Published on March 5, 2013

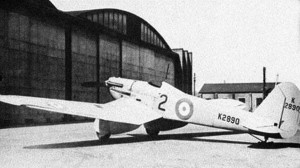

Air Ministry Specification F.7/30 was published in 1930 and called for British firms to prepare designs for a future fighter plane, one that could achieve 250 mph and carry four machine guns. Specification F.7/30 was slanted heavily toward designs that made use of the Rolls-Royce Goshawk II, a V-12 liquid-cooled inline piston engine that boasted 600 hp, which the Air Ministry sought to make its primary powerplant for the 1930s. Among the firms that responded were Bristol, Gloster, Hawker, Westland, Blackburn, and as well a small company called Supermarine, a subsidiary of Vickers, which based its design on its successes in the Schneider Cup seaplane races. The Supermarine Type 224 was thus born and, hoping to win the design competition, the company, known more properly as the Supermarine Aviation Works, asked the Air Ministry to reserve a very special name for the monoplane — “Spitfire”.

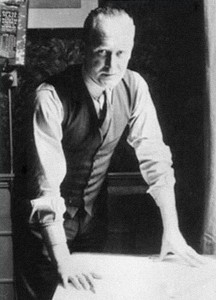

What followed, however, was an abject failure — on its own accord, Supermarine went back to the drawing board and tried again. The design that the company would produce would go down in history as one of the greatest aircraft of all time. This is the story of R. J. Mitchell and his Supermarine Spitfire.

Early Problems

Sadly, not everything would go well with Air Ministry Specification F.7/30. The desired engine, the Goshawk, turned out to be far less reliable than originally hoped. Ultimately, Gloster would win the competition with its biplane Gladiator design, which swapped out the troublesome Goshawk engine for a Bristol Mercury IX radial that boasted a more respectable 830 hp. Gloster’s biplane design would result in contracts to build 747 aircraft, a serious win for the company.

Nonetheless, in reviewing the prototype designs offered under Specification F.7/30, the Air Ministry found merit in the open-cockpit Supermarine Type 224 as well. The Supermarine plane was a monoplane, however, and that didn’t jive well with the RAF’s view that biplanes gave better maneuverability, a critical requirement for a fighter plane. This view was based on their wartime experience in the Great War of 1914 to 1918, which had proved the point perfectly in countless dogfights over the Western Front. The Supermarine 224 offered a gull-wing (think of the later Vought F4U Corsair), which was innovative and shortened the fixed landing gear. Extravagantly streamlined wheel pants minimized the drag effects of the landing gear.

The Air Ministry rejected the Type 224 but ultimately asked if it might be possible to advance the design instead to allow eight, rather than four machine guns. Within Supermarine as well, the Type 224 was seen as a failure, a dog of a design with an unreliable engine and less than stellar performance. Supermarine’s chief engineer, R.J. Mitchell, used the opportunity afforded by the Air Ministry’s interest to call for a completely different aircraft design, though without a contract, it had to be done on the company’s own funding. Leaning heavily on the Schneider Cup racer designs of the late 1920s and early 1930s, Mitchell created an innovative design that featured a graceful elliptical wing and a narrow fuselage that perfectly encompassed another Rolls Royce engine, the Merlin. As requested, eight machine guns were spread out across the wing, rather than bunched together just outside of the prop arc.

The Wing Design

What made the plane so special was its elliptical wing. Whereas Supermarine’s Schneider Cup experiences had all resulted in straight-winged “butter bar” plans, the new design offered speed as well as maneuverability due to the wing shape. Continental European countries seemed to appreciate the changes taking place in aerial tactics and were developing their own monoplane designs. The Germans were developing the Messerschmitt, the Italians had their new FIAT monoplanes, and the French had several single wing designs, such as the Bloch and Dewoitine. As the 1930s advanced, a new theory of high speed fighter tactics was emerging that favored quick, slashing attacks rather than close-in dogfighting with highly maneuverable planes. The Supermarine design was the ideal answer to the newly emerging philosophy, even if the RAF didn’t yet realize that the days of old style dogfighting were over.

In wind tunnel tests, the elliptical wing had proven to be very efficient, producing the maximum amount of lift across the surface area. As well, however, it threatened to have a very sharp, even wicked stall break. Any plane that incorporated such a monoplane, elliptical wing would be highly maneuverable and yet remain streamlined and fast. Thus, in theory, it could execute the types of slashing attacks that were envisioned by more modern aerial tacticians and also hold its own against the highly maneuverable biplanes. With the design completed, Supermarine was finally able to secure £10,000 from the Air Ministry to proceed with building a prototype of its new Type 300 monoplane. With increasing interest from the Air Ministry, another specification was created — yet this time, it was written precisely around the Supermarine Type 300’s capabilities, thus locking out all competition.

First Flights

Supermarine first prototype of the Type 300 was designated by its tail number, K5054 and rolled out in early-mid-1936. The plane was graceful, powerful and looked deadly and fast even when sitting on the ground. After ground run-ups and other tests, Captain Joseph “Mutt” Summers, who was the chief test pilot for Vickers (Aviation) Ltd., the parent company of Supermarine, was called in to perform the first test flight. A fine Spring day heralded the plane’s promising future.

On March 5, 1936 — today in aviation history! — Mutt Summers climbed into the Type 300 prototype at Eastleigh Aerodrome (known later as Southampton Airport). His first flight was, as always with such planes, a short hop just to test only the most basic flight characteristics. It lasted only eight minutes. Nonetheless, Mutt Summers recognized that he was indeed at the controls of something very special — the balance and feel were pure. Both the Vickers and Supermarine representatives knew that it had to exceed all expectations since another monoplane design was vying for the Air Ministry’s attention, a design from Hawker that was being called the Hurricane. The pressure was on as the Hawker design had flown already four months earlier and looked to be positioned for winning the RAF’s main fighter production contract.

R. J. Mitchell’s Most Famous Design

As 1936 drew to a close, the Spitfire’s designer, R. J. Mitchell, was steadily worsening in health. Stricken with cancer which had been diagnosed in 1934, he would steadily turn over the work to another Supermarine engineer, Joseph Smith. The test flights of the Supermarine Type 300 proceeded rapidly and the aircraft showed extraordinary potential. Mitchell was pleased. It achieved a top speed of 349 mph, which resulted in the Air Ministry issuing a formal contract for the manufacturing of 310 aircraft, which they christened the Spitfire, taking the name that Supermarine had earlier requested be reserved for future use.

Not everyone was happy with the name of the plane, least of all, R. J. Mitchell himself, who commented, “Spitfire was just the sort of bloody silly name they would choose.” Even more bizarre was that Mitchell had preferred a rather different name — he would have liked his design be called the Supermarine Shrew (a fat, long-nosed, smallish mole)! It was one of Mitchell’s only errors in judgment in an otherwise extraordinary career of getting it right, time and time again. Ultimately, the name Spitfire would emerge as one of the classic names in fighter interceptor history, made famous on both sides of the war. While the Hawker Hurricane would indeed carry the brunt of the work in the Battle of Britain, the Supermarine Spitfire would have a higher kill ratio and greater survivability. Moreover, its reputation would strike fear into the hearts of the enemy.

Final Thoughts

Famously and at the height of the Battle of Britain, the fighter commander in Germany’s Luftwaffe, Adolf Galland, was asked by Herman Goering what he needed to win the fight — Goering told him to name whatever it was, that he would deliver it. Galland, showing his independent streak, infuriated Goering when he simply quipped, “Give me a squadron of Spitfires.”

The Supermarine Spitfire would go through over 22 major design variations in the following 15 years. In all, more than 22,000 were manufactured under contract. The plane served in dozens of air forces around the world, from the RAF to the RCAF, the RAAF, the USAAF, and many more. During the war and into post war years, it would be used by no less than 33 air forces, including with the Egyptian Air Force, the Israeli Air Force, the Argentinian Air Force, Pakistan’s new air force, and India’s air force. Other countries made good use of the plane, like Sweden, South Africa, Rhodesia, Indonesia, Burma, Italy, New Zealand and Norway.

Ultimately, the Spitfire set the standard in Britain and became that nation’s crowning achievement in fighter plane development at the time. Sadly, R. J. Mitchell would never live to see his beloved Supermarine Type 300 “Spitfire” fly to glory and into the hearts of the British people during World War II. On June 11, 1937, he succumbed to cancer at his home, known as Hazeldene, and located at 2 Russell Place, Portswood, Southampton. He was only forty-two years old. His ashes were buried at the South Stoneham Cemetery in Eastleigh, Hampshire.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The Supermarine Spitfire was not R. J. Mitchell’s final aircraft design. What aircraft was he working on at the time of his death and what became of it?

R. J. Mitchell’s last project was a four engined bomber, the Supermarine B.12/36 project.

As great as the Spitfire undoubtedly was, as far as great designs of that era go, its worth noting that the DH Mosquito was 20 miles per hour faster, and the DH Hornet derivative which came too late to get into the war was even better.

It might be interesting to imagine what would have developed if the war and piston prop fighter era had lasted another 5 or 10 years. The TA 152 long nose Focke-Wulf, Hawker Tempest and Typhoon, Super Corsair, possibly further developments of the Bearcat, Mustang and Thunderbolt.

We can only imagine, but it would have been interesting. The next generation of larger more powerful piston engines was already in development just in case the early jet engines ran into teething problems and weren’t ready as soon as first hoped. Further increases in the octane of aviation gas had already been researched and were waiting on the shelf.

OK, let’s hear your guesses and imaginings.

Regards,

Dave

I bet the R4360 version of the Thunderbolt would have been awesome. It was the XP-72 and was thought to be excellent for chasing down V-1 buzz bombs.

Wing was copied from HE 70 & Baumer Sausweind German planes. Sauswind came along circa 1925. Landing gear is the same as HE 70, as is wing shape & taper angle. Supercharger impellor is French, Cannon Swiss, Machine guns & Carb American, ( Bendix).