Published on May 13, 2013

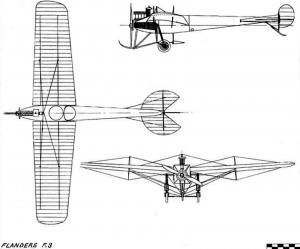

One hundred and one years ago today in aviation history, on Monday, May 13, 1912, there was a terrible accident at Brooklands. Two men, the pilot, Edward Victor Beauchamp “E. V. B.” Fisher, and his passenger, Victor Mason, an American, were killed. The plane, a Flanders F.3, crashed into the ground and burst into flames. Just what had caused the accident was unclear, despite that the fiery end was witnessed by over 200 people. Faced with a mystery, the Royal Aero Club took the opportunity to undertake a formal investigation. What followed was the first aviation accident investigation in history.

Despite the crude nature of aircraft at the time and primitive state of aviation technology, the native professionalism of the British called for a report of the highest standards. The format, quality, and depth of research involved in preparing the report quickly established the world standard for all future aviation accident reports, not just in Britain but around the world. Therefore, in honor of the efforts made all those years ago, we hereby republish what amounts to Accident Report No. 1.

Though outtakes have been republished before, we present the full findings — all 13 points, a rather unlucky number…. And remember, the report was intended to establish a methodology to enable manufacturers, maintenance personnel, support personnel, and the aviators themselves to learn from what mistakes were made and to help ensure a safer future.

The Report — from Flight, June 8, 1912

BROOKLANDS ACCIDENT.

Report on the fatal accident to Mr. E. V. B. Fisher and his passenger, Mr. Victor Mason, when flying at Brooklands on Monday, May 13th, 1912, at about 6 p.m.

Brief Description of the Accident. — Mr. E. V. B. Fisher flying with a passenger on a Flanders monoplane fitted with a 60-h.p. Green engine had made two or three circuits of the Brooklands flying ground. He was making a left-hand turn when the aircraft fell to the ground, killing both the aviator and passenger. Almost immediately after contact with the ground, the aircraft was in flames.

Report. — The Special Committee sat on the following dates: — Tuesday, May 21st, Wednesday, May 22nd, and Tuesday, May 28th, 1912, and heard the evidence of two eye witnesses, both of whom were aviators holding certificates. The Committee also heard the evidence of the designer and manufacturer of the aircraft, and of the representative of the maker of the motor. The written reports of other witnesses, and the report of Dr. Eric Gardner, were also considered.

From the consideration of this evidence the Committee is of opinion that the following facts are clearly established: —

(1) That the accident originated while the aircraft was making a left-hand turn at about 100 feet from the ground. (Evidence as to height, in the opinion of the Committee, is not conclusive.)

(2) That the aircraft had turned through an angle of about 90° in the horizontal plane.

(3) That it then side-slipped inwards.

(4) That it struck the ground head first, with the tail practically vertical.

(5 ) That from the effect produced on the engine and other part * the velocity at the moment of striking the ground was very considerable.

(6 ) That the fire which took place originated subsequently to the fall, and was the result not the cause of the accident.

(7) That there is no reason to suppose that the structural failure of any part of the aircraft was the cause of the accident.

(8) That from the commencement of the flight the aircraft was flying tail down.

(9) That the engine was actually running when the aircraft struck the ground.

(10) That Mr. Fisher was not in any way incapacitated so far as the normal control of the aircraft was concerned by an injury to his left shoulder, which he had sustained on April 18th, 1912.

(11) That the passenger did not cause the accident.

(12) That Mr. Fisher was thrown, fell, or jumped out of the aircraft when the latter was a considerable height from the ground, his body being found about 60 ft. in front of the spot where the aircraft struck. The passenger remained in the aircraft: his position was such that he could not readily have been thrown out.

(13) Mr. Fisher was granted his Aviator’s Certificate No. 77, on May 2nd, 1911, by the Royal Aero Club.

Opinion. — The Committee is of opinion that the cause of the accident was the aviator himself, who failed sufficiently to appreciate the dangerous conditions under which he was making the turn, when the aircraft was flying tail down, and in addition was not flying in a proper manner.

A side slip occurred, and Mr. Fisher lost control of the aircraft.

It seems probable that his losing control was caused by his being thrown forward on to the elevating gear, thereby moving this forward involuntarily, which would have had the effect of still further turning the aircraft down. This would explain his being thrown out whilst in the air.

In the opinion of the Committee it is possible that if the aviator had been suitably strapped into his seat he might have retained control of the aircraft.

It was unanimously resolved that this Report be forwarded to the Committee with a recommendation that it be published in extenso.

Comments

In the annals of early aviation, accidents and incidents were all too common. Many early aviators lost their lives. Sometimes they perished while attempting to set new records for distance or altitude. Sometimes the accidents took place while crossing lakes and the sea — or even the English Channel. However, sometimes accidents seemed to be just a matter of bad luck, such as when an engine malfunctioned in flight. Additionally, bad fuel, improper oil weights, and other factors always seemed to be conspiring against pilots and the goal of safe flight.

When E. V. B. Fisher and Victor Mason died, their accident was selected for the first report because it was something of a mystery. They had been flying on a good day, at a reasonable altitude, and just around the airfield. Suddenly, their plane seemed to have just fallen out of control to crash vertically into the ground. The Royal Aero Club’s decision to undertake an investigation was welcomed as a result. Many of the other pilots wondered what had happened. Fisher was just 24 years old and was an able pilot. It made no sense. The story of what happened, it seemed to most, had been buried with his body at the Weybridge Cemetery in Surrey, England.

On May 18, 1912, on the first page of its newsletter, the RAeC published the following, which signaled their interest in undertaking investigations:

Readers of FLIGHT will have gathered from the official notices appearing in its columns of that the Royal Aero Club is keenly appreciative of the need that exists for the thorough and systematic investigation of all flying accidents which are of at all a serious nature. To that end has been established a Public Safety and Accidents Investigation Committee — the title is rather a cumbrous one, perhaps, but it is its work rather than its name which matters…..

Analysis

Incredibly, from the first, the RAeC applied what would later be recognized as required, standard methods. They held inquiries over multiple days, consulted with both the aircraft and engine manufacturer to check for defects in design or materials, they searched for other flaws in the aircraft itself, they consulted with eyewitnesses to determine the events with some detail, and so forth. Implicitly, they put more weight on the opinions of those who were certificated pilots. They even consulted with the doctor who had examined the bodies, looking for any evidence of a medical condition that might have contributed to the accident.

The findings were numbered, discussed in detail, and approved through a formal committee. What was decided was written succinctly and with clarity, and then published for wide review and challenge. The accident investigation and results were extraordinary work.

Sadly, in the end, the RAeC put it down to “pilot error”. A new term was created — and it has been used many times since.

One More Bit of Aviation History

On May 10, 1912, an airman in France succeeded in winning the Claudel Prize. Thankfully, the prize is now longer offered, but it was fitting for the day. The award was reported in the May 11, 1912, issue of Flight, which was the official newsletter of the Royal Aero Club. It read:

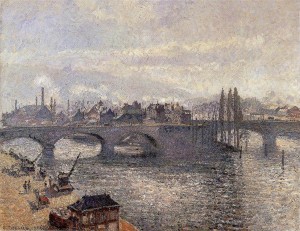

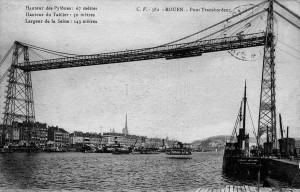

Flying Under and Over a Bridge.

AMONG a number of £40 prizes offered two years ago by the Ligue Nationale Aerienne, was one known as the Claudel Prize, to be given to the first aviator who should succeed in flying over and then under the Corneille Suspension Bridge at Rouen. The feat was accomplished on Sunday afternoon by Cavelier on a Deperdussin monoplane. He started from the Bruyeres Aerodrome, flew over the bridge at a good height, and then turning swooped down and passed under it, afterwards returning to his starting point.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What was Accident Report No. 2?