Published on March 28, 2013

The Armstrong Whitworth A.W. 154 Argosy II “City of Liverpool” was one of the key aircraft serving with Imperial Airways from Britain. The airline crisscrossed Europe, offering a luxury “Silver Wing” service to Paris, flying to Berlin, stopping at Belgium and setting a high standard for others to match. The Argosy Mk II, with its three engines — each a 420 hp (310 kW) Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar IVA radial — had served well since 1929 alongside the earlier Mk I models, carrying up to 18 passengers on each flight with just a crew of three. Yet on March 28, 1933, one of the aircraft would suffer a catastrophic inflight fire, crashing into the fields of Diksmuide, Belgium. Twelve passengers and three crewmen would perish as a result. At the time, it was the greatest airline disaster in British history.

While tragic, the investigation that followed pointed to a possible darker, more sinister cause than an accidental fire — compounding the suspicion was the fact that a German dentist, Dr. Albert Voss, was seen to jump from the aircraft before it hit the ground. As he had no parachute, he too died in the accident, though there was more afoot than most realized at the time. Only later would Dr. Voss’ brother relay his own suspicions, revealing a bizarre tale of drug smuggling and illegal activities — it was a story that pointed to the likelihood of sabotage….

Imperial Airways and the Argosy

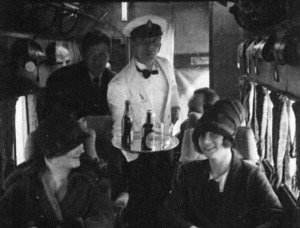

Over the years it was in operation, among other aircraft, Imperial Airways acquired seven of the Armstrong Whitworth A.W. 154 Argosy type — three were Mk I and four were Mk II types. The first came into service with the airline in the mid-1920s. By 1935, however, the aircraft was outdated and was replaced with newer, more modern types. Yet during those years — nearly 14 years of service with the Argosy fleet — Imperial Airways established a new standard for airline service throughout Europe. For instance, by the late 1920s, some of the aircraft had two of the seats removed and replaced with a bar in the rear of the plane. A bartender served the passengers while in flight!

- The Argosy G-AACI taking off from a field on a passenger flight, c.1933.

The planes were large and inspired confidence among passengers about the safety record of the airline. Even the shape of the fuselage, which brought to mind small scale rail carriages, played on the passenger’s perceptions of the new opportunities available. Flying from place to place rather than traveling by ship and car was becoming common. Businessmen relied on Imperial Airways to connect themselves with far flung enterprises, to make deals and acquire products, buy raw materials and components for their own ventures. A face to face meeting was possible after only a short flight.

And thus, in 1933, when Imperial Airways took off on that fateful day, a mix of passengers was on board, including regular travelers. Security was the least of anyone’ concerns — gate checks, baggage inspections, prohibitions against smoking and against carrying on weapons, precautions against hijacking — all these things were far ahead in the future.

Analyzing the Crash

When the Argosy Mk II — G-AACI — crashed, investigators traveled quickly to the scene to try to figure out what had happened. They found the wreckage strewn across a field at Diksmuide, Belgium. They soon discovered that the plane had suffered a fire in the rear fuselage, perhaps severing control of the tail surfaces or causing other catastrophic damage that forced the plane into a terminal dive. Based on eyewitnesses, the pilots had attempted to descend for an emergency landing but hadn’t made it — just 60 meters high, the plane exploded and broke apart. Prior to striking the ground, one of the passengers, Dr. Voss, was observed to leap from the plane and plummet to his death. Thereafter, the plane exploded and split into two pieces, each coming down separately.

In looking through the debris, the investigators were able to establish with certainty that the fire had not been caused by a fuel leak or other problem with the engines. Though evidence was lacking to confirm the exact source, the best guess was that some sort of debris or object had been either intentionally or inadvertently set afire in the rear of the airplane. The conclusion was characteristically certain, as many aviation investigations are, that the cause almost certainly involved some act of a passenger or crewman.

To that date, however, there had never been a single act of aerial sabotage in history. Was it the case in this crash? The investigators wrote up the report in terms reflecting what they knew, not what they suspected:

“Named City of Liverpool, aircraft left Brussels-Haren Airport at 1336LT, late of 30 minutes on its scheduled time. It overflew Gent at 1400LT and was approaching Roeselare. While cruising at 4,300 feet and 95 knots, radionavigator informed ATC that all was OK on board. Few minutes later, a fire broke out in the cabin. Immediately, crew reduced altitude to perform an emergency landing but at a height of sixty metres, aircraft stalled and crashed in an open field. Nobody survived.”

The report then continued with a brief section describing potential causes:

“Investigations revealed that no technical failure occurred on wings or engines. A quick and violent fire broke out in the cabin, maybe in a luggage or in the toilet compartment for unknown reasons. This fire was very intensive as no one in the cabin was able to use the fire extinguisher. Investigators thought about a criminal act but Imperial Airways declared few months later that the responsibility of any passenger could not be determined.”

The Story of Dr. Voss

According to the brother of Dr. Voss, the good dentist had been involved for some time in illegal drug smuggling, traveling around Europe on aircraft and using his status as a dentist to acquire drugs that he then resold on the black market for unlicensed uses. The smuggling had been profitable, even if completely criminal. For their part, the police were slowly tracking the leads and evidence to unravel the secret drug business of Dr. Voss, using Imperial Airways as his means of traveling about Europe.

By 1933, the net was tightening and Dr. Voss realized that the police were on hot his tail. According to the brother, it was then that Dr. Voss hatched a plot to set a fire on board the Imperial Airways flight, hoping to escape either just before the crash or to survive the crash and walk away from a burning death trap in which other passengers would perish. He apparently hoped to escape unnoticed and be assumed to be among the charred bodies and lost among the scattered pieces. Then, it was alleged, he could simply establish a new identity elsewhere and, he hoped, the police investigation would end there.

Final Thoughts

Who can tell whether the tale of Dr. Voss and the sabotage of the Imperials Airways plane, “City of Liverpool” was true? What we do know is that with the sabotage of this one airliner, the business of aviation would embark into a new era of steadily increasing threats, where bombings, sabotage, drug smuggling, hijacking and even more horrific practices would steadily erode the bright star of aviation’s purity and seemingly untouchable status. In the end, airplanes are tools of technology that involve people, with all of their failings and glories. It would have been amazing had aviation remained above it all, separated from the shadowy tendencies of human nature and ill will — but it was not to be.

Whether the flight was downed by sabotage or accident was ultimately not important. The world changed that day anyway. A new road was ahead, with ever increasing security protocols and new inspections, new restrictions and new checks. Today, it seems that the only question remaining is just how far it will all go. Perhaps full body scanners won’t be enough anymore and they will be looked upon in future years as the beginning of a new level of intrusive security checks. Only time will tell whether it was all worth it.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What was the last role of the Armstrong Whitworth A.W. 154 Argosy in the history of aviation?

A dark bit of aviation history there.

Thanks!

Yes, the dark bits of the history have given us the “prevention” for the future.

Its nice to read an article on this. My great grandfather, Charles Frederick Rowsell, died on that plane. Unfortunately, he always took trains or boats but for some reason that day, he took a plane, which turned out to be his first and last flight! I would be grateful if anyone could let me know if I can find out if any remains were ever recovered and if these are located anywhere.

Regards,

Daniel Rowsell

Hi Daniel,

I’ve been researching the topic of the City of Liverpool. The crash happened about 8km from where I live and with the help of a few local history experts I was able to determine the location of the crash site which I visited yesterday. The building behind the wreckage in the fourth photo is a castle which still exists. In fact the water from the garden pond was used by the responding fire brigade to extinguish the burning wreckage. It appears as though the crash site is largely undisturbed. According to a period newspaper article, after the bodies were removed, the site was opened to the public. Undoubtedly, pieces of the aircraft are floating around in personal collections. Feel free to drop me a line if you’re interested. Would love to find out more about your great grandfather.

Take care,

Wout (badaboehm@gmail.com)

My great grandfather was Albert Voss. We don’t know a great deal about him other than this.

Hi David,

Please shoot me an email when you have a chance. I did uncover some information about your grandfather (including his British naturalisation certificate) which I’d be happy to share with you if you don’t already have it. Do you have any photographs of him?

Best wishes,

Wout Wynants

badaboehm@gmail.com

Yes, no telling where Dr. Voss would have tried to hide in today’s era of technology (SanSal). It would have been tough for him to pull this off with today’s security measures.

I’ve only just found out that Albert Boss was my great grandfather!! Still searching for other records of him.

Albert Voss’ brother clearly loathed him for some unknown reason. Albert Voss had purchased air accident insurance before he left Brussels. On the face of it, this seems a strange thing to do if he’d wanted to disappear. His next of kin would want the money and the insurance company wouldn’t pay out without a body — thus highlighting the anomaly of the missing passenger.

My great grandfather, Lionel Leleu, was the pilot of the plane the day it crashed. We even have a statue of this plane in the house, which my great grandfather used as a hood ornament for his car not long before he was involved in the crash. Despite this, all I know about the events of that day comes from a single newspaper report from that time and a photograph of his funeral. If anyone has anymore information or photographs of the events of that day I would be very interested to see it. Thank you.

My great-great uncle Sir John Rowland was on this flight and like everyone else I would like to know more.

Sir John was also my relation. He was my grandmother’s cousin.

Sir John was my grandfather. I am starting at this late stage of my life to look into family history a bit.

David