Published on March 7, 2013

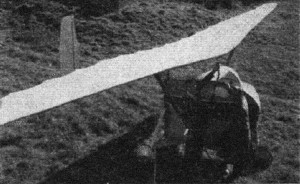

The household vacuum cleaner ran smoothly for 25 minutes, slowly pushing air into the inflatable, collapsed wing, which would span 27 feet once filled. Incredibly, the wing and airplane together weighed just 38 pounds without the pilot. It featured a wing area of 250 square feet and carried no engine. Instead, the pilot would pedal to turn the prop and get the aircraft into flight. It was a far cry from Paul MacCready’s Gossamer Albatross of 1979, which had successfully flew across the English Channel, or even his earlier Gossamer Condor which achieved a one mile figure eight course in 1977. In fact, it could barely fly even a few feet in ground effect. Of course, the later lightweight carbon fiber wing spars and Mylar wing coverings had not yet been invented at the time it flew — more importantly, however, the design was inflatable, rather than rigid.

The year was 1956 and Daniel Perkins had flown his inflatable winged airplane. Indeed, something very special happened today in aviation history, on March 7, 1956. As astonishing as his success was, Daniel Perkins was not the first to undertake inflatable airplane experiments. This is the history of inflatable airplanes.

Daniel Perkins and his Inflatable Airplanes

In the early 1950s, Daniel Perkins set himself to solving the problem of an inflatable airplane. As an engineer with Britain’s Royal Aircraft Establishment, located at Cardington, UK, he was ideally suited to the task. The primary goal was to develop a man-portable aircraft that could be deflated, rolled into a bag and carried from place to place, either by hand, in a motorcycle or by car — in the “boot” as the English like to call the trunk of a car (my English friends remind me that elephants have trunks, not cars). Ultimately, he elected to roll the plane up and hang it from the front of truck, right off the front bumper!

Perkins’ first effort was tested in an 800 foot wide airship/dirigible hangar, thus negating the outside effects of wind and weather. Pedaling hard, his pilot could achieve short and medium distance “hops”, taking off and flying in ground effect, but was unable to climb higher. Put simply, the power available from a single person pedaling hard, competing against the drag profile of the plane, meant that even a champion cyclist couldn’t quite fly long enough to make the design viable.

Based on the success of that design, Daniel Perkins tried a number of variations and new designs, including some that were fully inflatable. To save on weight, he experimented with flying wing designs as well. These proved somewhat successful, but never quite achieved long distance, reliable flight. His best effort was what he named the Reluctant Phoenix, which weighed but 44 pounds and first flew on July 16, 1966. His best flight in the Reluctant Phoenix achieved 420 feet, rising to an altitude of 2 feet — yet even this was farther than the Wright’s first flight in 1903!

Earlier Inflatable Planes

Daniel Perkins wasn’t the first to experiment with inflatable planes, however. Long before — actually decades earlier — Taylor McDaniel started work on an inflatable rubber glider in 1931. His experiments with inflatables, which were likely the first in history, proved the concept and pioneered many innovations that would later be used by others — among the best solutions was to use inflatable rubber tubes as strengthening members within the wings and fuselage.

McDaniel’s test pilot was Joe Bergling and, incredible as it sounds, one of the goals of the test program was to demonstrate that the plane could be nose-dived into the ground in a crash landing. It was hoped that due to the soft nature of its inflatable components, the plane and pilot suffer no damage in the resulting crash. Pilot Joe Bergling was able to demonstrate that fact successfully!

Just a few laters, the Soviets began work on an inflatable aircraft for their infantry forces that could be carried by two men in a large bag, unpacked and rolled out, inflated and flown with the aid of a small reciprocating engine. Created by P. Gorokhovsky, who worked in the Experimental Institute of the Commissariat for Heavy Industry, the idea was to fly the inflatable plane behind enemy lines, carrying soldiers into the enemy’s rear. The plane would then be deflated and trucked back after victory. This was in 1935 and at the time, the Soviets held most of the world’s gliding records, demonstrating an extraordinarily advanced glider design industry — their design was thus an inflatable glider with supplemental power.

Strangely, the Soviets were hellbent on militarizing gliders above all, and an inflatable glider filled the box for an infantry weapon that would dramatically enhance mobility. Their inflatable plane, as such, was more like a glider with supplemental power — it worked and the Soviets were able to fly a number of tests to prove the concept. Overall, however, it became clear that the inflatable powered glider airplane didn’t really have much future as a serious weapon and the concept was abandoned (at least for delivering individual infantrymen behind enemy lines. Inflatable gliders without power, however, showed promise and the Soviets continued in that direction, even developing the world’s first cargo glider called the Glider 6-63.

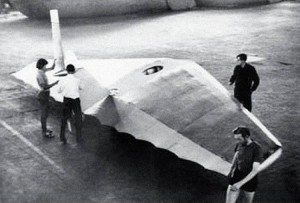

After the Soviet efforts, several decades would pass before others tried their luck with inflatable airplanes. When the inflatable plane concept was brought back, it was to save lives. During the Korean War, the USAF had seen how often downed pilots couldn’t be rescued before their capture by the enemy. The idea evolved to an inflatable plane that could be rapidly airdropped to a downed pilot who would unpack it, inflate it, start the engine and fly himself to safety. A contract was issued to the Goodyear Aircraft Company to develop the concept — it was code named the GA.468, but commonly called the Inflatoplane.

The Goodyear Inflatoplane

After a 12 week development period (incredibly fast), the Inflatoplane was ready for its first test flight at Olathe, Kansas, on May 28th, 1957. To achieve such rapid success, Goodyear’s engineers had borrowed heavily from the experiments completed by Taylor McDaniel with his inflatable rubber glider of 1931, much of which was revealed in McDaniel’s expired patents. Goodyear’s test pilot, Richard Ulm, was tasked to test the plane. The test flight program got interesting when Ulm got caught in a fast evolving Midwestern thunderstorm — he survived somehow and brought the plane down successfully. Later, another of the test pilots was not so lucky. Army aviator Lt. “Pug” Wallace had a control wire in the wing break and foul in a pulley, locking the stick hard over and causing a loss of aileron control. The Inflatoplane steadily tightened its turn until finally the wing loading exceeded the inflated spar’s rigid strength limit. At that, the wing folded up over the top, hitting the propeller, which shredded the rubberized fabric. As the plane nosed over into a spin, Lt. Wallace bailed out but was killed when his parachute didn’t open.

Ultimately, twelve of the Inflatoplanes were built, including a two-seat version in 1959. Though the program never got the green light for large scale acquisition, testing continued on DoD contracts until 1973 when the program was cancelled. Among the inflatable airplanes, Goodyear’s aircraft was perhaps the most successful. Others would follow with ever more modern designs, using new materials and with better engine technologies — but that is another story.

Watch Videos of the Goodyear Inflatoplane

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What famous Soviet space engineer got his start designing gliders for the Soviet military?

My grandfather was Taylor McDaniel, I was nine years old when he passed away 1952. I still have many good memories of him. His wife Ida McDaniel Passed away in 1981. He still has one son living Thomas McDaniel he lives in Lake Mary, Florida.

Peggy,

My Grandfather was Joe Bergling, the pilot of the 1931 glider crash.

Joe passed away in 1999. He spoke of the test flights on Hoover Field often.

27 feet and weighed just 38 pounds that’s amazing for the time!

Thanks for putting all this together.

Take care

Jamie