“Compared with the previous Easter’s meeting, the weather conditions were, on the whole, not anything like so favourable this Easter, yet the exhibitions of flying that were given on the Friday and Saturday alone far and away exceeded any previous flights seen at Hendon. Although we have to record one nasty accident — described later — to that plucky young aviator, Marcel Desoutter, everything otherwise went off without a hitch, while Desoutter — the victim of one of those annoying accidents caused by an insignificant slip — is, we hear, well on the way to recovery. What was most gratifying, however, was the number of visitors — and amongst them were to be seen a number of distinguished personages — and cars that lined the enclosures, for it must be remembered that, except for Sunday, the weather was not ideal for standing about in the open.”

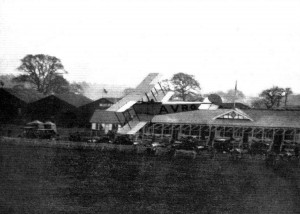

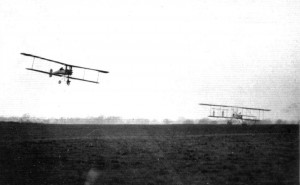

One hundred years ago today in aviation history, the English were engaged in Easter flying out of the London aerodrome of Hendon. The tradition of Easter flying, by then in its third year, had grown with each passing holiday. The year of 1913 was no different as the full range of aircraft were wheeled out of their hangars for flights by the many famous aviators of the day. Rides were given to members of the public and to family and friends, including some given away in a drawing through the Daily Mail newspaper. On the whole, it was quite a weekend, despite the rather poor English weather — though there was that little business with Desoutter’s mishap….

Flights on Easter

The types of planes were a stunning round-up of English early aviation history — among them was a Farman biplane, flown by Louis Noel, had been built by Grahame-White and featured a 70 hp Gnome. As well, Pierre Verrier made a good showing with a 70 hp Maurice Farman while G. I. Temple flew a Caudron type with just a 35 hp engine, imported from France.

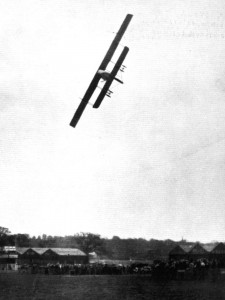

Friday was not at all promising, the wind and rain being simply appalling early in the afternoon. In spite of this, however, quite a number of people assembled, both inside and outside the aerodrome, and patiently braved the elements on the chance of seeing some flying. They were well rewarded for doing so, for at about four o’clock the weather cleared up a bit, although the wind still blew at about 35 or 40 m.p.h., and Marcel Desoutter ventured out on the old 50-h.p. Gnome-Bleriot monoplane. He was followed by Manuel Chevillard on an 80-h.p. (Gnome) Military Henry Farman biplane, who gave an exhibition which would be impossible to describe in words. He started off with a series of zig-zag switchbacks, the biplane swaying from side to side at the same time.

If you were wondering just how Chevillard’s exhibition might have looked like, the article includes a description of his death-defying dives, which were meant to entertain onlookers by their appearance as dangerous and daring, at the very edge of control.

He then ascended with remarkable rapidity and executed one of his astonishing dives. This can only be described as a “side-dip” with the machine banked at about 70° or so. As far as one can see in the short space of lime it takes for this dive to materialise, what happens is as follows: the pilot first banks the machine to about 6o° and then it swings sharply round on its lower leading wing-tip until the higher wing-tip is again level with the former, the machine still diving. It appeared to the writer that during one of these dives he observed the biplane bank “beyond the vertical,” only for a fraction of a second, it is true. After two of these sensational dives, Chevillard brought the machine to earth, making a beautiful landing.

Other Aerial Maneuvers

As the weekend drew on, more and more aeroplanes and people came to Hendon for the Easter flying that year. The flights continued, some with daring twists and others seeking to set new records, such as for time aloft or altitude attained. Those were difficult, however, as the weather did not cooperate — it was England in the Spring, after all.

Saturday was again very stormy, notwithstanding the promise of a fine day in the morning. By 3 o’clock a large crowd had arrived at the aerodrome, and with it the wind, which was by then quite unfavourable for racing. At 3.30, Chevillard ascended on the 80-h.p. Henry Farman biplane for an attempt at the altitude contest. He rose fairly quickly, reaching a height of about 1,000 ft. in five or six minutes. Higher he could not get, for the wind was very strong at this height and beat him down again and again, to he gave up any further attempt and descended with one of his spiral side dives, which looked appalling at the height from which he came. On landing, it was ascertained that he had attained a height of 1,050 ft.

As the afternoon’s weather steadily degraded, flying wound down, though there was yet another surprise in store for the assembled public and aviators:

By this time the weather was getting more and more threatening, and some excitement ensued when a biplane, flying very low, was seen approaching the aerodrome. This was Gordon Bell and his mechanic on the new Short machine (50-h.p. Gnome) whom, as was previously announced, had left Eastchurch at 2.45 p.m. He landed in the aerodrome at 3.55, having had a terrible journey. After this, Pierre Verrier made a four-minute flight on the Maurice Farman, and a little later a plucky flight was made by Spratt on the 35-h.p. Anzani-Deperdussin monoplane. He handled this small machine in the high wind with great skill and deserved far more applause than he got.

An attempt was then made to run a speed handicap between Verrier and Chevillard, but a sudden downpour of rain settled the matter once and for all, and the machines were hurriedly returned to their sheds. The Short biplane, however, was too late in obtaining shelter, for a terrific gust of wind came up with startling suddenness and lifted the machine right off the ground, turned it completely over and then dashed it to the ground with such force that the propeller was embedded some 14 inches in the ground. Some considerable damage was done to the machine, the tail being smashed completely. No more flying was done that day, and there were some doubts as to the chances of flying the next day, Sunday.

Easter Sunday Flights

Unexpectedly, Sunday dawned to beautiful weather and promised a full day of flying for Easter of 1913. The day was celebrated by all in classic fashion, beginning with morning flights and continuing until nightfall. The morning’s flights, however, were marred with an accident by Marcel Desoutter:

However, thoroughly ashamed of its behaviour the previous day, the weather was perfect on the Sunday, with the result that there was a large attendance and plenty of good flying, marred only by the accident to Desoutter at the commencement of the afternoon. Desoutter had started the first flight, and had been flying for about 15 minutes when he descended to about 30 or 50 ft. from the ground. It was at this height that the monoplane suddenly dived to earth when at the far end of the aerodrome. The ambulance corps and doctors were on the spot with notewoithy promptness, and soon had the unfortunate young pilot attended to. It was found that he had received a compound fracture of the left leg and some other minor injuries. He was removed to the hospital near by. The cause of the accident appears to be that he was reaching for the pressure-pump with his right hand when the cloche slipped from his left hand and fell forward before he could regain control. The accounts of the accident which have appeared in the daily Press are more picturesque than accurate.

The rest of the day included many high points as the flyers put on a good show. A short description followed:

The pilots and machines were Chevillard on the Henry Farman, Verrier on the Maurice Farman, Georges Collardeau — his first appearance in England — on the Breguet, Lieut. Lushington on the 80-h.p. Gnome-Caudron, Lewis Turner and Temple on Caudrons, Noel on the 60-h.p. Grahame-White tractor, and Gustav Hamel on the Blériot. The latter was the sole representative of the monoplane, all the other machines being biplanes; Hamel had flown over on this machine during the afternoon from Brooklands, having taken 13 1/2 minutes for the journey. The new Grahame-White biplane made a very promising flight, but some slight damage was done to the chassis on landing.

The Final Day — Monday

“Monday’s meeting was by far the best, in fact, it was one of the most successful meetings they have had at Hendon since the aerial Derby. About 20,000 people were present — the number of cars being unusually large — while large crowds gathered outside the aerodrome and on Hendon Hill.”

The public enjoyed some rides and additional aerobatic flights:

After this event the eight “Daily Express Ladies” were given their joy flights. This proved to be an interesting and amusing event. Chevillard and Verrier took them up one after the other in a remarkably short space of time — although the flights were by no means short. Lewis Turner also took up one, Miss Prudence O’Shea of the Gaiety. All expressed themselves delighted with their experience and wanted encores.

The flyers made a series of speed races that day — and above all, the final race was the best:

The final was one of the best races ever flown at Hendon. Verrier, who had 43 secs. start, banked his machine in splendid style round the pylons. Collardeau slowly, but surely, caught up his rival, so that in the last lap he almost passed Verrier at pylon No. 6; it seemed at first that the Breguet was ahead as the finishing line was approached, but, as a matter of fact, both machines passed the line simultaneously. Great was the excitement when this heat ended, but the verdict of the judges was received with good feeling, and it was decided to fly another heat of four laps to decide the awarding of the gold and silver medals, the money prize being equally divided between them. In this last heat, Verrier got 22 secs, start, and won by 10 1/2 secs. A short flight by G. I. Temple on his Caudron biplane, and late in the evening, a joy-flight by Verrier on the Maurice Farman, concluded the very successful four-day meeting,

Ultimately, is there a better way to celebrate the Easter holiday than that?

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The French pilot Collardeau’s Easter trip to England was his first across the English Channel. What became of him after the events of Hendon?

I have got a very old postcard with a plane and two gentlemen standing on the right side. underneath stands; M Verrier – London Aerodrome – Hendon.

I am from Namibia in Africa and this came out of a old family album and it seems to be sent in 1912.

Can you possibly help to direct me where to find out if it has got any value.

Thank you so much.

Rina Knight