis went vertical and watched as the other two F-106As pulled up into him, slower and below. Quickly, he kicked over into a vertical scissors, and pulled wider on each turn to keep his energy advantage, translating speed into altitude, waiting for the others to fall out of the vertical engagement. It was an excellent strategy, giving him a strong advantage against his two opponents, despite being alone and outnumbered.

Entering into a Flat Spin

As they passed through 38,000 feet, Maj. Curtis kicked the plane into a high G rudder reversal to pull into trail behind Capt. Faust. The other pilot responded and also pulled hard in an attempt to tuck inside and counter — his hope was to force Maj. Curtis in an overshoot. Yet Capt. Faust didn’t have the energy to hold it. With a sickening shudder, the plane went into an accelerated stall and then fell off into a post stall gyration. The aircraft rolled violently as Capt. Faust pushed the stick sharply forward, hoping to break the stall. Instead, the plane went into a flat spin. From above, as Maj. Curtis looked down, it looked like Capt. Faust’s f-106 was spinning very slowly as it fell away, its tail rotating in a wide sweep around the tip of the nose probe. It was a flat spin — and most such spins in an F-106 were unrecoverable.

To assist, Maj. Lowe went through the spin recovery procedures over the radio — step by step Capt. Faust followed and repeated the procedures, yet he couldn’t break from the flat spin. The key was getting the nose down to bring an angle of attack that would take the wing out of a stall. He punched the drag chute, which would normally only be used on landing, hoping to lift the tail from the drag — instead, it wrapped around the vertical stabilizer. Finally, as the plane passed downward through 15,000 feet, there were no options left. As per approved procedures, Capt. Faust ejected from the aircraft, high enough to ensure the best chance of survival — in any case, it seemed that the plane was doomed.

An Un-Piloted Descent

Incredibly, when Capt. Faust ejected, the blast force of his seat rocketing out of the plane pushed the F-106’s nose down, instantly breaking the stall and spin. As his own parachute deployed, he and the others could see the plane steady out and fly off in a relatively straight line, wobbling left and right. As part of the procedures to get out of the flat spin, Capt. Faust had set the trim to take off position, which was reasonably close to the landing trim position. As well, he had retarded the throttle to idle. Coincidentally, this left the plane in a roughly good configuration for a steady gliding descent. All three pilots felt that it would likely fireball on impact.

Nonetheless, to see it gliding perfectly was startling. The radio came alive with Maj. Lowe’s admonition, “Gary, you better get back into that thing.” It was a joke, of course, and the real concern was no longer the plane as it flew off toward the sparsely populated plains of northern Montana. Looking downward, the pilots could see that Capt. Faust had bailed out over the Bear Paw Mountains. Rescuing him before he froze to death somewhere down there was going to be a serious matter. The pilots reported his position before returning to base. Luckily, he was rescued and brought to safety by a group of Indians on snowmobiles.

The Landing

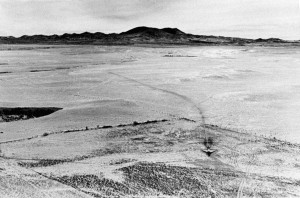

At approximately 175 knots, the plane wobbled its way toward the flat plains and farm fields. Finally, just before impact, it strangely leveled out into a perfect, slightly nose high glide. With the positive influences of ground effect, probably still at about 175 knots, it touched down lightly in a snow-covered alfalfa field near Big Sandy, Montana. Incredibly, it skidded steadily ahead in a perfectly flat position — not once did either wing tip touch the ground as it slowed. Directly ahead was a low stone wall cutting diagonally across the path of the careening jet. As if guided by an unseen hand, the plane suddenly skidded to the right, doing a 20 degree turn and continuing into an adjacent field safely through a gap in the wall.

Finally, it came to a stop. The farmer called the sheriff to report an Air Force plane in his field, its engine still running. When the sheriff arrived, he climbed up on the wing and peered forward into the cockpit. The canopy was gone and the seat was missing. The engine was running and the radar system was still sweeping for targets ahead. He had no idea what to do. Then the plane moved a few feet forward from the engine thrust before again coming to a stop in the frozen snow. That was enough for the sheriff, who hopped down and cleared off to call in a report.

Recovering the Cornfield Bomber

It didn’t take long for the phone to ring at Malmstrom AFB with a request for instructions on how to shut it down. Although the answer was relayed, on the scene, nobody wanted to approach the plane again. It seemed like every time they started to toward it, the snow under the F-106 would melt sufficiently for the plane to suddenly lurch forward another foot or two. Climbing up to reach into the cockpit, directly was ahead of the wing and engine intakes, was just too dangerous. Finally, the small crowd of farmers and law enforcement officers elected to let the plane run out of gas. In all, that took one hour and forty five minutes — then the plane flamed out from a lack of fuel.

The “Cornfield Bomber” had finally ended its mission. The nearest road was straight enough to try to fly it out, but nobody knew what other damage the plane might have suffered in the strange belly landing. The best option was to disassemble the F-106 and truck it out. Back at Malmstrom AFB, it was examined and carefully reassembled. Amazingly, the damage to the plane was all superficial. The skin on the fuselage bottom had been roughed up and part of it had peeled away, but otherwise, the plane was in perfect condition. It was repaired and returned to the flight line where it continued to fly missions with the 71st FIS for another year.

One More Bit of Aviation History

After serving with the 71st FIS, with the disbanding of that squadron, the “Cornfield Bomber” was reassigned to the 49th FIS to fly out of Griffiss AFB. When the last F-106A Delta Darts were retired, the plane was put in storage for a time before heading into the Air Force’s premiere museum. As a result, today you can see the plane, still painted in the colors of the 49th FIS, on display at National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Another famous American, former President George W. Bush, served in the Air National Guard and flew F-106As. What squadrons was he assigned to during his career?

Special Request

Does anyone have a photograph of then Capt. Gary Faust, USAF, or any of the other pilots mentioned in this article? We would like to publish it here.

An incredible story! Thank you for writing about it!

/Sören

incredible story, the truth is that airplanes live!

I may be mistaken but I thought George 43 flew F-102’s with the Texas ANG. Note: A quicky looky at wiki confirms my F-102 qualification citation.

Was this Major the very same Jimmy Lowe as the Jimmy Lowe of Korean War fame?

I have seen a picture of George 43 in the cockpit preparing for takeoff. The aircraft he was in was an F-106A. I worked on F-106s for 19 years. The F-106 and the F-102 are only superficially similar. The pilot has to climb over the intakes to get into the cockpit.

MSgt USAF (ret)

The pilot of the F-102 has to climb over the intakes to enter the cockpit.

MSgt USAF (ret)

Gary Foust is a Junior Vice Commander and member of our local VFW POST 1981, Madera, CA.