Published on April 4, 2013

The First Air Fleet, the same Japanese Navy unit that had successfully attacked Pearl Harbor, secretly sailed from its base in Japan on another attack mission, this one code-named “Operation C”. The goal of the operation was to head west into the Indian Ocean and destroy the British Eastern Fleet at anchorage in Ceylon. It was a daring move, one which was entirely unexpected and, if successful, would have changed the outcome of the war. It might well have been successful too, if not for several factors, including intercepts of Japanese communications and one man and his flight crew, a Canadian serving with 413 (Canadian) Squadron named Sqn Ldr Leonard Birchall, RCAF, who had just one day earlier arrived after a ten day flight from the Shetland Islands, north of Scotland. For his role that day, April 4, 1942 — today in aviation history — he would be forever after remembered as the “Saviour of Ceylon”.

The Japanese and British Fleets

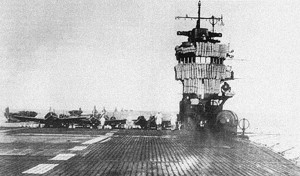

For Operation C, the First Air Fleet consisted five aircraft carriers, the Akagi, Hiryu, Soryu, Shokaku and the Zuikaku. Together, they carried more than 300 aircraft, a force sufficient to create a devastating surprise attack on the scale of another Pearl Harbor. As well, the fleet included four battleships, the Haruna, Hiei, Kirishima and Kongo, and two heavy cruisers, the Chikuma and Tome. Finally, a light cruiser and eight destroyers rounded out the force.

At Ceylon, the British Eastern Fleet had just been constituted, assembled from the remaining forces available after the losses suffered by the Japanese advances in the Pacific. Many older vessels had reinforced from the Atlantic fleet to bolster British naval power in the region. The Royal Navy ships at harbor there included two of the large fleet carriers, the HMS Formidable and HMS Indomitable as well as the smaller aircraft carrier HMS Hermes. These ships fielded only a handful of aircraft, just 80 in total and virtually all outdated designs. The Royal Navy also had deployed the battleships, HMS Ramillies, HMS Resolution, HMS Revenge, HMS Royal Sovereign, and HMS Warspite. As well, two heavy cruisers, the HMS Cornwall and HMS Dorsetshire, and five light cruisers were at anchor along with 14 destroyers.

On first glance, the British Eastern Fleet seemed a sizable force, but the older R-Class battleships were slow and outdated and the aging heavy cruisers were also not up to the standard of the day. Truly, only the two fleet carriers were a serious threat to the Japanese, yet they fielded just 45 Fairey Albacore biplane torpedo bombers, 14 Grumman Martlets (a modified version of the F4F Wildcat), 12 Fairey Fulmar (a two seat fighter) and, best of all perhaps, 9 Hawker Sea Hurricanes. This was further bolstered by RAF forces from Ratmalana Airfield and an improvised strip at a local racetrack. This fielded a total of an additional 42 fighters from 30 Squadron (22 Hawker Hurricanes), 258 Squadron (14 Hawker Hurricanes), and six Fairey Fulmars from the thinly equipped 803 and 806 Squadrons. The approaching Japanese fleet with its 300 aircraft, including the Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters, had a significant qualitative advantage — further, the Japanese Navy pilots were among the most experienced and best in the world.

The Japanese Plan

Overall, the British were in serious trouble in India and Ceylon. The Japanese forces had advanced nearly to India’s border and the CBI theater was under grave threat. The Japanese were helping fund and support a nascent independence movement within India itself — later that movement would culminate in the end of British colonial rule, but that would take place after the end of WWII. This was a shrewd strategy since a newly independent India would withdraw from supporting the Allies and become a neutral country for the remainder of the conflict. If the British Eastern Fleet could be neutralized, the colonial rule of India would be seriously eroded, which would enable and inspire the independence movement, to Japan’s advantage.

Operation C was thus born with a single goal — to attack by air and destroy the British Naval forces in a single day. The Japanese had no interest in invading Ceylon itself, nor occupying any lands in southern India. The attack would have to be a surprise to catch the British unprepared and, as had been achieved just four months before at Pearl Harbor, inflict a crippling blow. If it could be done, the British presence in the Indian Ocean would have been completely annihilated, which would have had grave consequences for the supply of materiel reinforcements to India, Australia, Burma and New Zealand.

413 (Canadian) Squadron

Only a week prior to the Japanese approach against Ceylon, the RCAF’s 413 (Canadian) Squadron had begun arriving from Sullom Voe in the Shetland Islands. From those small islands north of Scotland, they had been flying aerial reconnaissance and counter-submarine support for merchant convoys destined for Murmansk in the Soviet Union. With rapid advances of the Japanese in the Pacific in the first three months after Japan entered the war, 413 Squadron received orders to head to Ceylon as part of an emergency reinforcement program to give the newly formed British Eastern Fleet long range patrol.

413 Squadron was equipped with the American-built Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat, an excellent long range reconnaissance and anti-submarine aircraft. Over the previous months, 413 had done extensive work in the North Sea, searching for German U-Boats and watching out for the German Navy’s few, but highly advanced capital ships which had menaced the Arctic merchant routes. The deployment to Ceylon, however, was a ten day flight that traced its way across northern Africa and through the Middle East, Pakistan, India and finally to Ceylon itself.

The Saviour of Ceylon

Among the pilots of the 413 Sqaudron was the 26 year old Squadron Leader Leonard Joseph Birchall, RCAF, a native of St. Catharines, Ontario. The 413 had only just gotten its first PBY Catalinas to Ceylon when the Japanese fleet was approaching. The first of the 413 pilots to arrive with a Catalina was Flight Lieutenant Rae Thomas, DFC. He arrived at the end of March and flew his first reconnaissance sortie on March 31. Sqn Ldr Birchall was the second pilot to arrive with his aircraft, coming to Ceylon on April 2. He had one day of rest before he was launched to join Flt Lt Thomas in searching the waters for enemy ships. The mission he flew that day was an intensive one — typical Catalina missions were 36 hours long — and Sqn Ldr Birchall was immediately sent out on April 4 — today in aviation history. Responding to his navigator’s request to add an additional southern search line so as to verify their position over the water with a morning celestial position, Sqn Ldr Birchall was shocked to spot a small, distant dot on the horizon yet further south of his plane. He turned to investigate.

As he flew toward the dot, he spotted additional dots nearby. Soon, they were recognizable as a full scale fleet of ships and shortly afterward, they were clearly identifiable as warships. RAF protocol required that messages be encoded and transmitted three times for clarity. He could have turned away at that point and broadcast a coded message that perhaps a dozen or more warships had been sighted at that location, heading toward Ceylon, yet Sqn Ldr Birchall and his crew were not satisfied with that. He intended to gain full knowledge and information of the exact composition of the fleet.

At great risk, Sqn Ldr Birchall made a high speed, low altitude run toward the Japanese fleet, first overflying the destroyers that stood picket watch at the fringes. These reported his presence and opened fire with their anti-aircraft artillery. The Japanese had deployed a combat air patrol of 12 Mitsubishi A6M2 Zeroes that were circling high above the fleet — unbeknownst to him, they were called down to intercept Birchall’s plane and shoot it down. Quickly, the radioman encoded the full report and began to rapidly transmit his warning message.

Shoot Down

As he began, the twelve Zeroes attacked. Despite the Japanese planes, twice Birchall’s radioman got through the coded message with his broadcast. As he began his third transmission, by chance the Zero fighters shot out his radio, wounding him in the process. Whereas Sqn Ldr Birchall had managed to dodge the intensive AAA barrage, the fighters were another thing altogether. They were faster, more maneuverable, better armed and had an altitude advantage. In a PBY Catalina, Birchall and his crew were practically indefensible and only able to fly at 150 kts. Predictably, the attack by the Zeroes did massive damage to the plane. Barely under control, Birchall managed to do an emergency landing at sea before the tail fell off his plane. Since the Catalina was a flying boat, it wasn’t quite classified as a ditching, but that was mere semantics — it may as well have been given the violence of the situation and condition of the plane.

The flight crew clambered into a raft and rowed away from the rapidly sinking airplane as the twelve Zeroes strafed the wreckage — in these attacks, two of the eight man crew were killed. It wasn’t long before a Japanese destroyer picked up the remain six survivors. Once transferred to another ship for interrogation, Birchall’s crew claimed that they had been shot down before transmitting a message. Further, they crew maintained that they had just arrived at Ceylon the day before from the North Sea assignment — a fact that the Japanese intelligence officers were able to later confirm — and thus knew nothing of the British strength on the island.

The Defense of Ceylon

The Japanese attack on Ceylon was launched on the following morning on April 5, 1942 — it was Easter Sunday. Though they had intercepted a message from Colombo asking Sqn Ldr Birchall to repeat his message with the third confirmation — thus concluding that the Canadians had indeed made a report — the Japanese still felt that they could achieve tactical surprise. The leader of the Japanese attack was none other than Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who no doubt expected the engagement to follow along the lines of his experiences at Pearl Harbor. Based both on SIGINT intercepts relayed from American codebreakers and Birchall’s report, the British Eastern Fleet had been repositioned southward to a secret anchorage site at Addu Atoll, afterward deploying to sea in hopes of engaging the Japanese in a night battle — ultimately, that was not to be. Almost two dozen merchant ships and a couple of destroyers and other smaller warships remained at harbor at Colombo, largely because they were unserviceable for seagoing operations at the time.

As the Japanese aircraft approached that morning for what they would be an Easter surprise, at least some of the Royal Air Force aircraft were already launched. Despite the ample warnings they had, many were still on the ground at the time of the attack. The violent air combat that followed involved a disorganized attack on the Japanese formation. Nearly half the British fighters were shot down, but they managed to inflict some losses on the Japanese as well. Yet the surprise attack had been disrupted and the damage done was not as much as it might have been. The Japanese air fleet returned to its aircraft carriers, realizing that the attack on Colombo’s harbor was a failure — the British Eastern Fleet was largely missing. As well, two dozen other merchant vessels had heeded Birchall’s warning and fled the harbor.

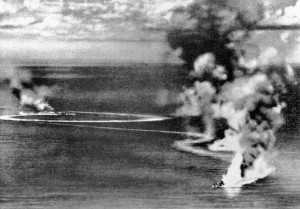

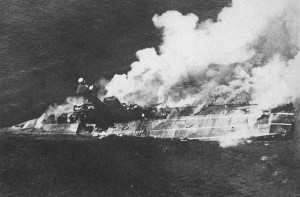

A few hours later, reconnaissance planes from the IJN ship Tome spotted the British Eastern Fleet’s two heavy cruisers, the HMS Cornwall and HMS Dorsetshire. A follow-up air attack sank both, at great loss of life. The Japanese returned again on April 9 to bomb Trincolmalee harbor in Ceylon. Once again, they swept about half of the defending RAF planes. Further, Japanese scout planes located the HMS Hermes and her escorts, even if she was at sea. An attack by Val dive bombers sank the carrier. Despite the overall successes (in raw terms, one carrier, two heavy cruisers, two destroyers, a corvette, and five merchant and support, plus 45 RAF fighter aircraft that had defended the island, as seen against the loss of 17 Japanese aircraft), the goal of annihilating the British Eastern Fleet had not been achieved. Most importantly, the two fleet carriers were still at large. The Japanese withdrew and returned to their home port.

Aftermath

After their capture , Birchall and his men would spend the rest of the war in a Japanese prison camp, enduring horrific conditions. Nonetheless, Sqn Ldr Birchall would stand up to the Japanese brutality, over and over intervening to protect men under torture and demand better treatment. Routinely, he was severely beaten, yet his example and steadfast commitment to never give in to the Japanese inspired many of the other prisoners and his reputation spread from camp to camp, inspiring others to follow his example.

After the war, Sqn Ldr Birchall, later promoted to Air Commodore, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions that day in locating and reporting the composition of the Japanese fleet. As well, he was invited to the membership of the Order of the British Empire for his actions while held as a prisoner of war. Above all, however, were two honors that he would carry for the rest of his life — first, he was declared the “Saviour of Ceylon” for having foiled the Japanese surprise attack, though that was a bit of an overstatement perhaps given the actual outcome; and second, he was honored by none other than Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, who wrote that Birchall and his crew were responsible for “one of the most important single contributions to victory.”

As for the defense of Ceylon, Churchill also stated, “”The most dangerous moment of the War, and the one which caused me the greatest alarm, was when the Japanese Fleet was heading for Ceylon and the naval base there. The capture of Ceylon, the consequent control of the Indian Ocean, and the possibility at the same time of a German conquest of Egypt would have closed the ring and the future would have been black.”

Ultimately, Sqn Ldr Birchall’s efforts at Ceylon were extraordinary. Mistakes were still made and the Japanese still achieved some level of surprise, but his reports had confirmed the actual numbers of attacking aircraft carriers and the British had made enough preparations to achieve the key goal — ensuring that the British Eastern Fleet was kept safe from the attack itself. That was, above all, the greatest victory.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Commander Mitsuo Fuchida lead the attack on Pearl Harbor and on Ceylon. What became of him during the war?

You state that Squadron Leader Birchall’s Radio Signal described the EXACT composition of the Nagumo Task Force, including the five aircraft carriers, when it was transmitted, Could you kindly tell me where an exact copy of this Radio Transmission, as sent or as received, is held which gives this detail, so that I might view it please? I have been unable to trace it anywhere in the UK archives.

Peter C Smith

Peter, slightly different versions of Birchall’s signal appear in British records:

At 1629 on 4 April Colombo W/T sent following MOST IMMEDIATE signal to call sign MXW [All British Men of War]:

“Catalina patrol reports large enemy force 155 degrees [from] Dondra Head 360 miles at 1005Z 4th course 330 degs.”

At 2019 Colombo W/T sent a follow-up message which said that the above signal “was a paraphrased version of T.O.O. [Time of Origin] 1005/4 which was corrupt received 6666 from Catalina A/C.”. I don’t know what “6666” means.

The ORB for the flying boat station at Koggala records the signal as follows:

“Large enemy force 5 miles ———–

3 – 15 – 330 – 00040’N 83010’E. T.O.O 10.05”

Rob Stuart

My father, Cpl. Lloyd T. Sawyer, was part of Leonard Birchall’s aircrew. The day Birchall and his crew were shot down, my father was told by Birchall to remain behind as it was a short mission and he would not be taking a full crew that day. In my father’s war diary, he made note of the missing seven crew members by name and mentioned that he lost his overalls and jackknife on the missing plane. My father and Air Commodore Birchall were finally reunited 43 years later, almost to the day, in Delta, Ontario, Canada.