Published on March 30, 2013

When the pair of Portuguese flyers left Lisbon, they were confident of the voyage ahead. Their aircraft, a single engine, open cockpit, Fairey IIID biplane on floats, was one of the Portuguese Navy’s finest. The date was March 30, 1922 — 91 years ago today in aviation history. As the plane lifted off, the clock registered precisely 7:00 am GMT. Ahead was the most daunting and difficult challenge yet flown in aviation history. Their mission, supported by the Portuguese government and navy, was to fly across the equator and over the vast South Atlantic, stopping along the way at several island groups, to link Lisbon with faraway Brazil. The flight involved over 5,200 miles of flying, much of it over water in an airplane that at best had a 1,500 mile maximum range. There would be many stops along the way.

The challenges of the flight would push the men and equipment to the limit and beyond. Two aircraft would be lost and the men would take the third and last plane on its final flight into history — one way or another, the story of the Longest Flight would write the name of Gago Coutinho, the navigator, and his pilot, Sacadura Cabral, forever into history.

The Plan and Method

The planning for the flight was intensive, starting in 1920 when Sacadura Cabral traveled to England to acquire a set of three specially modified aircraft. Although Cabral rather preferred French aircraft, the English-built Fairey IIID hydro-aeroplane type was selected because of its reliable Rolls Royce engine and the willingness of the factory to make the modifications required for long range over water flying. Two years later, by the end of 1922, the plane was ready. The two men, both senior officers in the Portuguese Navy, returned to Portugal to prepare the final plans for the flight.

Both Coutinho and Sacadura saw the challenge as a way to prove the new techniques of long range, over water aerial navigation rather than as some sort of adventure. Like the great Portuguese explorers of the Golden Age, they approached the task as a major expeditionary voyage. They sought primarily to prove that airplanes could be navigated with the same precision as ships, despite their unstable nature, making it difficult to take celestial sightings. If this could be done, they felt that Portugal could open the world to aviation, taking flight beyond the limitations of pilotage with reference to landmarks. Their ultimate goal was to prove that pilots could go anywhere, navigating solely by the sun and stars. It was a tall order and one which many doubted could be done.

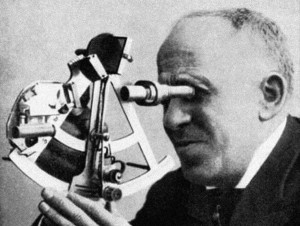

The most serious problem had to do with the difficulties of shooting a celestial position by sextant from aboard an airplane in flight. Charting an accurate position at night from an airplane, with no reference to a horizon, was impossible at the time. With the seasoning that can only come from decades of naval service, Gago Coutinho developed a revolutionary modification to the instrumentation of the sextant, adding a pair of spirit levels that together allowed the navigator to establish an artificial horizon. Even with the movement of the plane beneath him, he could shoot a precision position, allowing him to find the island way points along the route. If he was wrong in his positions, however, there would be little hope of rescue.

The first leg of the planned voyage spanned 850 miles from Lisbon to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. A second flight of 920 miles would take them to São Vicente, and finally a short hop of just 160 miles would bring them to Porto Praia on Santiago Island. From there, they would take the longest flight across to the Brazilian islands of Fernando Noronha, a distance of 1,425 miles. That would be the greatest challenge as after that, all that remained was to fly a series of short hops down the coast of Brazil until they reached Rio de Janiero.

Along the way, for fuel and maintenance, the Portuguese Navy provided a support ship, the naval cruiser NRP República to sail after the plane from stop to stop. Thus, the aviators would fly ahead to the next set of islands off the African coast and, landing there, they would wait for the NRP República to arrive — though that would be days later. In the interim, they would rest, prepare for the next leg of the voyage, and do a bit of maintenance on their plane if needed. When the ship arrived, they would refuel, do any heavy maintenance with the help of the men on board the ship if it was required, and then take off for the next set of islands.

Island to Island in the Longest Flight

On March 30, they took off in their primary airplane, which they had christened the “Lusitânia”. They departed from Bom Sucesso Naval Air Station at Lisbon. Taxiing out onto the Tagus, near the Belém Tower, Sacadura Cabral slowly added power and accelerated smoothly over the waves. After just 15 seconds, they were airborne. They turned to the southwest toward Las Palmas. Just 22 minutes later, they were out of sight of all land — now their lives were in the hands of Gago Coutinho and his sextant. At noon, Coutinho shot their position as 31º 27′ N x 13º 44′ W. Working out the mathematics, they computed an average ground speed of 81 mph. At 14:15 they spotted the Ilha Selvagem Grande in the distance, 50 miles away. At 14:57 they spotted the northern tip of Tenerife. Thereafter, it was easy navigation around the island to find the Purerto de La Luz, which which they located at 15:37. Coutinho’s navigation was excellent.

They flew over to nearby Gando to facilitate a better take off with a full load. They were troubled by two factors — first, their fuel consumption was 20 gals/hour, in other words, higher than they had planned or expected. Second, the seaplane’s twin floats had taken on water. They realized that the two problems were related — the latter was the cause of the former, as the heavier load meant that their fuel consumption was higher than planned. After some calculations, they also realized that since the floats were leaking they would not likely remain afloat long along the way at the more remote stops. Lacking any way to drain the floats or get the plane out of the water, they were left to ponder the singular impossibility that they could not make the planned trip to the islands of Fernando Noronha. Unless their fuel consumption could somehow be reduced, they would fall short, out of fuel.

From Gando on April 5, they flew next to São Vicente, managing it in 10 hours and 43 minutes of flight time. Given the distance, they averaged 79.5 mph ground speed, once again proving that the extra load of the water that had seeped into the floats was reducing their range. The fuel tanks could carry just 330 gallons and at 20 gph, their maximum flight time was 16.5 hours, with no reserve. At 80 mph, they could make it only 1,320 miles at best — yet the next leg of the trip to the islands of Fernando Noronha was 1,425 miles. They would be nearly 100 miles short of a safe landing.

The Longest Leg

Their best option, it seemed, was to fly instead to the Penedo de São Pedro, a set of rocks located in the doldrums of the South Atlantic. There, they would make a landing and put on more fuel from the support ship. Thus, they repositioned to Porto Praia as originally planned — this required a 2 hour and 15 minute flight — which they accomplished on April 17. From this new point farther south, the distance to the rocks was just 908 miles, well within the restricted range of their seaplane. As usual, the NRP República left well ahead of the flight to stand station at the rocks for refueling.

On the appointed day, they took off at 05:55. Just fifteen minutes later, they were out of sight of land. To complete the shorter leg ahead, they had loaded 255 gallons of fuel, giving them a margin of safety with the extra water that was trapped in the two floats. The plane flew noticeably tail-heavy — clearly, more water had seeped in, and the pilot noted that the added weight had shifted the CG rearward. Two hours into the flight, they measured the fuel and realized that they had only enough left to make it 10 hours. Since the fuel burn rate didn’t match the amount of the fuel in the tanks, their best assessment was that some fuel had evaporated overnight after refueling — they had neglected to recheck the fuel load prior to take off.

The winds were not cooperating either. Instead of averaging nearly 80 mph, they were well short of that. Recalculating the distance, they realized that unless they found a reasonable tailwind, they would fall short of the rocks and waiting ship. Should they return to Porto Praia or go on, hoping for better wind?

Reaching the “point of no return”, they had to make a tough call. They decided to press on.