Published on March 21, 2013

“NOWADAYS it is safe to remark that any pupil who can keep a fairly clear head and who has quite an average amount of common sense can soon learn to fly. He does not need to be an expert at engineering, or particularly will versed in the aerodynamical considerations underlying the flight of an aeroplane. If he is an expert in both these subjects, so much the better, for with an engineer’s knowledge he should have an engineer’s instinct, and instinct plays a great part in the making of the future airman. A man, to be a good flyer, must necessarily have complete sympathy with his machine. He must not use it harshly, making violent movement with his controlling levers. He must use them gently, and almost you might say, persuasively.”

So began an article regarding the challenges of learning to fly that appeared in Flight, the newsletter of the Royal Aero Club, 100 years ago in aviation history. The details that followed reflected the techniques and thoughts of that era — some remain valid even today, others a bit less so. If you are thinking of learning to fly, read on. Flying has come a long way….

The Challenges

The writer of the article, Lewis W. F. Turner, worked as Chief Pilot of the W. H. Ewen Aviation Co. flight school at Hendon and Lanark, UK. Turner was an early aviator whose first flight was with none other than Grahame-White, and who later attended that aviator’s flight school from February 1911 until receiving his flying credentials on April 1, 1911. Afterward, he immediately became a flight instructor and soon traveled to Russia, where for over a year, he trained new pilots at St. Petersburg.

His writing about flight lessons was clear and concise, though the training process is hardly up to the standards of today’s highly regulated and quite safe training schools. He continued with his descriptive prose, attempting to further attest to the importance of being smooth on the controls when flying:

There is a great similarity between sailing a boat and flying an aeroplane. On a boat, in changing from one tack to another, you swing the rudder round gently but forcibly. If you were to throw it over suddenly, your boat would not answer her helm anywhere near as well. The same applies to an aeroplane, and personally I find that the best results are obtained by gentle and careful manipulations of the lever. Flying, in a gusty wind, sometimes you have to make harsh movements, but that scarcely concern of the pupil, as his work is confined mainly to flying in relatively calm air.

A particularly telling paragraph highlights the true dangers of learning to fly in those early years. Back then, it was rather expected that a student might well crash while learning, particularly if he got “over ambitious”:

As regards actual flying, the pupil who goes steadily, absolutely mastering the points of his first lesson before trying other things which are beyond him, is generally the one who will make the most rapid and thorough progress. Above all, he must pay particular attention to the advice of his instructor. A pupil who is over ambitious rarely gets through his tuition without a smash of some kind, which, although he may escape uninjured, often makes him nervous for some time after, thus, of course, checking his progress. If he does not actually have a smash he will probably come very near to it, and this, most often, has the same effect.

Superstitions and Mascots

It would appear for Turner that a special importance was placed on dispelling myths and superstitions regarding flights — though the bit about three accidents happening at a time is something that, even today, is oft-repeated:

Another thing a pupil will do well to remember is to rely upon himself and his own capabilities, and never trust to luck. He should pay no attention to any superstitious nonsense which is often heard on an aerodrome. One popular superstition is, that when one smash occurs, two others are bound to follow during the day. There is such a thing as your subconscious mind having a reflex on your actions. If a pupil goes out to fly with the idea in his head that, according to superstition there ought to be two other smashes that day, he will probably suffer one of them.

Mascots are much in vogue with some aviators, and although they undoubtedly have some sentimental value, it is of course absurd to believe that they are of any material use in preventing accidents. Personally I have quite a large collection, in fact, if I were to wear them all, I should probably be taken for a Ludgate Hill toy hawker. But whether I wear any or not, my luck, or whatever you like to call it, is invariably the same.

A New Pilot’s First Lessons

Turner described as well how one first began, slowly accumulating the knowledge through first experiences and then qualifying for a first lesson. Today, a quite introductory flight is sometimes taken, but the tradition is to put the new student pilot directly in control of the plane from the first lesson:

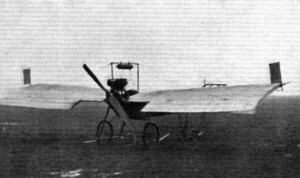

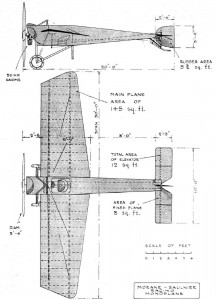

A pupil’s first knowledge of aviation is always to be gained in the hangar, where he can learn the working of the controls and become familiar with the different parts of his machine and their adjustments. Then he is taken up as a passenger by one of the school pilots, and this gets him used to being in the air, and to having an extremely noisy engine just in front or behind him. Incidentally, by keeping an eye on the pilot he will see just what movements are required to correct any variation in the attitude of the machine in the air. After a series of passenger flights he is allowed his first practical lesson, commonly termed “rolling.”

He is put on to a low-powered machine and is permitted to drive it across the aerodrome without leaving the ground. At first he may find a difficulty in keeping the machine on a straight course, but very soon he will pick up the “feeling” of his rudder and be able to run along the ground in a straight line without difficulty from one end of the aerodrome to the other. Having got to that stage, and still keeping up the passenger flight treatment, he is allowed to go out on a higher-powered machine. At first he keeps his engine throttled down and continues to roll until he gets used to being on a different machine. Then he is told to speed up his engine and is permitted to make short hops, using his elevator control gently to lift the machine from the ground and then immediately to return to it.

Final Advice for New Pilots

Turner ended his comments with some practical advice on the actual flying about what to do when the pilot panicked as well as what the final exam consisted of at the time:

In his early flying practice there is a most important point for the pupil to learn, and that is, never to switch off the motor should he find himself in a difficulty. On a motor car, if there is some difficulty ahead, it is usually right to throttle down the engine and throw out the clutch. But with an aeroplane it is the reverse, for the greater the difficulty you get into, the greater is the engine power necessary to get you out of it. Gradually the lengths of his hops increase, until he is capable of making straight flights the full length of the aerodrome, keeping a few feet off the ground. He is kept at this for some little while, increasing the height of his flights as he gains confidence. The pupil should not be hurried over this stage, because, above all, he is getting good practice at vol plane’s, and landings, which are very important.

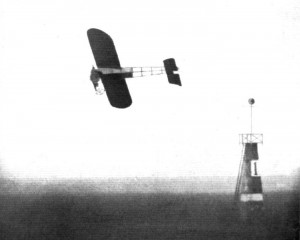

By now the pupil has virtually come to the end of his school tuition, and all that remains to be done is to advise the Royal Aero Club of his readiness to be examined. In his tests he will be required to make two distance flights, each consisting of five figures of eight, flown round marking posts situated not more than 500 metres apart. He must also make an altitude flight as I have mentioned before, going up to fifty metres, but this may be included in one of the distance flights. On each occasion he must land within fifty metres of a predetermined point, and must not use his engine again after touching ground. Providing he has satisfied the R.Ae.C. observers, he may consider himself a fully qualified pilot, and, in consequence, being pleased with himself and with everything in general, he will undoubtedly follow the usual course of running up to town and standing himself a very excellent dinner on the strength of it.

Looking back on it, one can be very pleased with the far more advanced training that 100 years of flight training experience has brought about. Perhaps future generations, however, will look at our own procedures today and wonder at how things once were.

I suppose all that was left was cutting off the shirt tail of the pilot at that point!

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

When a pilot solos in today’s era, it is tradition to cut his shirt tail — when did that tradition start and why?

Create some cloth to make the epaulettes for the addition to their uniform.